“I feel comfortable with [Hillary Clinton] on foreign policy. If she pursues a policy which we think she will pursue, it’s something that might have been called neocon, but clearly her supporters are not going to call it that; they are going to call it something else,” – Robert Kagan, unrepentant architect of the catastrophe in Iraq, and unreconstructed neocon, on the potential to revive neoconservative global aggression under president Hillary Clinton.

Month: June 2014

American Fútbol, Ctd

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry sticks up for the American preference for calling it “soccer” rather than “football”:

I’m writing this post as a public service to point out the actual fact, which is that the word “soccer” is basically as old as the sport itself, and has impeccable English bona fides. Here’s the real story, as Wikipedia notes: soccer came into existence at around the same time as other forms of football, in particular rugby football. The sport therefore became referred to as “association football”, to differentiate it from rugby football. With their talent for abbreviation and metonymy, “association football” quickly became “soccer”, from the word “association”.

Call soccer whatever you like. But now you know that the word soccer has impeccable historical and European bona fides, and is not some navel-gazing American invention. It is absolutely proper to call soccer soccer. If anything, calling it “football” is the navel-gazing form, since it ignores other forms of football, whether NFL football or rugby football.

Uri Friedman digs deeper into the history of the term:

If the word “soccer” originated in England, why did it fall into disuse there and become dominant in the States?

To answer that question, [sports economist Stefan] Szymanski counted the frequency with which the words “football” and soccer” appeared in American and British news outlets as far back as 1900. What he found is fascinating: “Soccer” was a recognized term in Britain in the first half of the twentieth century, but it wasn’t widely used until after World War II, when it was in vogue (and interchangeable with “football” and other phrases like “soccer football”) for a couple decades, perhaps because of the influence of American troops stationed in Britain during the war and the allure of American culture in its aftermath. In the 1980s, however, Brits began rejecting the term, as soccer became a more popular sport in the United States.

In recent decades, “The penetration of the game into American culture, measured by the use of the name ‘soccer,’ has led to backlash against the use of the word in Britain, where it was once considered an innocuous alternative to the word ‘football,'” Szymanski explains.

Trolling Or Threatening?

That’s roughly the question at the heart of a new First Amendment case the Supreme Court is taking up in its October term:

The case, Elonis v. United States, which we’ve previously covered in some detail, has reached the nation’s high court on appeal, after the Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that defendant Anthony Elonis’ 2010 Facebook rants mentioning attacks on an elementary school, his estranged wife, and even law enforcement, constituted a “true threat” under First Amendment precedent. As such, the court upheld Elonis’ sentence and conviction. In his petition to the Supreme Court, Elonis’ counsel said the issue boils down to “whether a person can be convicted of the felony ‘speech crime’ of making a threat only if he subjectively intended to threaten another person or whether instead he can be convicted if he negligently misjudges how his words will be construed and a ‘reasonable person’ would deem them a threat.”

For example, in one such Facebook posting, about which Elonis has since argued that he lacked criminal intent, he wrote: “Do you know that it’s illegal for me to say I want to kill my wife? It’s illegal. It’s indirect criminal contempt. It’s one of the only sentences that I’m not allowed to say.”

Lithwick’s take:

This case is not only crucially important in that it will force the court to clarify its own “true threats” doctrine and finally apply it to social media to determine whether—as Justice Stephen Breyer has suggested—the whole world is a crowded theater.

But perhaps it’s even more important in pushing the conversation about law enforcement, prosecution, and threats to include a much more sophisticated understanding of the ways in which the Internet is not just a rally or a letter. As Amanda Hess has explained so powerfully, women experience threats on social media in ways that can have crippling economic and psychological effects. At the margins, this is a case about the line between first amendment performance art, fantasy violence, real threats—and real fear. In a world in which men and women find it nearly impossible to agree on what’s an idle threat and what’s a legitimate one, it’s also a case about where that line lies, or whether there can be one.

Alex Goldman ponders how the Internet has changed the way we interpret threatening speech:

The internet has, in a strange way, diluted the power of the death threat. In more heated, less moderated corners of the internet, death threats are as natural as breathing. While threats against the President tend to be investigated seriously, and depending on the venue, they can land people in disproportionate trouble, death threats have sort of become part of internet parlance. Don’t like the my political views? I’ll kill you. Don’t like my favorite sports team? I’ll kill you. Don’t like the latest DLC for Fallout 3? I’ll kill you. For better or worse, the context of a death threat is often used to gauge how seriously it should be taken.

How Obamacare Is Splitting Republicans

Senator David Vitter, who is running for governor in Louisiana, is flirting with Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion:

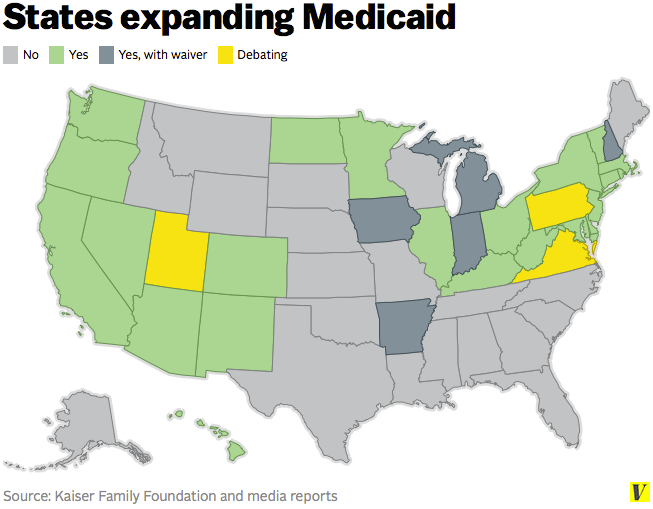

Republicans have found they have a good deal of leverage in using the Medicaid expansion to request state-based reforms, which require a federal waiver, from the expansion-supporting Obama administration. Arkansas pioneered the unique approach with a private option that uses Medicaid dollars to enroll people into private insurance plans through HealthCare.gov. Since then, Michigan, Iowa, Indiana, and New Hampshire have adopted their own reform-pegged expansions.

Whether Vitter actually becomes governor and manages to expand Medicaid is, of course, an open question. But at the very least his current support for a reform-based expansion shows the growing schism among Republicans about whether they should approve the Medicaid expansion

It’s worth noting that Vitter’s support of expansion is conditional:

In an email to The Wire a Vitter spokesperson wrote that any support of the expansion would depend on fixing the program: “The only way Senator Vitter would ever consider any expansion is if it fundamentally reformed the program, did not continue to drain state dollars way from higher ed, and did not provide additional disincentives for able-bodied folks to work, all factors he laid out clearly.”

Still, Igor Volsky sees Vitter’s maneuvering as part of a trend:

Vitter’s comments come as a growing number of Republicans are re-evaluating their opposition to Medicaid expansion. In May, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnnell (R-KY) expressed support for growing Medicaid by arguing that the process could be controlled by the state. Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R), a possible 2016 presidential candidate, has also announced that he would apply for a waiver that would allow Indiana to provide private coverage to its residents using funding secured by the Affordable Care Act. In total, nine Republican governors have backed Medicaid expansion, and the provision is also being embraced by vulnerable Democrats up for re-election, including Louisiana’s Mary Landrieu (D) and North Carolina’s Kay Hagan (D).

Beutler makes similar points:

[Vitter is] no stranger to the scatter-rightward impulse. But he’s also seen Louisiana’s unpopular current governor Bobby Jindal struggle with the absolutist position on Obamacare, and wants to replace Jindal who’s up against a term limit in 2015. So Vitter’s is actually triangulating against the current governor—banking against the possibility that some other hardliner will outmaneuver him. Vitter still boasts of his efforts to repeal Obamacare on his Senate website. But running anti-Medicaid expansion isn’t good politics. Even in Louisiana.

This kind of doublespeak isn’t new. But as Affordable Care Act enrollment inches toward 9 million, skeptical carriers announce that they’ll enter the marketplaces next year, and others announce nominal premium hikes, it’s becoming common in more and more conservative states.

Our Little Lie Detectors

Ryan Jacobs reviews research that suggests kids know how to spot a liar:

Studies have already shown that kids work as incredibly precise detectors of straight-up lies. Outside the realm of bold-faced falsehoods, though, children perform quite brilliantly, too. Subtler and more elegant deceit—the kind where the truth is told but other important elements are shaded or concealed—doesn’t go unnoticed by six-year-olds either, according to a new study published in Cognition. Unbeknownst to their teachers and parents, young kids are apparently equipped with the perceptive powers of seasoned Cold War spies. The new paper suggests that they don’t appreciate when they’re being misled with lies of omission and even adjust their behavior based on a previous record of deceit.

Eliana Dockterman explains how the experiments worked:

Researchers at MIT studied how 42 six and seven-year-olds evaluated information. … [T]he children were separated into two groups: one group got a toy that had four buttons, each of which performed a different function—lights, a windup mechanism, etc.; the other group got a toy that looked the same but only had one button, which activated the windup mechanism.

After the two groups of children had played with their respective toys, the researchers put on a show: a teacher puppet taught a student puppet how to use the toy, but only showed the student puppet the windup function. For the kids playing with the one-button toy, this was all the information; but for the kids playing with the four-button toy, the teacher puppet had left out crucial information. The researchers then asked all the children to rate the teacher puppet in terms of how helpful it was on a scale from 1 to 20. The kids with the multi-functional toy noticed that the puppet hadn’t told them the whole story and gave it a lower score than the children with the single-function toys did.

Privatize The VA?

A bill to reform the department, which passed the Senate in a nearly unanimous vote last week, would allow veterans facing long wait times at VA facilities to seek out care from private local doctors instead. However, it would also more than double the VA’s annual healthcare spending:

The analysis from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget suggests that providing VA-reimbursed private care to veterans, without setting budgetary caps and oversight, could explode the VA’s health-care budget with an additional $500 billion in spending over the next 10 years. … That’s more expensive than the entirety of Medicare Part D, which funds prescription drugs for seniors.

Patrick Brennan pans the reform as expensive and unnecessary:

The VA scandals demand an immediate response, of course, but the Senate bill isn’t necessary to execute it: President Obama has already ordered that the VA expand the coverage it offers outside the system for vets waiting for care. No program like this should be passed as an emergency measure.

Fixing the VA’s problems, such as they are, may require lots and lots of money — and maybe the Senate wasn’t voting to spend quite as much money as the CBO just said. But any congressman with any respect whatsoever for the concept of fiscal responsibility — not deficit hawks, just anyone concerned with how much we spend and on what — should want Congress to take time to study this issue (as, indeed, the House is planning to).

Danny Vinik calls it a “Trojan horse” for privatization:

The reason that clinics and hospitals—at both VA and non-VA facilities—have such long wait-times is a shortage of primary care doctors. This shortage has happened for a number of reasons: Medical students face financial incentives to choose a specialty field instead of becoming a primary care doctor. State occupational licensing laws prevent nurse practitioners from performing many straightforward medical tasks. Medical schools receive billions in federal funding with little oversight for how may primary care doctors they produce. The bills’ partial privatization scheme does nothing to ease these problems.

But Kevin Drum sees it as an opportunity to finally resolve the question of whether privatization actually works or not:

Maybe this is a good thing. Better access to health care means more people will sign up for health care, and they’ll do it via private providers. That’s the basic idea behind Obamacare, after all.

Of course, it’s also possible that this might be a bad thing. As Phil Longman points out, outsourced care lacks the very thing that makes VA care so effective: “an integrated, evidence-based, health care delivery system platform that is aligned with the interests of its patients.” …

So which is it? Beats me. That’s why I sure hope someone is authorizing some money to study this from the start. It’s a great opportunity to compare public and private health care on metrics of both quality and cost. It’s not a perfect RCT, but it’s fairly close, since the people who qualify for private care are a fairly random subsegment of the entire VA population. If we study their outcomes over the next few years, we could learn a lot.

Michael Cannon and Christopher Preble would prefer to do away with the separate VA health system entirely:

We propose a system of veterans’ benefits that would be funded by Congress in advance. It would allow veterans to purchase life, disability and health insurance from private insurers. Those policies would cover losses related to their term of service, and would pay benefits when they left active duty through the remainder of their lives. To cover the cost, military personnel would receive additional pay sufficient to purchase a statutorily defined package of benefits at actuarially fair rates. The precise amount would be determined with reference to premiums quoted by competing insurers, and would vary with the risks posed by particular military jobs.

Insurers and providers would be more responsive because veterans could fire them — something they cannot do to the Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ insurance premiums would also reveal, and enable recruits and active-duty personnel to compare, the risks posed by various military jobs and career paths. Most important, under this system, when a military conflict increases the risk to life and limb, insurers would adjust veterans’ insurance premiums upward, and Congress would have to increase military pay immediately to enable military personnel to cover those added costs.

Graduating Summa Cum Latte

Starbucks will help employees attend online courses at Arizona State:

The plan comes with a few caveats, according to The New York Times: employees must work at least 20 hours per week at Starbucks and meet admission criteria for ASU. The online program at ASU admission requirements are the same as general admission, with average SAT reading and math scores of 508 and 491, respectively, an ACT score of 22, and a high school GPA of at least 3.0 necessary for acceptance.

While restricting this plan to one school might seem limiting, the Arizona State online program is a pretty good one. U.S. News ranks ASU’s the ninth-best online bachelor’s program in the country. Nearly 200 of the school’s full-time faculty teach courses available online (the average teaching experience for online instructors is seven years), the program has a retention rate of roughly 80 percent, and a little more than one-third graduate in three years.

The Bloomberg editors are pleased with the new tuition scheme:

What makes this different from other companies’ tuition-support programs is that employees don’t have to stay at Starbucks after they graduate. Nor is the benefit limited to long-serving workers; anyone can take advantage of them, regardless of how long he or she has been with the company. And there are about 40 programs to choose from.

Danielle Kurtzleben believes it’s a pretty good deal for Starbucks:

Starbucks’ new program isn’t about altruism. Research shows educational reimbursement can have big benefits for employers. One issue is taxes. The first $5,250 in tuition benefits accrue to workers tax-free, making tuition payments a way to get more bang for your compensation buck. (That said, a Starbucks spokesperson told the Chronicle of Higher Education that the “vast majority” of workers won’t hit the $5,250 threshold.)

But another issue is that different employees will value a tuition benefit differently, and tuition assistance might disproportionately appeal to higher-quality workers. In a 2002 NBER working paper, Wharton School of Business Professor Peter Cappelli studied Census data and found that employees who use tuition assistance are more productive than their peers. In addition, those extra abilities are not readily visible to most other employers who are competing for talent; the very act of offering tuition assistance draws in people with those higher abilities. An employer doesn’t have to go looking for them.

But Andy Thomason urges baristas to check the fine print:

Participating employees will get reimbursed only for every 21 credits they complete (the equivalent of about seven courses) and only after the fact. Starbucks says the rule is meant to encourage completion, rather than having employees sporadically take a handful of classes. But for someone living off a barista’s wages, that’s a pretty hefty chunk to pay upfront.

And Rachel Fishman argues that, “like many ‘free college’ programs, this benefit comes with a lot of strings attached”:

In this situation, the student picks up the tab first, and then if they are successful Starbucks will pay the student back. Removed from the equation is the institution. ASU Online is an expensive school. At approximately $15,000 a year for tuition and fees alone, the price is more than four times the price of an average community college ($3,264) and a little less than double the average in-state tuition rate of $8,893. Undoubtedly, this program will benefit some of Starbucks’ 135,000 employees. But anyone who thinks this may be an innovative solution to the college cost problem is mistaken.

Related thread on tuition costs here.

The View From Your Window

Gold Stars For Teachers

Adam Ozimek argues that educators get more love than many realize:

The truth is that teaching is still a highly respected career, and we still lionize teachers in this country. One piece of evidence for this comes from a Harris Interactive poll that has asked the following question sporadically from 1977 to 2009:

I am going to read off a number of different occupations. For each, would you tell me if you feel it is an occupation of very great prestige, considerable prestige, some prestige or hardly any prestige at all?

So how do you think teachers have faired on this survey? It turns out the do quite well. As of 2009, 51 percent of respondents thought teachers had “very great prestige” and another 22 percent thought they had considerable prestige. This is compared to 17 percent and 22 percent for journalists, and 44 percent and 24 percent for police. Judging by the “very great prestige” percentage, teachers rank 6th under firefighters, scientists, doctors, nurse, and military officer. Only 10 percent of individuals thought teachers had hardly any prestige at all.

Freddie counters that while the American public may hold teachers high in esteem, the country’s elites do not:

Ozimek has repeatedly denied to me that the Ivy League striver types that are at the pinnacle of American aspirational culture have a low view of teaching as a profession. But we can let the people within those institutions speak for themselves. Harvard Graduate School of Education Dean James Ryan — who, I presume, Ozimek would recognize as knowledgeable on this topic – says that only a minuscule percentage of Harvard students study education, despite the fact that almost 20 percent of Harvard students apply for Teach for America. And Walter Isaacson, who as president of the Aspen Institute has plenty of exposure to both educational research and elite culture, is quoted as saying there’s a perception that “it’s beneath the dignity of an Ivy League school to train teachers.” That’s reflected in institutional behavior: Cornell has stopped providing undergraduate teacher training. That actual institutional behavior tells us far more about what elites think of teaching than polling could.

Don’t Blow A Fuse Over That Soccer Game

The US beat Ghana 2-1 in their first round World Cup match yesterday. Hard luck for Ghana, which had rationed electricity to make sure everyone could watch the match on TV:

Ghana has been suffering from a power shortage this year due to low water levels at hydroelectric dams on the Volta River. The nation’s utilities regulator is already rationing electricity by mandating sporadic shutdowns. To ensure World Cup viewing won’t be interrupted, Ghana is purchasing 50 megawatts of electricity from its neighbor, Ivory Coast. Power plants will also be running at maximum capacity, and Volta Aluminum, the nation’s largest smelter and a large drain on electricity, will slow production during the match.

Plumer takes the opportunity to point out that “access to electricity is a hugely pressing concern throughout Africa”:

Ghana is actually one of the luckier countries on this score — roughly 72 percent of its population has access to electricity, however unreliable. In neighboring Ivory Coast, by contrast, it’s 59 percent. In Tanzania, only 15 percent of people have reliable access to electricity. Add it all up, and some 590 million people across sub-Saharan Africa don’t have any power at all. Among other things, that’s a major public-health issue: Without electricity, many households turn to wood stoves, whose indoor pollution now kills 4.3 million people per year (worldwide), more than AIDS and malaria combined.

(Chart from Todd Moss)