Neetzan Zimmerman, the master of viral content, makes an astute observation:

I’d argue that most viral content demands from its audience a certain suspension of disbelief. The fact is that viral content warehouses like BuzzFeed trade in unverifiable schmaltz exactly because that is the kind of content that goes viral. People don’t look to these stories for hard facts and shoe-leather reporting. They look to them for fleeting instances of joy or comfort. That is the part they play in the Internet news hole. Overthinking Internet ephemera is a great way to kill its viral potential.

In response, Felix Salmon observes that there’s “now so much fake content out there, much of it expertly engineered to go viral, that the probability of any given piece of viral content being fake has now become pretty high”:

If your company was built from day one to produce stuff which people want to share, then that will always end up including certain things which aren’t true. That’s not a problem if you’re ViralNova, whose About page says “We aren’t a news source, we aren’t professional journalists, and we don’t care.” But it becomes a problem if you put yourself forward as practitioners of responsible journalism, as BuzzFeed does.

It has become abundantly clear over the course of 2013 that if you want to keep up in the traffic wars, you need to have viral content. News organizations want to keep up in the traffic wars, and so it behooves them to create viral content — Know More is a really good example. But the easiest and most infectious way to get enormous amounts of traffic is to simply share the stuff which is going to get shared anyway by other sites. Some of that content will bear close relation to real facts in the world; other posts won’t. And there are going to be strong financial pressures not to let that fact bother you very much.

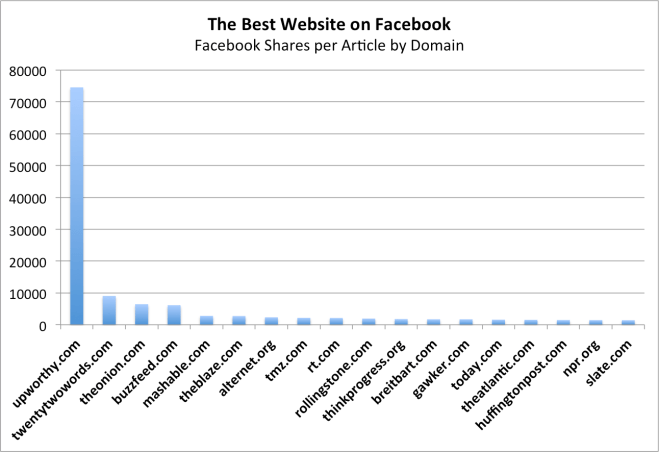

Derek Thompson passes along the above chart on viral traffic:

The most impressive thing about Upworthy is that it publishes just 225 articles a month, according to this data. That’s one for every 508 articles on Yahoo! The site is so much more dominant than other news sites on Facebook that when you graph its Facebook-shares-per-article, it looks like a skyscraper dropped into a desert. Upworthy averages about 75,000 Facebook likes per article, 12x more than BuzzFeed.

Ezra Klein ponders this fact:

The question Upworthy’s success raises is whether there are negative returns to posting so much content. Perhaps the time spent producing thousands of articles, most of which have very slight readership, would be better spent producing hundreds of articles more thoughtfully because more will go wildly viral. Lower content expectations give writers more time to find amazing stories, to get amazing quotes, to come up with amazing headlines.

Or so goes the theory. Certainly a lot of writers would like to believe that. But what Upworthy is doing isn’t giving writers a lot of time to create content that may or may not cohere into something that could go viral. They’re giving writers a lot of time to find content that they’re pretty sure will go viral. If you want to find something that will go nuts on Facebook, time spent sorting through what already exists is likely a lot more efficient than time spent creating something from scratch. It’s entirely possible that if a place like The Post attempted to ratchet back on content expectations they would end up both with less content and less virality.

Drum notes that Upworthy’s much remarked upon headlines are often misleading:

Upworthy’s headline-writing black magic has become endlessly talked about as the apotheosis of our modern, millennial, warp-speed, social-media driven culture. But you know what it reminds me of? Supermarket tabloids.

The supermarket tabs aren’t what they used to be, but back in their heyday this was their meat and drink. Every issue featured half a dozen titillating headlines on the cover that sucked you into a story on page 24 that was….usually kind of meh. They did their best to hide this, of course, but most of the time their headlines turned out to be come-ons that ultimately ended in disappointment. Still, you never knew if the next one might be the real deal. Hope springs eternal, so you kept coming back for more.

Other things in the same category: The New York Post. Modern movie trailers. Ron Popeil infomercials. British tabloids. Porn spam. TED talks.

Yglesias zooms out:

From a business viewpoint, I think an important point to make about this is that “viral” basically just means “is popular on Facebook” since Facebook is really the only host for viral content that matters. And that in turn means that all the viral traffic a website gets is really Facebook‘s traffic. It’s been clear for a long time now—like going back to well before there was an Internet—that journalism just isn’t that popular. Most households in the New York City metro area never subscribed to the New York Times, for example. Facebook, by contrast, is something that people really like. So since Facebook is so much more popular than journalism, it turns out that the most popular kind of journalism is Facebook content.

But this is still really Facebook’s traffic. Not just in the sense that Facebook can always tweak the algorithms that determine what plays well on Facebook, but in the sense that whatever economic value is created by “viral” content will ultimately be captured by Facebook. If you want to advertise to an audience of people eager to consume Facebook-friendly content, after all, the logical place to do that is on Facebook.