Greg Grandin researches “the way the advancement of medical knowledge was paid for with the lives of slaves”:

The death rate on the trans-Atlantic voyage to the New World was staggeringly high. Slave ships, however, were more than floating tombs. They were floating laboratories, offering researchers a chance to examine the course of diseases in fairly controlled, quarantined environments. Doctors and medical researchers could take advantage of high mortality rates to identify a bewildering number of symptoms, classify them into diseases, and hypothesize about their causes.

Corps of doctors tended to slave ports up and down the Atlantic seaboard. Some of them were committed to relieving suffering; others were simply looking for ways to make the slave system more profitable. In either case, they identified types of fevers, learned how to decrease mortality and increase fertility, experimented with how much water was needed for optimum numbers of slaves to survive on a diet of salted fish and beef jerky, and identified the best ratio of caloric intake to labor hours. Priceless epidemiological information on a range of diseases — malaria, smallpox, yellow fever, dysentery, typhoid, cholera, and so on — was gleaned from the bodies of the dying and the dead.

Update from a reader:

It’s important to note that this experimentation on slaves was an ongoing practice. For example, there is the case of J. Marion Sims, considered the “Father of Modern Gynecology.”

Sims created some of the first basic tools for gynecological examination. But these breakthroughs came through the experimentation of untold, and largely unnamed, slave women (and later in New York City on destitute Irish immigrant women). I learned about Sims a few years ago on a visit to the State Capitol grounds in Columbia, South Carolina which features a beautiful memorial to Sims that presents him as a great hero and pioneer. There have been attempts to “right the record” and include a more complete story of his record along with the heroic inscriptions. These would include the sheer numbers of forced patients and the staggering numbers of surgeries (30 known on one patient). These were all done without anesthetic, which was known and used at that time. In any case it didn’t matter. The pain of the patient wasn’t a consideration. Gynecological problems that impeded their value as bearers of more slaves was what Sims was attempting to solve in these surgeries.

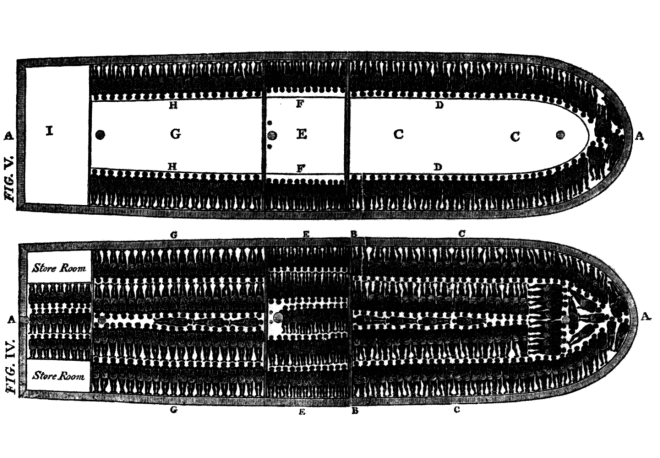

(Illustration: Diagram of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade. Via Wikimedia Commons)