This Gentoo #Penguin just ate our @GoPro. #Antarctica pic.twitter.com/C3WiODL43O

— M/S Expedition (@g_msexpedition) December 2, 2013

Month: December 2013

The Pull Of The Cigarette, Ctd

Spurred by this post, a reader shares a curious connection:

In 2000, I quit my pack-and-a-half-a-day habit. In 2004, I was knocked to my knees by a sudden onset of ulcerative colitis, a particularly sanguinary bowel condition that, at its peak, involved up to 20 trips to the bathroom a day and the occasional change of underwear. The very expensive medication I was given seemed to be doing the trick and the tumult in my gut stabilized to normalcy. I also started smoking again.

Last year I decided to quit smoking again, as a gift to myself and to my girlfriend. Within a month – and after 8 years of remission – the colitis returned, as bloody and disruptive as ever. I went to see a gastroenterologist and, during the course of the appointment, off-handedly remarked that I had quit smoking. He looked at me and said, “Oh. That’s why your colitis is back.”

We tried medication, gradually escalating it with my UC only getting worse, until it was time to start using steroids. I did not want to do this. I had visions of the swollen Jerry Lewis from when he was on steroid treatment. And there was no guarantee that it would work.

I tried using nicotine patches. No effect. Finally, with my quality of life having deteriorated substantially (imagine being seized with emergency-level bloody diarrhea at least once an hour), about a year ago I gave in and bought a pack of cigarettes. Within a week the colitis was gone.

I now wear a nicotine patch to help keep the number of cigarettes I smoke daily down to about 10. My doctor never encouraged me to smoke again, but he didn’t give me any grief about it, either. To my knowledge, the medical community has not figured out why smoking puts UC into remission, nor why quitting smoking so often causes UC. But there it is. I smoke for my health.

Getting Away With It

Ever break the law? A Minnesota attorney is soliciting confessions:

[Emily] Baxter’s new project “We Are All Criminals” examines the illegal activities committed by people without a criminal record. In Minnesota, one out of four residents has a criminal record, but Baxter’s project, she says on her website, is about the 75 percent that “got away, and how very different their lives may have been had they been caught.” By emphasizing the crimes of the unconvicted, Baxter blurs the lines between criminal and noncriminal and draws attention to the detrimental effects that a criminal record has on the lives of those who are convicted. Many of the undocumented and unpunished transgressions confessed through her project were committed when the perpetrators were juveniles, many of whom are now lawyers, doctors, and professionals.

The above photo comes from a comic-book store manager who swiped a full-sized Dalek replica and sold it for $3,000 on eBay. Read his story here.

The Pope And The American Right, Ctd

Patrick J Deneen’s piece is very helpful. Money quote:

I think it is because of the left’s “narrative of disruption” [about Francis] that the right is panicked over Francis’s critiques of capitalism. These Vatican criticisms—suddenly salient in ways they weren’t when uttered by JPII and Benedict—need to be nipped in the bud before they do any damage.

The American right has gotten used to believing that Catholicism is cool because of its teachings on sex, abortion, homosexuality, marriage and contraception. And that has been a core feature of the theocon-neocon popular front this past decade or two. But it has always relied on ignoring or suppressing the critique of market capitalism that has long been embedded in Catholic social thought and was enunciated by John Paul II and Benedict XVI repeatedly. Just as the church challenges the left on some social issues, it deeply challenges the right on economic ones. I think it’s healthy that the right is now turning on this Pope. Catholicism is deeper, broader and more complex than any right or left political co-optation would have you believe.

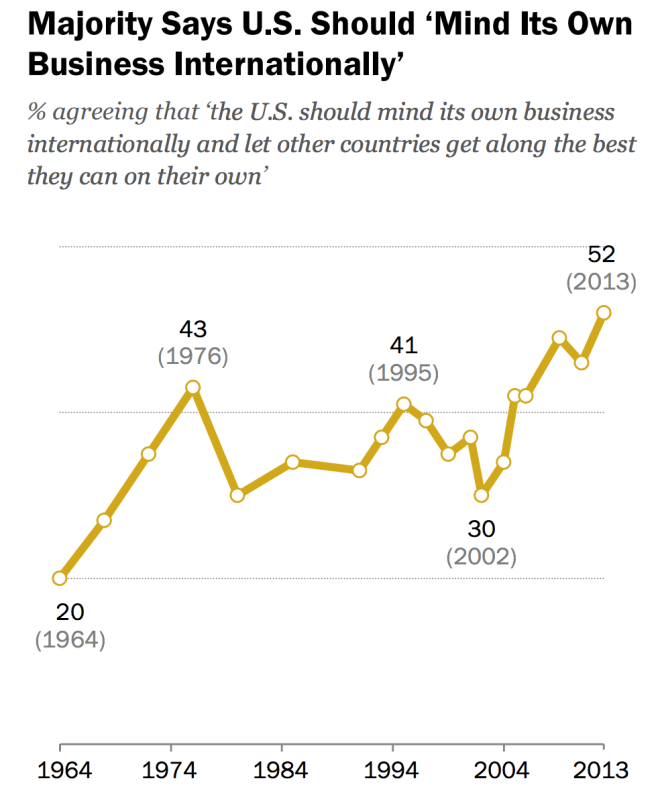

The Role Americans Want America To Play

Drezner flags a new Pew survey (pdf) on foreign policy. He notes that historically, “there’s a foreign policy disconnect between Washington elites and the rest of the country — the former is far more enthusiastic about liberal internationalism than the latter.” But that is less true today:

What’s driving this convergence of views? I’d suggest that the hangover of Iraq, the curdling of the Arab Spring, the Great Recession, and the evaporation of the neoconservative wing of the GOP foreign policy apparatus all have something to do with it (see here for more). Furthermore, in policy terms the convergence has been even more concentrated: President’s Obama’s policies towards Syria and Iran mirror public attitudes much more closely than elite attitudes.

Mataconis notes that Americans are becoming warier of US intervention around the world:

The public, it seems, is tired of war and tired of the United States must involve itself in every potential conflict around the globe. At the same time, though, it would be unfair to label the public’s attitude as “isolationist” when, at the same time, they are strongly in favor of the nation’s role in the global economy and in favor of seeing that type of international engagement expanded in the future. …

Perhaps the most interesting takeaway from the poll, though, is found in the fact that increasing numbers of the American public sees the U.S. as playing a lesser role in the role in the world today than it has in the past, and that it has lost respect in the world over the years, and they seem entirely okay with that. Does this mean that the jingoistic vision that once motivated American foreign policy in both parties, and which seems to still be a strong part of foreign policy in the Republican Party is fading away? Or, is it a reflection of a general pessimism about the direction the nation has been moving in the past decade or so?

Robert Golan-Vilella adds his analysis:

The main headline that some observers have grabbed on to in the Pew poll is that the number of people who say both that the United States “does too much” in helping to solve world problems and that it plays “a less important role” as a world leader are at record highs. But it’s not quite that simple. The “less important role” that the U.S. public envisions its government playing abroad still involves doing quite a lot of things. 56 percent think “U.S. policies [should] try to keep it so America is the only military superpower,” and on average Americans want to preserve current levels of defense spending. Large majorities said that “taking measures to protect the U.S. from terrorist attacks” (83 percent) and “preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction” (73 percent) should be “top priorities” among U.S. long-range goals.

This is a public, in short, that cares deeply about maintaining an overwhelmingly powerful military and taking decisive action against what it sees as core threats to American security—both central tenets of Jacksonian thinking. What the public doesn’t see as top priorities are things like “helping improve living standards in developing nations” (23 percent), “promoting democracy in other countries” (18 percent), and “promoting and defending human rights in other countries” (33 percent).

Does Raising The Minimum Wage Make Cents?

In his speech yesterday, Obama once again proposed increasing the minimum wage. Douglas Holtz-Eakin opposes the idea:

According to recent American Action Forum research, 80 percent of minimum wage workers are not actually in poverty, increasing the federal minimum to $10, as some have proposed, wouldn’t benefit 99 percent of the people in poverty. Myriad research indicates that raising the minimum wage, while not destroying jobs, impedes job creation. That means an even slower recovery to full employment. California’s new bump in the minimum wage to $10 will prevent the creation of almost 200,000 new jobs. If every state followed suit, more than 2.3 million jobs across the country would never see the light of day.

Ron Unz, who is trying to get a $12 minimum wage implemented in California, disagrees:

The impact on U.S. households would be enormous and bipartisan. Some 42 percent of American wage-workers would benefit from a $12 minimum wage and their average annual gain would be $5,000 per worker, $10,000 per couple, which is very serious money for a working-poor family. White Southerners are the base of today’s Republican Party, and 40 percent of them would gain, seeing their annual incomes rise by an average $4,500 per worker. If Rush Limbaugh — who earns over $70 million per year — denounced the proposal, they’d stop listening to him. Hispanics would gain the most, with 55 percent of their wage-workers getting a big raise and the benefits probably touching the vast majority of Latino families.

In the past, Unz has written that a higher minimum wage will reduce illegal immigration because “a much higher minimum wage serves to remove the lowest rungs in the employment ladder, thus preventing newly arrived immigrants from gaining their initial foothold in the economy.” Bruce Bartlett is made queasy by this rationale:

[I]t is not surprising that the Unz proposal has gotten strong support from those who strongly oppose immigration for racial reasons. The website VDARE.com (named for Virginia Dare, the first white child born in the New World) strongly supports it. A Feb. 20, 2013, commentary said a higher minimum wage would keep out “wetback labor.”

There are good arguments for raising the minimum wage. For example, an August study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago said an increase in the federal minimum wage would raise aggregate spending in the economy and, hence, the real gross domestic product. A higher minimum wage may also discourage some employment of illegal immigrants. But making an inadvertent side effect of the minimum wage its principal purpose may do more to divide potential allies than bring them together.

Steve Coll comments on the grassroots left’s campaigns for higher minimum wages:

The movement has momentum because most Americans believe that the federal minimum wage—seven dollars and twenty-five cents an hour, the same as it was in 2009—is too low. A family of four dependent on a single earner at that level—making fifteen thousand dollars a year—is living far below the federal poverty line. In January, President Obama called for raising the federal minimum to nine dollars an hour, and, more recently, he endorsed a target of ten dollars. Yet Congress has failed to act: a bill is finally heading for the Senate this month, but intractable Republican opposition in the House has made passage of any legislation in the short term highly unlikely. The gridlock has prompted local wage campaigns such as the one in SeaTac.

Arindrajit Dube discusses the broad appeal of such initiatives:

Support for increasing the minimum wage stretches across the political spectrum. As Larry M. Bartels, a political scientist at Vanderbilt, shows in his book “Unequal Democracy,” support in surveys for increasing the minimum wage averaged between 60 and 70 percent between 1965 and 1975. As the minimum wage eroded relative to other wages and the cost of living, and inequality soared, Mr. Bartels found that the level of support rose to about 80 percent. He also demonstrates that reminding the respondents about possible negative consequences like job losses or price increases does not substantially diminish their support.

Avent is unsure how companies would respond to a higher minimum wage:

The finding that an increase in the minimum wage boosts pay up the wage scale, and not just for those earning the minimum wage, is fascinating but also somewhat worrying. It suggests that the minimum wage does not primarily boost pay by reallocating the surplus generated by a hire. Instead, employees seem to respond by working harder while employers invest in training and other workplace productivity boosters. That’s a lovely thing to have happen, but also reason for caution. Technological progress seems to be boosting opportunities for automation all the time, and at some point firms will cross the threshold beyond which it makes sense to replace labour with capital rather than invest in more productive labour. Amazon’s fulfillment centres generate tens of thousands of jobs, many at or near minimum wage. Maybe a higher minimum wage will lead to better pay without much of an employment effect. Or maybe Amazon will accelerate the deployment of warehouse robots. Maybe a higher minimum wage will boost pay at fast-food restaurants. Or maybe it will lead the restaurants to get serious about automation.

I think ideally we would see a push instead for greater wage subsidies to low-income workers, perhaps combined with the careful minimum wage system used in Britain to ensure that firms don’t simply shift the burden of giving market pay rises onto the state.

Pethokoukis suggests an alternative to a minimum wage hike:

[A] 2010 study “Will a $9.50 Federal Minimum Wage Really Help the Working Poor?” by researchers Joseph Sabia and Richard Burkhauser found that a federal minimum wage increase from $7.25 to $9.50 per hour — higher than the $9 that President Obama has proposed — would raise incomes of only 11% of workers who live in poor households. Even Coy and Berfield acknowledge some of the policy’s imperfections, writing that “a higher wage floor would undoubtedly price some marginal workers out of the market.”

These studies aren’t some secret. So why do so many smart people keep advocating for a higher minimum wage? The best answer I can come up with is that they think it is more politically likely than the better economic answer: wage subsidies.

Drum doubts the GOP would go for it:

Wage subsidies would supposedly distort the labor market less than a higher minimum wage, but that’s because it would remove the onus of higher wages from employers and place it on the federal government. That means higher taxes to pay for the subsidy, and that’s just flatly a no-go for the modern Republican Party. This in turn means it could be implemented only as a tax credit, and that inherently places some restrictions on its reach and effectiveness. So Democrats would be in the position of backing either a good policy that will never get Republican support because it requires a tax increase, or else a mediocre policy that would still probably be a very heavy lift.

Always Tell Kids The Truth? Ctd

The thread takes an unexpected turn:

I laughed when I read what your reader wrote:

I have to object to the [previous] reader’s characterization of the “Christian tendency to turn religious holidays into occasions for inventing impossible narratives (a flying fat man and a giant bunny delivering toys and candy respectively)” I’m sorry, but that is a British/American tendency, not a Christian one. Spain, for one, did not turn either Easter or Christmas into any such thing, nor did any country in its vicinity.

Apparently he’s never heard of caga tió, the gift-shitting Christmas log:

The Tió de Nadal, popularly called Caga tió (“shitting log”), is a character in Catalan

mythology relating to a Christmas tradition widespread in Catalonia. The form of the Tió de Nadal found in many Catalan homes during the holiday season is a hollow log of about thirty centimetres length. Recently, the tió has come to stand up on two or four little stick legs with a broad smiling face painted on the higher of the two ends, enhanced by a little red sock hat (a miniature of the traditional Catalan barretina) and often a three-dimensional nose.

Beginning with the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (December 8), one gives the tió a little bit to “eat” every night and usually covers him with a little blanket so that he will not be cold at night.

On Christmas day or, depending on the particular household, on Christmas Eve, one puts the tió partly into the fireplace and orders it to defecate; the fire part of this tradition is no longer as widespread as it once was, since many modern homes do not have a fireplace. To make it defecate one beats the tió with sticks, while singing various songs of Tió de Nadal.

The tradition says that before beating the tió all the kids have to leave the room and go to another place of the house to pray asking for the tió to deliver a lot of presents. This makes the perfect excuse for the relatives to do the trick and put the presents under the blanket while the kids are praying.

The tió does not drop larger objects, as those are considered to be brought by the Three Wise Men. It does leave candies, nuts and torrons. Depending on the part of Catalonia, it may also give out dried figs. When nothing is left to “shit”, it drops a salt herring, a head of garlic, an onion or “urinates”. What comes out of the tió is a communal rather than individual gift, shared by everyone present.

Update from a reader:

You simply can’t inform your readers about the Caga Tio without also highlighting the peculiar custom of the Caganers. In Spain nativity displays (a belen) are very popular. My husband’s father has accumulated a nativity display that includes an entire village, farms, animals, etc. that takes days to set up. A feature called the “caganer” is a figure – a shepherd, villager etc. – who is obscurely placed in the belen and is often, well, taking a dump. Children (and adults) search the display to find the caganer. If you search shops and Christmas markets you can even find “action” caganers – with animated arms swiping a tiny tissue across their rear. And if that’s not strange enough, you can find innumerable examples of “celebrity” caganers – small figures of everyone from Queen Elizabeth to the Pope, President Obama to Madonna and every member of Real Madrid et al. – all taking a dump. Great gifts for back home if you happen to be in Barcelona over the holidays!

Not So Mad Max

As most outlets continue to ignore Goliath, Max Blumenthal’s scathing book on Greater Israel, Callie Maidhoff offers a critique from Max’s left:

[P]erhaps the largest problem with Goliath’s reception is that readers—and particularly liberal readers more accustomed to the “Shoot and Cry” body of literature — simply don’t recognize the Israel they know and love.

This is because coextensive with the hatred that Blumenthal so accurately depicts, is — for many people — an extremely warm, family-centered country, most of which is no longer willing to take to the streets for almost anything at all. This is the complicated, more difficult part of the story that doesn’t quite make it into Blumenthal’s telling: not that Israeli society is mostly friendly, reasonable, and not racist, but that this racism permeates Israeli law and society in ways that are often far more insidious than what goes into his book. And what Blumenthal calls ‘fascism’ is able to spread precisely because, for most Jews, Israel feels nothing like the nightmare that Blumenthal so dramatically describes.

Reading Goliath, for me, was a somewhat uncanny experience. Blumenthal’s tenure in Israel-Palestine lines up almost precisely with my own. The book picks up with Operation Cast Lead, the 2008-2009 Israeli offensive in Gaza during which I arrived for my first serious research trip in the country, and when I started reading the book, I was surrounded by boxes and suitcases, as I packed up to return to the States from a 10-month stint doing dissertation research on a Jewish Israeli settlement just east of the Green Line in the West Bank. As I read Goliath, I found that the author had lived on the same small street and in a very similar apartment as I did in Jaffa, just one year after I had. I found friends, contacts and, acquaintances making cameos or giving Blumenthal interviews. I recognized events where I myself had been present.

In short, I recognized the Greater Israel of Blumenthal’s account. But the key difference in our experience of this place, was that for Blumenthal, as a journalist, he mostly seems to have spoken his mind. He pushed people on the politics and the racism of their speech, and they pushed back. Blumenthal experienced the exclusionary politics of Israel that are invisible to most American Jews who visit that place.

Meanwhile, John Hudson reports that Max’s recent Q&A with seasoned foreign policy types at the New America Foundation went off without a hitch:

Last week, [John] Podhoretz attempted to shame the New America Foundation out of hosting Wednesday’s book chat. “NAF has crossed a line that no decent individual or group should even approach,” he wrote. “By doing so they are also sending a dangerous signal in the world of D.C. ideas that talk about doing away with Israel is no longer confined, as it should be, to the fever swamps of the far left or the far right.” …

If a think tank can’t have a book event, we’re not doing what we’re supposed to be doing,” Peter Bergen, the event’s moderator, told The Cable. “It was a public event and if they wanted to challenge [the book], it was open to anybody who wanted to come.” Bergen characterized the controversy surrounding the book as one of style versus substance. “The critiques of your book seem to be not as much about the facts,” he said during the event, “it’s more about the tone in the book.” But that doesn’t mean the think tank wasn’t prepared for significant or even violent blowback. On Wednesday, NAF sent out an all-staff e-mail notifying employees “we are hosting an event which requires additional security.” Elevators up to the event required a key swipe.

Surprisingly, Blumenthal didn’t take any flack during the event’s Q&A segment, which attracted a sympathetic crowd of Middle East enthusiasts who commended Blumenthal on his dedication to the topic.

“The Defining Challenge Of Our Time”

That’s how, in yesterday’s speech, Obama described America’s growing inequality:

The full speech can be viewed here. Ezra raves, calling it “perhaps the single best economic speech of his presidency”:

That’s in part because it exists for no other reason than to lay out Obama’s view of the economy. His other speeches on the subject have been about passing legislation, defining campaign themes, or positioning himself against Republicans. But Obama’s done running for office. He’s not getting anything through this Congress. And he’s not negotiating with John Boehner. This is just what he thinks.

I’m afraid I wasn’t as blown away, for some of the reasons John Cassidy notes:

In talking about the causes of rising inequality, he made the usual references to global competition and technological change, but without adding anything fresh. In laying out his policy prescriptions, he talked about promoting a “growth agenda,” which also sounded familiar: reforming the corporate tax code, eliminating loopholes, and using some of the money saved to invest in things like infrastructure and scientific research. As he has before, he came out in favor of strengthening the labor laws and raising the minimum wage. (By how much he didn’t say.) He spoke of improving educational standards, making pre-school programs more widely available, and pursuing a trade agenda that “works for the middle class.”

Most of these policies are individually worthwhile. But with the possible exception of a big hike in the minimum wage—a little one wouldn’t have much impact—they are mainly small-bore measures. Even if every one of them were enacted, which isn’t going to happen, it’s by no means clear that they would halt, much less reverse, the over-all trends that Obama highlighted.

Perhaps it’s best to see the speech as an attempt to generate a deeper understanding of the forces driving not a good inequality, but a potentially destructive one, restraining mobility and creating two separate nations out of one. Yglesias heard little in the speech about addressing unemployment:

The biggest applause line of the speech was about raising the minimum wage, which is great, but also doesn’t help you very much if your current wage is $0. Delivering a stemwinder about the need for Janet Yellen to raise the growth rate of nominal income in the United States might not have been very smart, but yadda-yaddaing past mass unemployment is odd.

The people suffering the most in this country aren’t the people’s whose wages are stagnating, it’s the people who don’t have any wages at all. And the biggest thing stopping the people whose wages are stagnating from demanding a raise is that there are all these unemployed people out there who’d love to have their crappy low-paying jobs.

Derek Thompson’s related points:

Social Security and Medicare, two of the most popular government programs today, work on the theory that there is a virtue to universalism. Obamacare is, well, slightly popular at the moment, but it works on the same principle. On jobs, however, it cannot be said the U.S. government has seriously considered universal (or, at least, full) employment anything near to a priority. We simply gave up early. It’s good and right to talk about income inequality for American workers. But when 20 million people are unemployed or marginally attached to the labor force, you’re going to have an awful income inequality crisis, no matter what your minimum and median wages look like.

Daniel Gross is pessimistic:

Obama—and other people who focus on Washington—are missing the forest for the thicket of policies. The real problem is that companies in the U.S. do not pay enough, and that they have conditioned themselves (and their investors, and board, and employees, and politicians) not to raise wages even as their profits and cash holdings rise to record levels. Consider that corporate profits have soared from $1.2 trillion in 2009 to about $2 trillion this year, and that between the end of 2006 and mid-2013, corporate America’s cash holdings rose from $850 billion to $1.48 trillion. And yet the response to this remarkable turnaround has been effectively to reduce wages. Median household income in 2012 was below where it was in 1999, and has risen in only five of the last 12 years (PDF).

This is not a problem that can be corroded by a higher minimum wage, or stronger unions, or universal pre-K. Rather, it would require a wholesale change of heart among America’s business class. They’d have to start taking pride in offering higher wages each year—rather than, say, offering higher dividends or stock buybacks each year. They’ve have to make it part of their strategic mission to aspire to pay above the median, and thus help drag wages up.

Amy Davidson talks to Robert Putnam, who is more upbeat:

From Putnam’s perspective, “any of those things is helpful”—including solutions outside of government—“but most important is a national understanding of the problem by ordinary people.” He compared the present moment, statistically and politically, to the Progressive Era, which also had a convergence of wealth, inequality, and a sense that the country had somehow become corrupt.

“And then, in about ten years, America fixed those problems,” Putnam said. “Child-labor laws, support for mothers, not to mention regulation of business, clean food. Government did it, in the face of a prevailing ideology of laissez-faire—social Darwinism, as it was called.” What made the difference was a moral shift: “People said, ‘This is not the way it should be. This is not America.’ ” He thought it was happening again. So where in that ten-year pattern might we be? Putnam wasn’t sure, but hoped it could be speeded up.

Yglesias Award Nominee

“Some advocates of war [with Iran] seem gripped by Thirties Envy, a longing for the clarity of the 1930s, when appeasement failed to slake the dictators’ thirst for territorial expansion. But the incantation “Appeasement!” is not an argument. And the word “appeasement” does not usefully describe a sober decision that war is an imprudent and even ultimately ineffective response to the failure of diplomatic and economic pressures to alter a regime’s choices about policies within its borders,” – George F Will.