Land from masanobu hiraoka on Vimeo.

Month: November 2013

A Speech That Defined America – For Good And Ill

Richard Gamble rethinks Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, describing it as when “the wartime president fused his epoch’s most powerful and disruptive tendencies—nationalism, democratism, and German idealism—into a civil religion indebted to the language of Christianity but devoid of its content”:

For anyone who does not already know something specific about the Civil War, the speech creates no picture in the mind. It could be adapted to almost any battlefield in any war for “freedom” in the 19th century or thereafter. Perhaps the speech’s vacancies account for its longevity and proven usefulness beyond 1863—even beyond America’s borders. Lincoln’s speech can be interpreted as a highly compressed Periclean funeral oration, as Garry Wills showed definitively in his 1992 book Lincoln at Gettysburg. But unlike Pericles’ performance, this speech names no Athens, no Sparta, no actual time, place, people, or circumstances at all.

Into this empty vessel Lincoln poured the 19th-century’s potent ideologies of nationalism, democratism, and romantic idealism. Together, these movements have become inseparable from the modern American self-understanding. They have become part of our civil religion and what we likewise ought to call our “civil history” and “civil philosophy”—that is, religion, history, and philosophy pursued not for their own sake, not for the truth, but deployed as instruments of government to tell useful stories about a people and their identity and mission.

Gamble goes on to argue that all this amounted to redefining America, as Lincoln put in his speech, as a nation dedicated to a “proposition” – that all men were created equal – and that this proved problematic:

Embedded in the Gettysburg Address, the proposition defined the making of America and why it fought a costly war. We cannot know how Lincoln would have wielded the proposition in pursuit of America’s postwar domestic and foreign policy; his death in 1865 left that question open, as Republicans and even Democrats used the martyred president and his words to endorse everything from limited government to consolidated power, from anti-imperialism to overseas expansion. Under all this confusion, however, Lincoln’s propositional nation helped move America from the old exceptionalism to the new. He helped America become less like itself and more like the emerging European nation-states of mid-century, each pursuing its God-given benevolent mission.

A propositional nation like Lincoln’s is “teleocratic,” in philosopher Michael Oakeshott’s use of the word, as distinct from “nomocratic.” That is, it governs itself by the never-ending pursuit of an abstract “idea” rather than by a regime of law that allows individuals and local communities to live ordinary lives and to find their highest calling in causes other than the nation-state. Lincoln left all Americans, North and South, with a purpose-driven nation.

But, at the time, not everyone understood the greatness of the speech. The Patriot-News printed this correction last week:

In the editorial about President Abraham Lincoln’s speech delivered Nov. 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, the Patriot & Union failed to recognize its momentous importance, timeless eloquence, and lasting significance. The Patriot-News regrets the error.

You can read Lincoln’s speech here.

The View From Your Window

Afraid To Be Healed

Dreher, reaching the end of Dante’s Purgatorio, is moved by what awaits the poet at the summit of the Mount of Purgatory – Beatrice in the Garden of Eden:

Dante saw the light of God in Beatrice, but by his own weakness, lost that vision, and fell into darkness and despair. We learn here that it took many tears and prayers of Beatrice in heaven, as well as the devotion of Virgil, to get Dante to the top of that mountain. As he told the shades in Purgatory, “I climb from here no longer to be blind.” He desires to see. When Beatrice asks him why he “condescended” to approach joy, she means that everlasting joy only comes to those who sacrifice their all-too-human pride humble themselves in profound repentance, so that they can at last see God, or to put it in more theological terms, attain the Beatific Vision.

I am thinking of the incident in the Gospel of John, Chapter 5, in which Jesus approaches the chronically ill man at the Bethesda pool. He asks the man, “Do you want to be healed?” It’s a strange thing to ask; of course the man wants to be healed, right? But on second thought, it is by no means clear that we really want to be healed. Many of us think we want to be healed of our afflictions — I’m speaking in the spiritual sense here — but the truth is, we have made icons of our passions, and even our brokenness, and are frightened by the prospect of life without them. The sicker we are, the stronger the medicine to restore us must be. Dante is not sentimental about this. We face an arduous climb to overcome ourselves and our passions. Longing for Divine Grace — in the Divine Comedy, represented by the figure of Beatrice — propels us forward; note that in Purgatory, we can only move as fast as we desire to move. God, in His infinite love for us, will not compel us to come to him. We have free will. We have to have within our own breasts the desire to see ourselves as we really are, and God as He really is, so that we can at last renounce that which separates us from Him.

We must climb so that we will no longer be blind.

Tweet Of The Day

If you like your Doctor, you can’t keep him – the BBC casts a new actor every four years.

— Eric Kleefeld (@EricKleefeld) November 14, 2013

Heh.

Hang In

Sorry for the slow load-time today. We’re working on it.

Quote For The Day

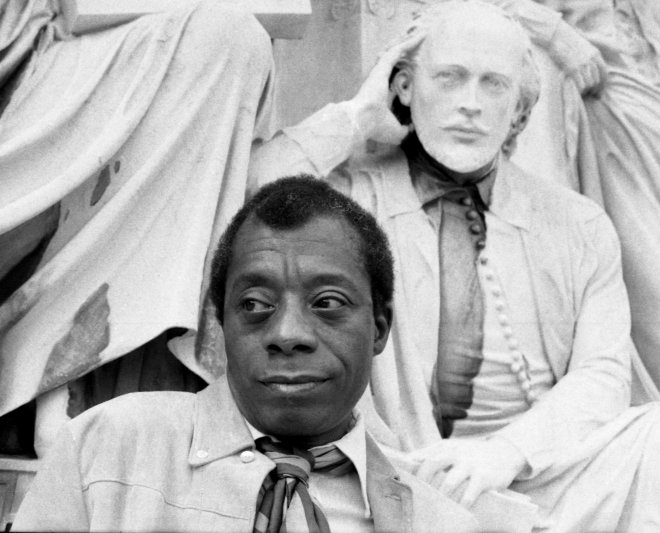

“About my interests: I don’t know if I have any, unless the morbid desire to own a sixteen-millimeter camera and make experimental movies can be so classified. Otherwise, I love to eat and drink — it’s my melancholy conviction that I’ve scarcely ever had enough to eat (this is because it’s impossible to eat enough if you’re worried about the next meal) — and I love to argue with people who do not disagree with me too profoundly, and I love to laugh. I do not like bohemia, or bohemians, I do not like people whose principal aim is pleasure, and I do not like people who are earnest about anything. I don’t like people who like me because I’m a Negro; neither do I like people who find in the same accident grounds for contempt. I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually. I think all theories are suspect, that the finest principles may have to be modified, or may even be pulverized by the demands of life, and that one must find, therefore, one’s own moral center and move through the world hoping that this center will guide one aright. I consider that I have many responsibilities, but none greater than this: to last, as Hemingway says, and get my work done. I want to be an honest man and a good writer,” – James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son.

(Portrait of Baldwin in 1969 by Allan Warren via Wikimedia Commons)

Why Faith Has No Formula

Wittgenstein once wrote that “Christianity is not a doctrine, not, I mean, a theory about what has happened and will happen to the human soul, but a description of something that actually takes place in human life.” Reviewing Nathan Schneider’s God in Proof, Robert Bolger believes the statement captures how arguments for the divine actually function:

Assenting to a proof for God is similar; it is couched in the language of rationality — it argues for the existence of something. Yet, as I hint at in my own book, Kneeling at the Altar of Science, the impetus behind accepting a religious proof as valid comes from a person’s gut (or soul) and not merely from her mind. The proofs are only meaningful for certain people; whether they mean anything has more to do with what we bring to the proofs rather than what the proofs brings to us. Isn’t this odd? It certainly is because it is odd to say that proofs “prove” only if we are in a position to see them as proofs. But the oddity disappears when we realize that this is actually what we mean by “proof” in a religious context. Schneider writes, “Assent, like this, is a convergence — a meeting of circumstances, choices, and the best of one’s knowledge.”

What the book might teach us about the search for God:

[T]his leads to another radical claim, namely, that the truth of a religious proof cannot be known except by those who accept it. This is an important point to make since it lets us see that searching for God is not simply searching for some thing among others, a being among other beings, or a creature that is strong and powerful but lives far away. If God could be found at the end of a logical proof, then finding God would be like finding a solution to a math problem or surmising a previously unknown planet by the laws of physics. It is only in the failure of the religious proofs to function in the way other proofs do that we learn something about the meaning of the word “God.”

A Poem For Sunday

“I Dreamed I Met William Burroughs” by Franz Wright:

I met William Burroughs in a dream.

It was some sort of bohemian farmhouse,

and he was enthroned, small and skeletal,

in a truly gigantic red armchair.When I asked him how he was, he replied,

Well, you know what they say—for best results

always mock and frighten lobster before boiling.

Franz—I like that name, Franz. Childe Franzto the dark tower something or other . . . Hey,

got a smoke? And quit worrying so much:

they can’t help themselves, they’re like abused dogs

and they’re going to react to affection and kindnesswith uncontrollable savagery. Just tell them,

You’re out of my mind, pal. You’re out

of my mind. Either that or, I’m out of yours.

That’ll keep them brain-chained to their trees.

(From F/poems © 2013 by Franz Wright. Reprinted by kind permission of Alfred A. Knopf. Image of Burroughs by Christiaan Tonnis, via Wikimedia Commons)

Breaking Faith In Science

Jerry Coyne rejects the arguments of those “who claim that science and religion are compatible” because, supposedly, “science, like religion, rests on faith: faith in the accuracy of what we observe, in the laws of nature, or in the value of reason.” Not so fast, he says:

The conflation of faith as “unevidenced belief” with faith as “justified confidence” is simply a word trick used to buttress religion. In fact, you’ll never hear a scientist saying, “I have faith in evolution” or “I have faith in electrons.” Not only is such language alien to us, but we know full well how those words can be misused in the name of religion.

What about the public and other scientists’ respect for authority? Isn’t that a kind of faith? Not really. When Richard Dawkins talks or writes about evolution, or Lisa Randall about physics, scientists in other fields—and the public—have confidence that they’re right. But that, too, is based on the doubt and criticism inherent in science (but not religion): the understanding that their expertise has been continuously vetted by other biologists or physicists. In contrast, a priest’s claims about God are no more demonstrable than anyone else’s. We know no more now about the divine than we did 1,000 years ago.

Why scientists don’t have “faith” in the laws of nature or in reason:

The orderliness of nature—the set of so-called natural laws—is not an assumption but an observation. It is logically possible that the speed of light could vary from place to place, and while we’d have to adjust our theories to account for that, or dispense with certain theories altogether, it wouldn’t be a disaster. Other natural laws, such as the relative masses of neutrons and protons, probably can’t be violated in our universe. We wouldn’t be here to observe them if they were—our bodies depend on regularities of chemistry and physics. We take nature as we find it, and sometimes it behaves predictably.

What about faith in reason? Wrong again. Reason—the habit of being critical, logical, and of learning from experience—is not an a priori assumption but a tool that’s been shown to work. It’s what produced antibiotics, computers, and our ability to sequence DNA. We don’t have faith in reason; we use reason because, unlike revelation, it produces results and understanding. Even discussing why we should use reason employs reason!