A New America Foundation study calls into question the government’s claims about the NSA’s metadata dragnet:

Surveillance of American phone metadata has had no discernible impact on preventing acts of terrorism and only the most marginal of impacts on preventing terrorist-related activity, such as fundraising for a terrorist group. Furthermore, our examination of the role of the database of U.S. citizens’ telephone metadata in the single plot the government uses to justify the importance of the program – that of Basaaly Moalin, a San Diego cabdriver who in 2007 and 2008 provided $8,500 to al-Shabaab, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia – calls into question the necessity of the Section 215 bulk collection program.

According to the government, the database of American phone metadata allows intelligence authorities to quickly circumvent the traditional burden of proof associated with criminal warrants, thus allowing them to “connect the dots” faster and prevent future 9/11-scale attacks. Yet in the Moalin case, after using the NSA’s phone database to link a number in Somalia to Moalin, the FBI waited two months to begin an investigation and wiretap his phone. Although it’s unclear why there was a delay between the NSA tip and the FBI wiretapping, court documents show there was a two-month period in which the FBI was not monitoring Moalin’s calls, despite official statements that the bureau had Moalin’s phone number and had identified him. This undercuts the government’s theory that the database of Americans’ telephone metadata is necessary to expedite the investigative process, since it clearly didn’t expedite the process in the single case the government uses to extol its virtues.

Meghan Neal is unsurprised:

This is hardly the first time experts have searched for a link between bulk metadata collection and foiled terrorist plots and come up empty-handed. So far, the only real value in collecting and monitoring billions of US phone records has been to provide extra support in investigations already underway by the FBI or another agency, or to verify that a rumored threat isn’t real (the “peace of mind” metric), the report found. But that hasn’t stopped NSA officials and the Obama administration from drumming up a connection between terrorist attacks and surveillance to defend the agency’s snooping.

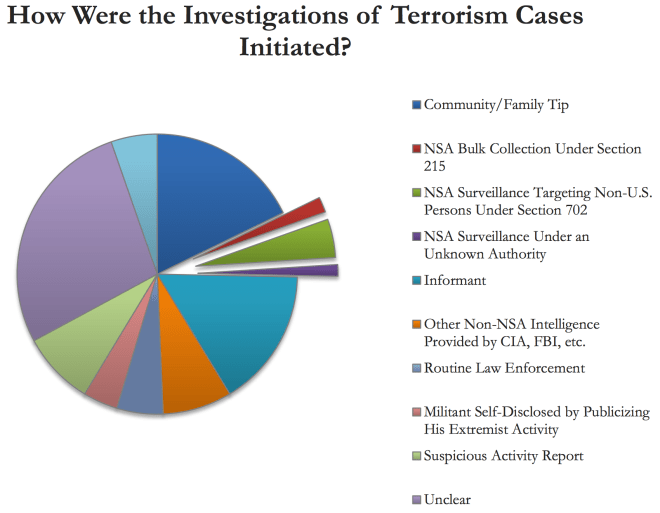

Morrissey examines the pie chart seen above and asks if the program is worth it:

What has been the most effective method? Of those explicitly stated, it’s “if you see something, say something.” Community and family tips accounted for 17.8% of the origins of investigations, followed closely by 16% started by other informants. However, 27.6% are categorized as “unclear” — the largest single category, which makes the analysis much less reliable, and might raise questions about how the NSA got those FISA warrants. Still, there were four cases unearthed through Section 215 (and possibly more in the “unclear” category). Is that enough to justify the program as a necessary evil to prevent worse evil from prevailing?

Zack Beauchamp thinks not:

NSA metadata collection isn’t totally useless; it’s just not very useful. When you start to look at the specific cases that metadata surveillance played a key role in, the picture gets grimmer for the NSA. The New America researchers found that metadata searches never led to an arrest that actually prevented a terrorist attack. Take, for instance, the arrest of Basaaly Moalin — the only case, according to NSA Director Keith Alexander’s sworn testimony, metadata surveillance may have sparked an investigation that stopped “terrorist activity.” All the government found on Moalin was $8,500 donated to Somali terrorist group al-Shabaab; “the case involved no attack plot anywhere in the world,” according to New America’s review. In almost all of the cases profiled by New America, metadata surveillance played a supporting role, unnecessarily displaced traditional investigative methods, or failed to uncover a serious plot.

Digby reminds us that for all it doesn’t do, this data program costs an awful lot of money:

And keep in mind this whole thing is happening in the context of an ongoing, long term austerity push that has us cutting off the long term unemployed and ending food stamp benefits. That Utah data farm alone cost 1.2 billion and is reportedly going to cost at least a couple billion more before it’s online. There was a moment in the early days of the NSA story in which we discussed the incredible boondoggle all this really was but it passed as the revelations unfolded. It’s good that the congress has decided to shine a light on that again, however briefly, in this budget process. After all, we have real people suffering in a stuck economy without enough jobs. We have a growing poverty rate. Our bridges and schools are crumbling. And yet the money for the military, police and all these attendant “intelligence” agencies has been kept secret until now. It’s only right that the people should at least know what the numbers really are.