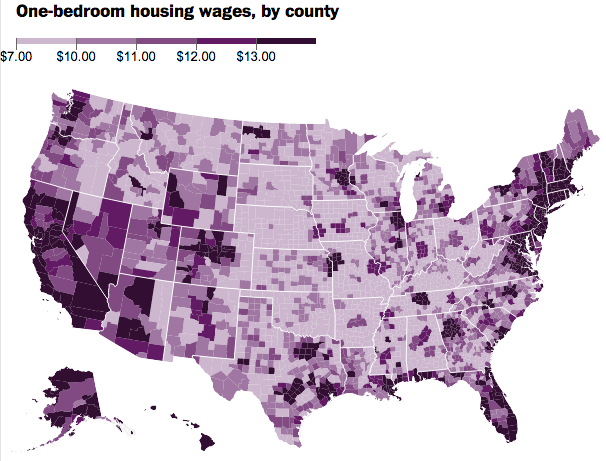

Emily Badger and Christopher Ingraham map how much it costs to rent a one-bedroom residence in every US county (interactive version here):

No single county in America has a one-bedroom housing wage below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 (several counties in Arkansas come in at $7.98).

Coastal and urban counties are among the most expensive. The entire Boston-New York-Washington corridor includes little respite from high housing wages. Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties in California rank as the least affordable in the country (scroll over each county in the interactive version for rankings; click to zoom). In each of those counties, a one-bedroom hourly housing wage is $29.83, or the equivalent of 3.7 full-time jobs at the actual minimum wage (or an annual salary of about $62,000). Move inland in California, and housing grows less expensive.

But renting is often a better deal than buying. Catherine Rampell is shocked that we still consider home buying a great investment:

“People forget that housing deteriorates over time. It goes out of style. There are new innovations that people want, different layouts of rooms,” [Robert Shiller] told me. “And technological progress keeps bringing the cost of construction down.” Meaning your worn, old-fashioned home is competing with new, relatively inexpensive ones.

Over the past century, housing prices have grown at a compound annual rate of just 0.3 percent once one adjusts for inflation, according to my calculations using Shiller’s historical housing data. Over the same period, the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index has had comparable annual returns of about 6.5 percent.

Yet Americans still think it’s financially savvy to dump all their savings into a single, large, highly illiquid asset.

She follows up with concrete numbers:

Let’s imagine you bought the country’s median-priced house in 1982 for $69,000. I, on the other hand, rented a home for $400 (that’s actually much higher than what the Labor Department estimates the monthly rental value of an owned home was around that time, but I’m trying to be conservative about how expensive it is to rent vs. buy). I also invested $69,000 in the S&P 500.

To keep the example simple, let’s also assume you paid cash for the house –interest rates were about 16% in 1982, after all — and I am paying my rent out of my stock market account each year. Thirty years later, given national housing price changes, you’d be left with a house worth about $213,000, which is a little bit less than today’s national median new home sales price. (Your house is 30 years old after all, and today’s homes are bigger.) On the other hand, looking at how much rents have risen over the same period nationwide and how much the S&P 500 has grown, I’d have about $719,000 in my Vanguard account. And we both had somewhere to live.

But Rampell acknowledges that houses aren’t simply investments:

Fannie Mae, in its National Housing Survey, asks Americans about “the best reason to buy a house,” giving them two options: “financial benefits” (like investment, wealth building, and tax benefits), or ”the broader security and lifestyle benefits of homeownership” (like providing a good and secure place for your family, control to make renovations, etc.) In the March survey, 43 percent of respondents choose the ”financial benefits,” while 55 percent chose “the broader security and lifestyle benefits.” So yes, the psychic benefits of ownership appear to be a bigger driver for buying a house than the financial ones.

But here’s the part that’s irksome: The same survey also asked people to rate different kinds of investments as a “safe investment with a lot of potential,” “safe investment with very little potential,” “risky investment with very little potential,” or “risky investment with a lot of potential.” Buying a home is almost always the option with the highest share of respondents calling it a “safe investment with a lot of potential.”