Derek Thompson marks the 50th anniversary of Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, partly blaming the problem’s stickiness on the rise of the single-parent household:

The poverty rate among married couples is quite low: 6 percent. The poverty rate among single-dads/moms is quite high: 25/31 percent. Since the share of single-parent households doubled since 1950, we should expect it to stress the poverty rate, especially since low-income people closer to the poverty line are less likely to marry, in the first place. Things get really interesting when you zoom into the marriage picture. Among what you might consider “modern families” (e.g. the 61 million people married and living together, both working), there is practically no poverty. None. Among marriages where one person works and the other doesn’t (another 36 million Americans) the poverty rate is just under 10 percent.

But take away one parent, and the picture changes rather dramatically. There are 62 million single-parent families in America. Forty-one percent of them (26 million households) don’t have any full-time workers. This is something beyond a wage crisis. It’s a jobs crisis, a participation crisis—and it’s a major driver of our elevated poverty rate.

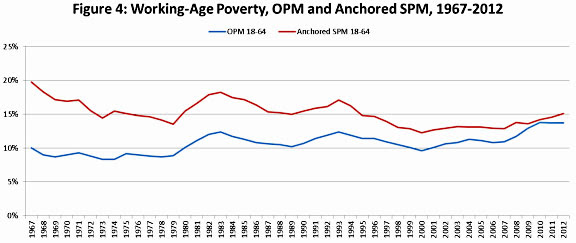

Drum touches on the anniversary as well, passing along the above chart and noting that he sees the war as more of a stalemate:

The Great Society programs of the 60s got the working-age poverty rate down from 20 percent to 15 percent, but then we gave up. Since the mid-70s, the poverty rate has stayed stubbornly stuck at about 15 percent[.] This is a chart to really keep in mind as you read the inevitable retrospectives. The overall poverty rate has gone down substantially in the past half century, but that’s largely because of the huge effect of Social Security on elderly poverty. But as much as this is a great achievement, it’s not what most people think of when you talk about “poverty.” Rather, they’re mostly thinking of working-age people who are either unemployed or earning tiny wages. And among those people, we simply haven’t done much for the past 40 years.

Jared Bernstein points out that poor families are up against a worse economic climate than they faced a few decades ago:

The data clearly show that anti-poverty policies have been effective, but they’ve had to work harder in the face of increasing economic challenges facing low-income families. We could try to push the safety net further, but the politics aren’t there, to say the least. Moreover, unless we do more to deal with the underlying structural problems in the economy that are increasing poverty — especially the lack of decently paying jobs, which I link closely to the absence of full employment — we’ll have to increasingly ratchet up government support year after year.

The American safety net is actively helping millions of economically disadvantaged families, and we should protect and improve it. But the best way to help it — and more importantly, the poor themselves — is to strengthen the underlying economy in ways that will take some of the pressure off of what has, over the last 50 years, become an effective set of anti-poverty social policies.

Flavelle argues that the Republicans have a point in criticizing the anti-poverty project:

[T]he OECD data suggest that for every dollar of social spending, the U.S. gets less poverty reduction than other developed countries. There are plenty of possible explanations for that, including poorly run programs; spending that is disproportionately focused on certain groups (such as the elderly); and noneconomic barriers facing some minorities. Another explanation could be the share of social spending that comes in the form of cash, rather than services. U.S. social spending is evenly split between cash benefits and services; in France, cash makes up almost two-thirds of the balance, according to the OECD.

Whatever the reasons, the combination of relatively high social spending and relatively low poverty reduction gives credence to a main plank of Republicans’ argument: When it comes to the war on poverty, the current approach isn’t working that well, in terms of getting the most value for what the U.S. is already spending. What should be done differently is another question.

But Zeke J Miller, Maya Rhodan, and Alex Rogers don’t see the parties coming together on this issue anytime soon:

Both sides largely reject the others’ proposals as misguided. “The goal ought to be, is to get people out of entry-level jobs, into better jobs, better-paying jobs. That’s better education. That’s a growing economy,” Ryan said in response to President Obama’s State of the Union last year. “I don’t think raising the minimum wage, and history is very clear about this, doesn’t actually accomplish those goals.” Democrats object that Republicans are trying to gut welfare programs and public education with their so-called reforms. At the root of the dueling rhetoric around the The War on Poverty is a political question: Does the government enable, or is it an enabler? “There is a lot more clarity on the current trends in inequality than there is on what to do about it, much less any agreement,” said Isabel Sawhill, Senior Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution. “Amongst experts there is much more clarity. We need a bipartisan agreement about what to do about inequality because if we don’t nothing will happen.”