“The introduction of same-sex civil marriage says something about the sort of country we are. It says we are a country that will continue to honour its proud traditions of respect, tolerance and equal worth. It also sends a powerful message to young people growing up who are uncertain about their sexuality. It clearly says ‘you are equal’ whether straight or gay. That is so important in trying to create an environment where people are no longer bullied because of their sexuality – and where they can realise their potential, whether as a great mathematician like Alan Turing, a star of stage and screen like Sir Ian McKellen or a wonderful journalist and presenter like Clare Balding,” – Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, celebrating the dawn of marriage equality in Britain.

Month: April 2014

The Painted Selfie

In a review of The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History, Peter Conrad argues that early self-portraiture was “averse to vanity”:

Unusually, Hall’s history begins in the middle ages, because for him self-portraiture emerges as a reflex of Christian conscience, a homage to Christ’s imprinting of his agonized face on the Turin shroud. But the imitation of Christ takes courage, and it usually ends in the artist’s self-castigation. Previewing the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo actually flays himself: St. Bartholomew grips the painter’s empty epidermis, which has been painfully peeled off with a butcher’s knife.

Such stark portrayals are averse to vanity. Behind the sedate married couple in The Arnolfini Portrait, Van Eyck includes his miniaturized self reflected in a mirror – a kind of signature, but also, according to Hall, a recollection of Seneca’s claim that mirrors were invented as an aid to self-knowledge, not to encourage primping and preening. Even Dürer’s florid tresses, waxed into permanent waves when he paints himself as Christ, are more than a fancy coiffure: his hair, growing directly out of the brain, testifies to the efflorescence of his spiritual thoughts.

Mark Hudson sees something recognizably modern in such work:

The notion of the artist constructing themselves as a character in their own work may sound like an arch postmodern conceit, but from the late 15th century artists were manipulating their self-images, making themselves appear older or younger to suit their purposes, taking on fictional and biblical roles to heighten their brand profiles. Andrea Mantegna, the “richest and most famous artist of the time”, portrayed himself as a grim-faced Roman in his memorial bust, “his tumescent bulldog features” conveying a “visceral machismo”. Comparing himself in the accompanying inscription to Apelles, court artist of Alexander the Great, he brought the reflected glory of the Greek conqueror on himself and his patrons, the Gonzagas.

Meanwhile, Frances Spalding notes that self-portraits have attracted relatively little attention from art historians:

It’s hard to understand why self-portraits, as a genre, have until now been so little discussed. They include some of the greatest works of all time. Among those featured in this book are Velázquez’s Las Meninas and Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio, as well as such masterpieces as the 1665 self-portrait by Rembrandt at London’s Kenwood House, a painting seemingly devoid of any agenda other than what it feels like to carry into old age the weight of being human. Yet despite such riches, this genre has, until now, remained largely overlooked (Laura Cumming’s recent book, A Face to the World, is an exception), existing merely as subset within portraiture, which is a relatively under-investigated subject. Perhaps the huge diversity within self-portraiture, and its leaning towards bombast, have kept scholars at bay.

(Image: detail from Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment via Wikimedia Commons)

How Inequality Damages The Wealthy

David Lay Williams, author of Rousseau’s Social Contract, explains what Rousseau had to say on the subject:

[P]erhaps the most pernicious effects of economic inequality, for Rousseau, are wrought on the soul. Tremendous wealth, on his reasoning, enfeebles the conscience. We social animals are always driven to distinguish ourselves, to prove ourselves better than others. This is not always socially destructive, insofar as distinction is granted for the right reasons – namely, civic and sociable behavior. Society, however, has increasingly not only rewarded distinction with wealth, but made wealth a distinction worthy of respect. Where this happens, one’s status owes not just to one’s wealth per se, but to one’s wealth relative to the poverty of others. Rousseau worried that in the most unequal societies, the rich would acquire a “pleasure of dominating” that renders them “like those ravenous wolves which once they have tasted human flesh scorn all other food, and from then on want only to devour men.” Against a mind degraded in this way, addicted to the pleasure of domination, no appeal to justice, fairness, or any other value we like to think defines us, can have any effect; and no just society can stand on such foundations.

What Your Beard Says About You (And Me)

Truth In Advocating

Dan Gillmor argues that the reporting of advocacy organizations is becoming more and more like real journalism:

Yes, BuzzFeed, Vox, and ESPN’s new FiveThirtyEight, and a host of other large and small new media operations are extending the news ecosystem. But so are Human Rights Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Cato Institute, and a host of other organizations that do serious reporting about some of the key issues of our time. The latter are doing advocacy journalism—coverage with a clearly stated worldview—and often leading the way for traditional journalists.

In my most recent book I called them “almost-journalists,” because I believe that advocates’ media work doesn’t always take note of opposing alternative viewpoints and facts. At this point, I’m ready to drop the “almost” part of the expression. I’m not saying they’re doing journalism of the type that rose to prominence in American newspapers in the second half of the 20th century—the by-the-numbers, “objective” coverage that still can serve a valuable purpose. Rather, they’re going deeper than anyone else on topics that they care about that are vital for the public to understand, but which traditional journalists have either ignored or treated shallowly. Then they’re telling us what they’ve learned, using the tools and techniques of 21st-century media.

Hyperactive Prescribing?

Ryan D’Agostino worries ADHD is being over-diagnosed:

Falsely diagnosing a psychiatric disorder in a boy’s developing brain is a terrifying prospect.

You don’t have to be a parent to understand that. And yet it apparently happens all the time. “Kids who don’t meet our criteria for our ADHD research studies have the diagnosis—and are being treated for it,” says Dr. Steven Cuffe, chairman of the psychiatry department at the University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville and vice-chair of the child and adolescent psychiatry steering committee for the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.

The ADHD clinical-practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics—the document doctors are supposed to follow when diagnosing a disorder—state only that doctors should determine whether a patient’s symptoms are in line with the definition of ADHD in the DSM. To do this accurately requires days or even weeks of work, including multiple interviews with the child and his parents and reports from teachers, plus significant observation. And yet a 2011 study by the American Academy of Pediatrics found that one third of pediatrician visits last less than ten minutes. (Visits for the specific purpose of a psychosocial evaluation are around twenty minutes.) “A proper, well-done assessment cannot be done in ten or fifteen minutes,” says Ruth Hughes, a psychologist who is the CEO of Children and Adults with ADHD (CHADD), an advocacy group.

Only one significant study has ever been done to try to determine how many kids have been misdiagnosed with ADHD, and it was done more than twenty years ago.

Stinking Water

More than two months after the chemical spill that contaminated the tap water of more than 300,000 West Virginians, Marin Cogan finds that many don’t trust state officials’ assurances that the water is safe to use again:

Every morning before he leaves for work, [Robert Thaw] takes a wineglass and fills it with tap water. He dips his nose into the glass. “I can smell it right now,” he says. “It’s definitely there.”

Of all the barriers keeping people from trusting the water again, the smell might be the strongest. The scent still lingers around the site of Freedom Industries as though the spill had happened yesterday. This month, a study by scientists examining the impact of the spill showed that humans can detect the odor at an estimated .15 parts per billion—meaning that long after officials said it was safe, residents were still smelling it in their water. Robert likes to say that “humans did not make it this far eating and drinking things that don’t smell right.” They trust their noses over the government.

In a lengthy feature, Evan Osnos explores what the spill means for the politics of the coal industry:

By harnessing the most powerful technologies of political influence—campaign finance, public relations, politicized research—West Virginia’s coal industry has recast an economic debate as a cultural debate: a yes-or-no question, all or nothing. Viewed in that light, a vote for the industry is a vote for yourself, your identity, your survival. The coal industry has created the illusion of vitality. … The arguments for making sacrifices to protect the coal industry will become more difficult to sustain. With the most accessible seams depleted, and West Virginia coal facing competition from inexpensive natural gas, the U.S. Department of Energy forecasts that by the end of the decade coal production in the region will have dropped by half. In anticipation, the West Virginia Center for Budget and Policy, a progressive think tank, has called for using natural-resources taxes to create a “future fund” that would promote diversification by investing in infrastructure, education, and job-training programs.

The Death Penalty In Black And White

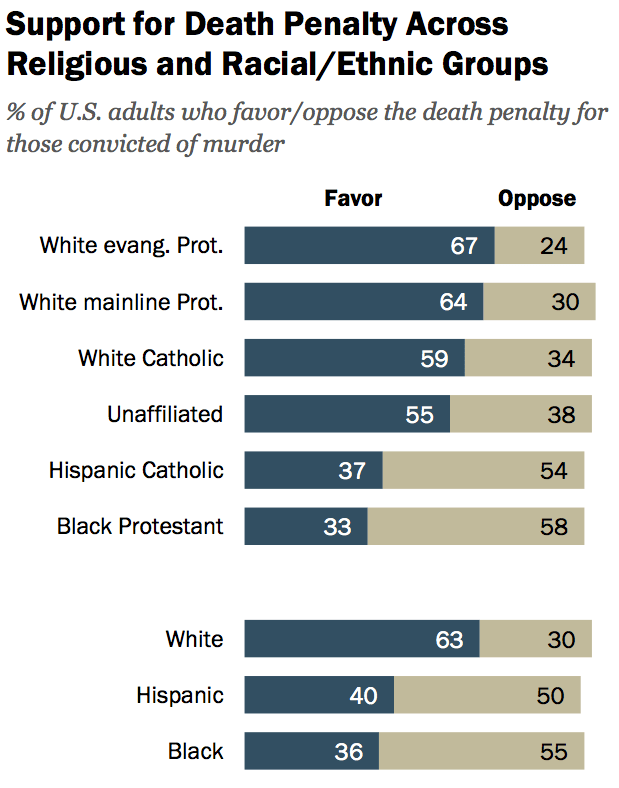

A Pew survey released on Friday found that capital punishment is becoming less popular:

55% of U.S. adults say they favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. A significant minority (37%) oppose the practice. While a majority of U.S. adults still support the death penalty, public opinion in favor of capital punishment has seen a modest decline since November 2011, the last time Pew Research asked the question. In 2011, fully six-in-ten U.S. adults (62%) favored the death penalty for murder convictions, and 31% opposed it.

Bouie examines the racial divide illustrated in the above chart:

Our cultural attitudes are unconsciously shaped by our collective history as much as they are consciously shaped by our current context. When you consider the death penalty as a tool of racial control—a way for whites to “defend” themselves from blacks—then Pew’s poll results make sense. What we’re looking at is the inevitable result of that history expressed through public opinion, and influenced by racialized ideas on crime and criminality.

If you’re still skeptical, consider this: In 2007, two researchers tried to gauge racial differences on capital punishment and assess how blacks and whites responded to arguments against the practice. Their core findings with black Americans weren’t a surprise—in general, blacks were receptive to any argument against the death penalty.

Their findings with whites, on the other hand, were disturbing. Not only where whites immune to persuasion on the death penalty, but when researchers told them of the racial disparity—that blacks faced unfair treatment—many increased their support.

But Andrew Gelman disputes Bouie’s conclusion that white support for executions is all due to racism:

He’s attributing the difference in attitudes to historical racism among white southerners. But the gap in attitudes has increased during recent decades, when racism has declined. Whites have become more politically conservative, but that’s not the same as becoming more racist. To accept my argument, you don’t need to believe that there is no racism among American whites. All you have to accept is that white racism is much lower than it was in the 1950s, which seems clear enough to me, given survey evidence on direct questions about racism.

Meanwhile, looking at the lower rates of support among younger Americans, Allahpundit wonders whether public opinion is turning against capital punishment for good:

Whether this is now a fixed star in millennials’ liberal-ish ideology or a simple reaction to the fact that they’ve grown up in a safer America, which could change if/when the crime rate does, is obviously unclear.

Wit Around The World

In another installment of Slate‘s series on humor, Peter McGraw and Joel Warner look at what inspires laughter in different countries:

Some cultures have diverse brands of comedy while other societies’ humor is remarkably uniform. When we traveled to Japan, immersing ourselves in sadistic game shows, ribald karaoke excursions, and the (mandatory!) comedy training schools for aspiring comedians, we hardly understood any of the jokes. That’s because most of them didn’t bother with set-ups at all. As a member of the Japanese Humor and Laughter Society explained to us, Japan is a high-context society: It is so homogenous, jokesters don’t need to bother with explanations or detailed backstories. They can get right to the punch line. One common joke, about an Olympic gymnast whose leotard was hiked embarrassingly high during a performance, has apparently become so familiar that even the punch line isn’t necessary. All you have to do is gesture to your upper thigh.

A newer piece from the series tackles whether jokes can propel political change:

If anyone was going to argue that such witticisms helped topple the Berlin Wall, it would be British sociologist and international joke expert Christie Davies, who spent decades tracking humor in the USSR. But in fact, he believes the opposite. According to Davies, among all the factors that led to the Soviet Union’s spectacular collapse, joking didn’t even crack the top 20. At best, he thinks the explosion of Soviet jokes was an indication of a rising political discontent already underway among the populace, not the spark that started the fire. Or as he puts it, “Jokes are a thermometer, not a thermostat.”

Some scholars go further, arguing that not only is comedy incapable of launching revolutions, but it might even have prevented a few from happening. According to this line of thinking, joking among the discontent masses might act as a release, allowing folks to let off steam, instead of rising up in rebellion.

Emerging, But Not Engaging

Analyzing the breakdown of last week’s UN vote to condemn Russia for violating Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Matt Ford notices that most of the world’s rising stars abstained:

Four of the five BRICS countries—Brazil, India, China, and South Africa—chose to not take a side on the resolution, as did many African, South American, and Asian countries. Some observers argue that the abstentions show a wariness among developing nations to choose sides in a confrontation between Russia and the West. “India and China have deep reservations on sovereignty and territorial integrity and in the past have not hesitated to slam US for Libya, Syria etc.,” wrote The Times of India after the vote. “With Russia doing exactly the same thing, the dilemma in the developing world is acute.” Other countries avoided participating in the vote altogether, including Iran, one of Russia’s closest allies, and Israel, one of America’s.

Suzanne Nossel argues that Obama should work on turning emerging democratic powers into anti-Putin allies:

India and Indonesia, respectively, are the world’s first and third most populous democracies, and they are centerpieces of Washington’s “pivot to Asia” and approach to handling China’s rise. Brazil and Argentina are the most influential players in Washington’s near abroad, and South Africa and Nigeria are key to countering terrorism and fostering trade and development across Africa. Reflecting their importance, the Obama administration has included these countries in an array of treaties, strategic dialogues, and commissions all aimed at improving relations — partly as a counterweight to China and Russia. …

In the drama over Ukraine and Russia’s relationship to the West, the supporting actors could ultimately matter nearly as much as the stars. Russia is boasting that it will survive the West’s sanctions because it has alternative trading partners. Having been blacklisted by the West, Putin will either be left friendless or will succeed in turning the BRICS, a coalition of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, into a tight new clique. These countries’ warmth toward him may affect his calculus on whether to push further on eastern Ukraine or call it a day with Crimea.