A new study finds that people opposed to marriage equality shift dramatically when they are engaged in argument – especially when a gay person does the engagement. A better approach, I’d say, than writing them all off as bigots.

Month: April 2014

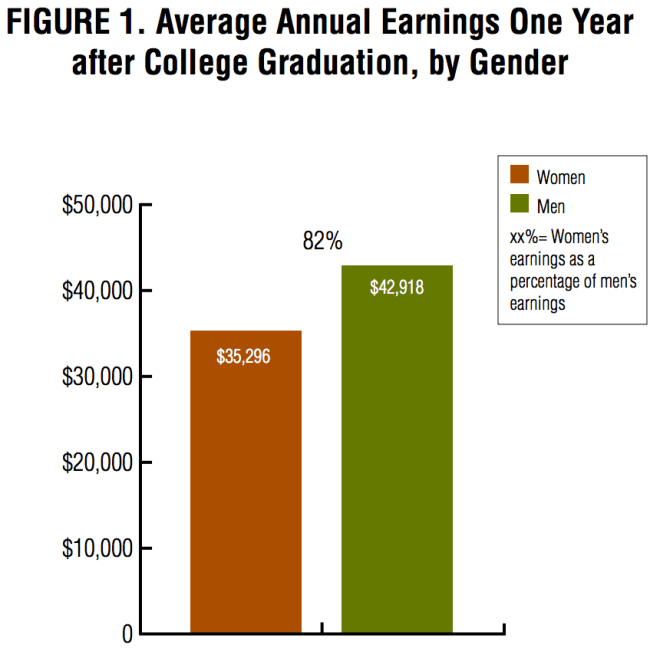

Sizing Up The Pay Gap

To mark “Equal Pay Day,” Obama is signing two executive orders setting new pay equity rules for federal contractors. Waldman explains what these EOs will do:

The first order will bar contractors from retaliating against employees who discuss their compensation with each other. This was a factor in [Lilly] Ledbetter’s case — like many victims of pay discrimination, it took her years to discover she was being paid less than her male colleagues, because no one talked about it. And there are many employers who actually bar their employees from discussing their pay. The second order requires contractors to provide data to the government on employee compensation, broken down by sex and race. With those data in hand, the government will be able to see whether employees are being treated equally.

Jay Newton-Small examines the Democrats’ full-court press on pay equity. But Z. Byron Wolf notes that the much-cited “77 cents on the dollar” figure is misleading:

[That figure] is calculated by adding all the wages of women and dividing the total by all the wages of men. But that doesn’t take into account a lot of factors, like women taking time off work to have children or choosing different career paths. Professional fact checkers at Factcheck.org (“exaggeration”), Politifact (“Mostly False”) and The Washington Post (“one Pinocchio”) have all found problems with the claim. The American Association of University Women released a report that concluded the pay gap was closer to 7% than 23%.

Andrew Biggs and Mark Perry argue that the wage gap is even smaller:

While the BLS reports that full-time female workers earned 81% of full-time males, that is very different than saying that women earned 81% of what men earned for doing the same jobs, while working the same hours, with the same level of risk, with the same educational background and the same years of continuous, uninterrupted work experience, and assuming no gender differences in family roles like child care. In a more comprehensive study that controlled for most of these relevant variables simultaneously—such as that from economists June and Dave O’Neill for the American Enterprise Institute in 2012—nearly all of the 23% raw gender pay gap cited by Mr. Obama can be attributed to factors other than discrimination. The O’Neills conclude that, “labor market discrimination is unlikely to account for more than 5% but may not be present at all.”

Bryce Covert pushes back against these claims:

It’s fair to say that not all of the gap is due to discrimination. Certainly women are clustered in low-wage work — they are about two-thirds of the country’s minimum wage workers — and often have to interrupt their careers to care for family members, all of which impacts their earnings.

But even when various factors like these are taken into account, the entire gap doesn’t disappear. When the Government Accountability Office last looked at the gap, it couldn’t explain 20 percent of the disparity in pay between men and women, something that could be at least in part caused by discrimination. A more recent study by economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn found that while experience, occupation, and industry explain much of the gap, there is still more than 40 percent of it that remains unexplained, the part that could be chalked up to discrimination. We can also look to the real world to see instances where it’s clear that outright discrimination is still at play, such as the details of a recent class action lawsuit against the country’s largest jewelry store, where female employees across the country and with substantial experience say they were still paid less than less qualified men.

(Chart from The American Association of University Women (pdf))

“Waterboard Him Some More”

If you’re still in any way curious why several CIA figures – and Liz Cheney – are losing their shit right now – and getting space to say nothing in the Washington Post – this piece by Katherine Hawkins might help. It confirms one particular instance that Senator McCain told the National Journal on Monday:

Officials waterboarding a terror suspect reported to CIA headquarters that they had “gotten everything we can out of the guy.” The message came back, ‘Waterboard him some more.’ That is unconscionable,” McCain said.

I wonder if Jose Rodriguez had anything to do with that.

Nigeria Is Number One

John O’Sullivan explains how, in just one weekend, Nigeria catapulted over South Africa to become the continent’s top economy:

On Saturday, April 5, South Africa was Africa’s largest economy. The IMF put its GDP at $354 billion last year, well ahead of its closest rival for the crown, Nigeria. By Sunday afternoon that had changed. Nigeria’s statistician-general announced that his country’s GDP for 2013 had been revised from 42.4 trillion naira to 80.2 trillion naira ($509 billion). The estimated income of the average Nigerian went from less than $1,500 a year to $2,688 in a trice. How can an economy grow by almost 90 percent overnight?

Nigeria has a deserved reputation for corruption, so a sceptic might think the doubling of its economy a result of fiddling the numbers. In fact it is the old numbers that are dodgy. An economy’s real growth rate is typically measured by reference to prices in a base year. In Nigeria the reference year for the old estimate of GDP was 1990. The IMF recommends that base years be updated at least every five years. Nigeria left it far too long; as a result, its old GDP figures were hopelessly inaccurate.

Uri Friedman notes that “in computing its GDP all these years, Nigeria, incredibly, wasn’t factoring in booming sectors like film and telecommunications”:

The Nigerian movie industry, Nollywood, generates nearly $600 million a year and employs more than a million people, making it the country’s second-largest employer after agriculture. As for the telecom industry, consider that there are now some 120 million mobile-phone subscribers in Nigeria, out of a population of 170 million. Nigeria and South Africa are the largest mobile markets in sub-Saharan Africa, and cell-phone use has been exploding in the country. Incorporating the film and telecom industries into Nigeria’s GDP made a huge difference in the services sector, rendering the country’s economy not just bigger but more diversified.

And that may be good news for developing countries around the world:

Cases like Nigeria’s indicate that “Africa as a whole probably is not as poor as we’ve long thought,” the economist Diane Coyle writes in her great (and well-timed) new book, GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History. “In many African, Asian, and Latin American economies, the GDP calculations take no account of phenomena such as globalization, or the mobile phone revolution in the developing world. … [O]ne estimate suggests that for twenty years sub-Saharan African economies have been growing three times faster than suggested by the ‘official’ data.”

A bright continent indeed. John Campbell wonders how this development will effect Nigeria’s international standing:

The claim of being Africa’s largest economy could bolster Nigeria’s chances of joining the G-20; at present, South Africa is the only African country in the club. But, if Nigeria joins, does South Africa leave? It might also strengthen Nigeria’s claim to a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, if and when Security Council enlargement becomes anything more than a hypothetical question. And what about the BRICS (the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa)? South Africa’s membership was predicated on being Africa’s “largest economy.” Will Nigeria displace South Africa, or join South Africa?

(Photo: A Nigerian fan celebrates her team’s victory over Ethiopia after a 2014 World Cup qualifying match in Addis Ababa on on October 13, 2013. By Simon Maina/AFP/Getty Images)

Is “Opting Out” Copping Out?

Anya Kamenetz observes the growing movement of parents keeping their kids home on standardized test days:

The spring of 2014 has seen a wave of grassroots activism against both standardized tests and the Common Core that Bob Schaeffer, a longtime activist with the group Fairtest, calls “unprecedented.” The numbers are small, but they’re found around the country. … It is unusual for parent activists in heavily democratic Greenpoint, Brooklyn, to be on the same page with those in more conservative Syracuse, hundreds of miles away in Western New York. But the same pattern is repeating around the country. The convergence of resistance to the Common Core, a cause championed by libertarian and other right-wing groups, with resistance to state standardized tests, often backed by progressive teachers’ unions and civil rights groups, has led to what Schaeffer calls a “strange-bedfellows alliance.”

Michelle Chen is sympathetic to the movement in New York, where students are taking standardized tests this week. But Michelle Rhee slams the trend:

Opt out of measuring how well our schools are serving students? What’s next: Shut down the county health department because we don’t care whether restaurants are clean? Defund the water-quality office because we don’t want to know if what’s streaming out of our kitchen faucets is safe to drink? …

Tests serve many purposes: They chart progress. They identify strengths and weaknesses. They help professionals reach competency in their careers. All these measures are critical to improving public schools. After all, the children sitting in classrooms today are going to grow up and compete for jobs with people in India and China and Europe, not just with people in the state next door. It’s our civic duty to make sure these kids are ready.

Valerie Strauss pushes back:

The scores of the most important end-of-year standardized tests don’t actually come back to the districts until the summer, making it impossible for teachers to use the results to help tailor instruction to a particular child – if in fact the tests actually gave important information to the teacher. Which by and large they don’t, because so many of the tests are badly drawn. Even Rhee admits this in her op-ed:

We don’t need to opt out of standardized tests; we need better and more rigorous standardized tests in public schools. Well-built exams can tell us whether the curriculum is adequate. They can help teachers hone their skills. They can let parents know whether their child’s school is performing on par with the one down the street, or on par with schools in the next town or the neighboring state.

Well, if we need better and more rigorous tests, why has she condoned the use of badly constructed exams all these years?

Mental Health Break

How do you get a whole city to walk backwards?

What you’re really seeing:

The opposite of which is actually true: the man, Ludovic Zuili, is the one walking backward but the video is being played in reverse. What you’re watching is just a short preview of a 9-hour movie that was aired in its entirety in France called Tokyo Reverse, part of a bizarre TV programming trend called Slow TV that has been regarded as a “small revolution.” According to the BBC, similar video projects aired in Norway include a 6-day video of a ferry journey through the fjords which attracted viewership of more than half the country.

Is straight reality, in real-time, the new reality TV? We’ll find out soon here in the U.S.

Deluged By Data

In a review of Fortune Tellers: The Story of America’s First Economic Forecasters by Walter A. Friedman, James Surowiecki considers a problem facing modern forecasters – “there may actually be too much information out there”:

Now, Herbert Hoover would have said this deluge of data was a good thing. He believed that if businesspeople had access to more information about how the economy was doing, they would act in what economists call a countercyclical fashion. In other words, if they understood that the economy was on the verge of overheating, they’d be more cautious, and vice versa. But it seems just as likely that there are times when the flood of information leads businesspeople and investors to jump on the bandwagon instead—acting recklessly in boom times and too cautiously when things are slow, which ends up amplifying the trend, rather than countering it. Markets and economies work best when people are able to think for themselves. But when everyone is shouting at the same time, it can be hard to do that.

The real issue here is one that the economist Oskar Morgenstern identified back in the late 1920s—namely, that economic predictions actually end up shaping the very outcomes they’re trying to predict. And the more predictions you have, the more complex that Möbius strip becomes. In that sense, for all the challenges they faced, men like [business theoriest Roger] Babson and [economist Irving] Fisher had it easy, since forecasts were few and far between. The real irony of our forecasting boom is that as fortune-tellers proliferate, fortunes become harder to read.

Ukraine? Where’s That?

Most Americans can’t find it on a map, according to this survey and an accompanying map:

If you think you can identify Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 on a map but not Ukraine, it’s time to watch less CNN.

— LOLGOP (@LOLGOP) April 7, 2014

Details on that survey:

About one in six (16 percent) Americans correctly located Ukraine, clicking somewhere within its borders. … However, the further our respondents thought that Ukraine was from its actual location, the more they wanted the U.S. to intervene militarily. Even controlling for a series of demographic characteristics and participants’ general foreign policy attitudes, we found that the less accurate our participants were, the more they wanted the U.S. to use force, the greater the threat they saw Russia as posing to U.S. interests, and the more they thought that using force would advance U.S. national security interests; all of these effects are statistically significant at a 95 percent confidence level.

These findings don’t surprise Larison:

It makes sense that ignorance about a country’s location and its importance to U.S. security would be associated with a preference for more aggressive policies. Those that know the least about the country and U.S. interests presumably would be more likely to accept arguments that exaggerate the threat to the U.S., especially if they are relying on news sources that sensationalize the events and hype the threat in order to attract an audience. Because these respondents have a poorer understanding of the most basic facts, the more likely they are to fall for alarmist demands for “action” and the less likely they are to have considered the considerable dangers and costs that a hard-line response would almost certainly entail.

But John Patty complains that the survey is being used to ridicule people who don’t deserve it:

There are a lot of clicks in Greenland, Canada, and Alaska. … clicking farther away from Ukraine means that you are, with some positive (and in this case, significant) probability clicking closer to the United States. So, suppose that the study said “those who think the Ukraine is located close to the US are more likely to support military intervention to stem Russian expansion?” Would that be surprising? Would that make you think voters are irrational?

The New War Lit

George Packer seeks a common thread in the memoirs, poetry, and fiction by soldiers who served in the most recent American conflicts:

Iraq was … different from other American wars. (So far, almost all the new war literature comes from Iraq, perhaps because there weren’t many troops in Afghanistan until 2009, and the minimum lag time between deployment and publication seems to be around five years.) Without a draft, without the slightest sacrifice asked of a disengaged public, Iraq put more mental distance between soldiers and civilians than any war of its duration that I can think of. The war in Iraq, like the one in Vietnam, wasn’t popular; but the troops, at least nominally, were—wildly so. (Just watch the crowd at a sports event if someone in uniform is asked to stand and be acknowledged.)

Both sides of the relationship, if they were being honest, felt its essential falseness.

A tiny number of volunteers went off to fight, often two or three times, in a war and a country that seemed incomprehensible. They returned to heroes’ welcomes and a flickering curiosity. Because hardly anyone back home really wanted to know, the combatant’s status turned into a mark of otherness, a blessing and a curse. The title of David Finkel’s recent book about the struggles of soldiers returned from Iraq, “Thank You for Your Service,” captures all the bad faith of a civilian population that views itself as undeserving, and the equivocal position of celebrated warriors who don’t much feel like saying, “You’re welcome.”

So it’s not surprising that the new war literature is intensely interested in the return home. The essential scene of First World War writing is the mass slaughter of the trenches. In the archetypal Vietnam story, a grunt who can never find the enemy walks into physical and moral peril. In much of the writing about Iraq, the moment of truth is a reunion scene at an airport or a military base—families holding signs, troops looking for their loved ones, an unease sinking deep into everyone.

Tumblr Of The Day

At the beginning of spring in Central Texas, it’s tradition to take photos of loved ones among the newly blossomed bluebonnets. On the Internet, it’s tradition to crap on traditions:

Many more here. Update from a reader:

Really, Andrew? Rather childish, don’t you think?

No disagreement here.