by Patrick Appel

According to a recent report, Google Flu Trends has major problems:

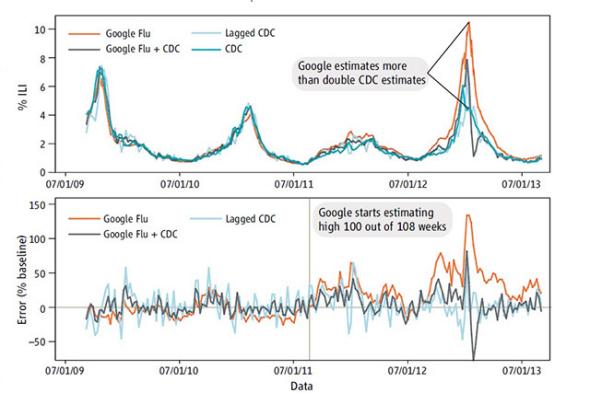

Flu Trends has gotten it badly wrong in at least two cases. The reason for these errors is remarkably simple: the flu was in the news, and people were therefore more interested and/or concerned about its symptoms. Use of the key search terms rose, and, at some points, Google Flu Trends predicted double the number of infected people than were later revealed to exist by the Centers for Disease Control data. (One of these cases was the global pandemic of 2009; the second an early and virulent start to the season in 2013.)

On its own, this isn’t especially damning. But the authors note that flu trends have consistently overestimated actual cases, estimating high in 93 percent of the weeks in one two-year period. You can do just as well by taking the lagging CDC data and putting it into a model that contains information about past flu dynamics. And, unlike the Flu Trends algorithm, they point out that this sort of model can be improved.

David Auerbach takes Google to task:

One of the main problems is that Google’s data is private—very private. Google does not release its raw data or the details of its analyses or even the set of keywords it uses for a particular result. This makes the studies impossible to replicate or check . . . Even if Google’s methodology is perfect—and there’s reason to believe it’s not—there needs to be validation. Here Google’s corporate and research agendas come into conflict: If it wants credit for scientific research, it needs to show its work, even at the cost of compromising competitive advantage.

But the project can be salvaged:

As a test, the researchers created a model that combined Google Flu Trends data (which is essentially real-time, but potentially inaccurate) with two-week old CDC data (which is dated, because it takes time to collect, but could still be somewhat indicative of current flu rates). Their hybrid matched the actual and current flu data much more closely than Google Flu Trends alone, and presented a way of getting this information much faster than waiting two weeks for the conventional data.

“Our analysis of Google Flu demonstrates that the best results come from combining information and techniques from both sources,” Ryan Kennedy, a University of Houston political science professor and co-author, said in a press statement. “Instead of talking about a ‘big data revolution,’ we should be discussing an ‘all data revolution.'”