In an excerpt from their new book, Larry Downes and Paul Nunes explain how disruptions in the tech market work:

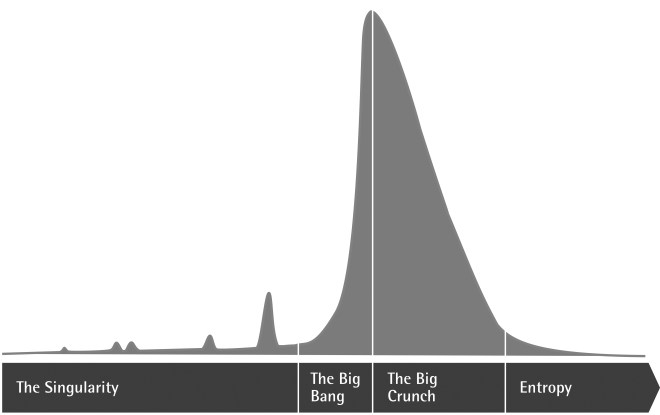

[T]oday, new products and services enter the market better and cheaper right from the start. So producers can’t rely on a class of early adopters and high margins to build up a war chest to spend on marketing to larger and later markets. For better and for worse, thanks to near-perfect market information, consumers are too savvy for that. Everyone knows right away when some new offering gets it right — or, conversely, gets it wrong. The bell curve, once useful as a model of product adoption, has lost its value as a planning tool. This kind of disruption has its own unique life cycle, and with it its own best practices for marketing and sales, product enhancement, and eventual product replacement. Markets take off suddenly, or they don’t take off at all. Since adoption is increasingly all-at-once or never, saturation is reached much sooner in the life of a successful new product. So even those who launch these “Big Bang Disruptors” — new products and services that enter the market better and cheaper than established products seemingly overnight — need to prepare to scale down just as quickly as they scaled up, ready with their next disruptor (or to exit the market and take their assets to another industry).

They give the example of Kinect, an add-on to Microsoft’s Xbox 360:

Kinect was an enormous hit, selling eight million units in just the first sixty days. According to Guinness World Records, that made Kinect the fastest-selling consumer electronic device in history. A little over a year after launch, twenty-four million Kinects had been sold, pushing sales of Xbox 360 consoles and games along with it. In 2010, Microsoft took the top spot in the fiercely competitive console market for the first time since Xbox 360’s launch in 2001. For Big Bang Disruptors, however, catastrophic success invariably leads to rapid market saturation — and with it decline and sunset. Within six months, the pace of Kinect sales dropped precipitously. Though stragglers continued to buy the product in peaks and valleys over the next year, the product had largely fulfilled its mission in its first ten months. For Microsoft — and other game developers — it was time for another innovation.