In a review of MoMa’s Gauguin exhibit, Daniel Goodman contemplates the painter’s religious influences:

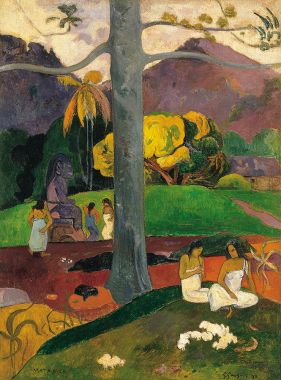

In Mata Mua, Tahitian women dance, play instruments, and worship a statue of Hina, the Tahitian moon goddess. The women frolic in a lush, idyllic landscape  in the foreground, while purple mountains protruding out of an off-white sky loom over them in the background, and a large cross-shaped bluish-gray tree (the Tree of Life in this Tahitian Eden?) centers the canvas. What may be most interesting about Mata Mua is that, even though the Polynesian religious ritual is the central subject matter, Gauguin limits the scene to the left corner of the painting and places the cross-shaped tree squarely in the center, subtly reminding us of Gauguin’s abiding interest in Christianity.

in the foreground, while purple mountains protruding out of an off-white sky loom over them in the background, and a large cross-shaped bluish-gray tree (the Tree of Life in this Tahitian Eden?) centers the canvas. What may be most interesting about Mata Mua is that, even though the Polynesian religious ritual is the central subject matter, Gauguin limits the scene to the left corner of the painting and places the cross-shaped tree squarely in the center, subtly reminding us of Gauguin’s abiding interest in Christianity.

In fact, despite his fascination with Polynesian religion, and his dissatisfaction with Roman Catholic doctrine and institutional religion, Gauguin remained interested in Christianity and the Bible. … Of course, Gauguin experienced his own paradise lost when he arrived in Tahiti and discovered that it was not the unspoiled paradise of his imagination. Many of his paintings depict not what he actually saw but what he had wanted to see. Mata Mua is Gauguin’s vision of paradise. He created the pristine world he wanted to experience, rather than the fallen one he had to experience. It’s a “romantic, idealized, but ultimately false” vision of Tahiti, say the MoMA curators; but though Gauguin’s vision of Tahiti was objectively false, it was entirely true in the realm of Gauguin’s imagination. And from the perspective of artistic surrealism, nothing could have been truer than Gauguin’s Tahitian Eden.

Update from a reader:

Left unmentioned in the discussion of Gauguin’s, “Tahitian Eden,” is his well-documented pursuit and abuse of underage Polynesian girls.

During a brief stay on Hiva Oa (I was trapped there for two weeks in 2003 after quite literally jumping ship), it is common knowledge that the nuns in charge of the local girls school were forced to take drastic measures to keep the artist (who is buried on the island) away from the children. Alas, Gauguin eventually ‘married’ three of the local girls, all between the age of 13 and 14.

Gauguin was (and is) widely recognized as a pederast and sexual libertine. Frankly, I find Goodman’s reflection on the, “pristine world he wanted to experience, rather than the fallen one he had to experience,” to be sad and hysterical in its wrongness.

Another also doesn’t see paradise:

I’m neither an art historian nor an art critic, so if an expert says the Gauguin painting is supposed to be idyllic or some kind of Eden, then I’m inclined to try to see what they mean. But I have to say that I laughed out loud when I looked at the paintings and then read the Gauguin interpretations. When I see the painting, I definitely do not see a happy place, much less an Eden. That painting is creepy. What’s with all the dark and muddy colors? To me, people think it’s a kind of Eden because you look at the women in white right away. But look around them and at everything else. What’s with the dude walking toward the two women dancing by the statue? Does he have his hand behind his back? Is he carrying a knife? Maybe that’s why the tree is sorta shaped like a crucifix, the Christian symbol of sacrifice. The creepy vines curl near the women in white. What exactly is surrounding them? The woods in the background are also ominously dark and the bright yellow tree in the background gets less so one the left side of the tree, almost like it’s curling around the tree to look. I look at this painting and think, this is a place of terror.

(Image: Mata Mua by Pual Gauguin, 1892, via Wikimedia Commons)