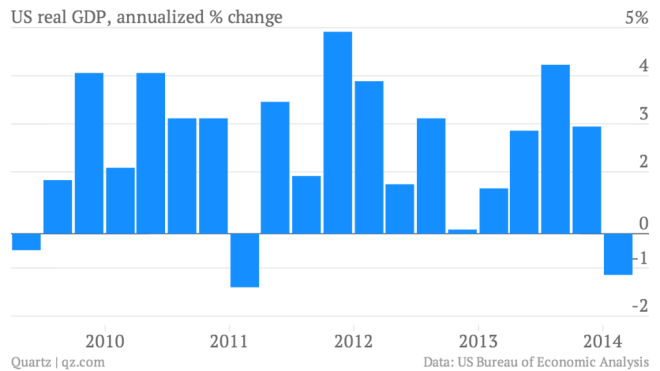

First quarter GDP slowed at an annual rate of -1.0% — worse than the initial estimate of 0.1% growth. It’s the first time since early 2011 that the economy has shrunk, mostly due to business inventories, construction and exports last quarter. Consumer spending actually rose by 3.1%, bolstered by strong health-care spending.

Ylan Q. Mui adds:

Businesses depleted their inventories and cut back on investment in the first three months of the year, while harsh winter weather curtailed construction. … The decline highlights the fragility of the nation’s recovery but is not likely to derail it altogether. Several forecasts for the current quarter show the economy growing at a healthy 3 percent annual rate or faster.

Matt Philips, who provides the above chart, finds that the markets are unfazed:

And that’s as it should be. For one thing, this is old news. Everyone already knew, from a string of previous data, that a brutal stretch of bad weather had hit consumption and other bits of the economy. And the fact that people stayed home to keep warm for the first three months means there’s a bunch of pent-up demand that should bolster the economy going forward. We’re already seeing that play out in the US job market, which has posted employment growth of over 200,000 a month for the last three months. (In April the economy created a particularly peppy 288,000 jobs.)

Ben Casselman puts the report in context:

This kind of contraction isn’t unheard of, but it is unusual. This is just the 10th time since World War II that GDP growth has been negative outside of a recession. Three of those negative quarters immediately preceded recessions. (The National Bureau of Economic Research defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months.” A common rule of thumb is that a recession involves two consecutive quarters of economic contraction, although that isn’t part of NBER’s official definition and not all officially recognized recessions have met that test.)

McArdle sees this as “a sign of an economy that is still very weak”:

It has been six years since the financial crisis. Federal government spending is still around 21 percent of GDP, up from 19 percent in 2007, and the Federal Reserve still has a very expansive monetary policy. Under those circumstances, a quarter of negative growth is pretty unsettling.

The most recent jobs numbers are more encouraging — but not all that stellar this far away from the crash. Six years in, employment is barely back to where it was, which means that it hasn’t even kept pace with population growth.

Reihan joins the conversation:

The federal government is not directly responsible for the overall growth rate of the American economy, regardless of what politicians claim. It does, however, play a large role in creating the conditions for business enterprises to invest and grow. And it’s not doing its job well.

Daniel Gross examines the big picture:

We live in an age of long business cycles. The last two economic expansions lasted 73 months and 120 months, respectively. Within those long stretches of growth, there were quarters when the economy grew rapidly and quarters in which it shrank or flat-lined. A bar chart showing quarterly GDP growth resembles the teeth of a saw, not a picket fence. The key is to focus on the long-term. And the long-term trend of growth—unsatisfying, sub-par, sub-optimal, and insufficient growth—is still intact. Next week, the expansion will enter its 59th month since the end of the Great Recession.