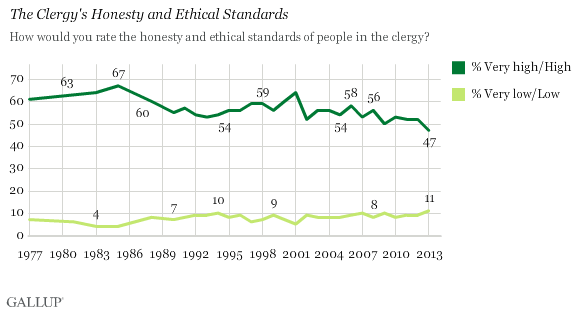

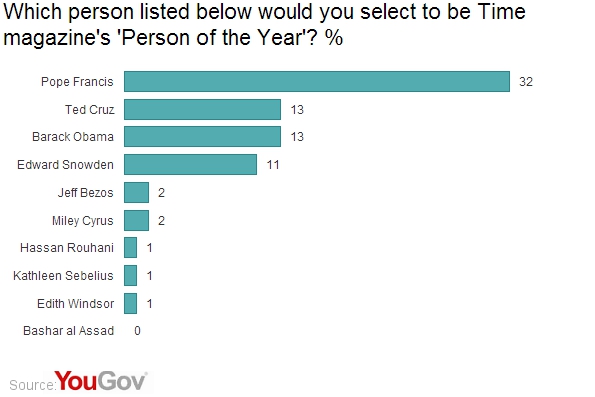

Americans agree with Time:

Even The Advocate named Francis as their person of the year:

As pope, he has not yet said the Catholic Church supports civil unions. But what Francis does say about LGBT people has already caused reflection and consternation within his church. The moment that grabbed headlines was during a flight from Brazil to Rome. When asked about gay priests, Pope Francis told reporters, according to a translation from Italian, “If someone is gay and seeks the Lord with good will, who am I to judge?”

The brevity of that statement and the outsized attention it got immediately are evidence of the pope’s sway. His posing a simple question with very Christian roots, when uttered in this context by this man, “Who am I to judge?” became a signal to Catholics and the world that the new pope is not like the old pope.

Sean Bugg dissents, while I simply reel at the gay community’s embrace of a Pope. I mean: 2013 was a huge year for marriage equality – but also for gay-Catholic relations? What have I, what have I, what have I done to deserve this? Candida Moss is another Doubting Thomas:

[W]e have yet to see the kinds of doctrinal tinkering the media has attributed to him.

When it comes to the hot-button cultural issues that animate the Rush Limbaughs of the world, nothing has changed. Francis has been clear that the church’s position on abortion is not up for discussion, and he recently excommunicated Father Greg Reynolds of Melbourne, Australia, presumably for officiating at unsanctioned gay marriages. This pope may be extraordinarily compassionate, but he still enforces church order.

Damon Linker makes similar points:

Unlike his predecessors, Francis holds an apparently sincere belief in dialogue, bridge-building, conciliation, and the adjudication of differences. It seems important to him to appear cheery, tolerant, cosmopolitan. He has made respectful, open-minded statements about the members and beliefs of other Christian churches, as well as about Jews, Muslims, and even atheists.

But in every case where Francis has reached out to those who disagree with him, he has done so while indicating that his own beliefs grow out of Catholic bedrock. In the same airborne news conference during which he made headlines for seeming to counsel against damning gay priests, he responded dismissively to a question about women’s ordination, stating bluntly, “That door is closed.”

But Linker ends up softening his argument somewhat:

Even as Francis’s gestures make headlines, the Church does not think in terms of news cycles or election cycles, but rather in terms of centuries. A new Pope appoints the bishops, archbishops, and cardinals who will govern the Church of the future and in turn elect the next Pope, who will then make his own appointments, and so on, down through the decades. It may seem crazy to progressive Catholics that they’ll likely have to wait another 100 years for their Church to declare the use of condoms to be morally licit or to permit a woman to celebrate Mass. But something has to set the wheels of change in motion, and that just might be the modest but vital reform that Pope Francis ends up being remembered for most of all.

I think Damon is wrong about contraception. The highest authorities in the church argued exactly that almost fifty years ago – that condoms and the pill were licit. It was an over-reaching papacy that quashed it unilaterally. And undoing that over-reach is arguably the core goal of Francis’ pontificate.