Pointing to a new study showing that income inequality is rapidly declining at the global level, Tyler Cowen argues that the redistribution favored by egalitarian movements in the US would end up hurting international prosperity:

Although significant economic problems remain, we have been living in equalizing times for the world — a change that has been largely for the good. That may not make for convincing sloganeering, but it’s the truth. … Many egalitarians push for policies to redistribute some income within nations, including the United States. That’s worth considering, but with a cautionary note. Such initiatives will prove more beneficial on the global level if there is more wealth to redistribute. In the United States, greater wealth would maintain the nation’s ability to invest abroad, buy foreign products, absorb immigrants and generate innovation, with significant benefit for global income and equality.

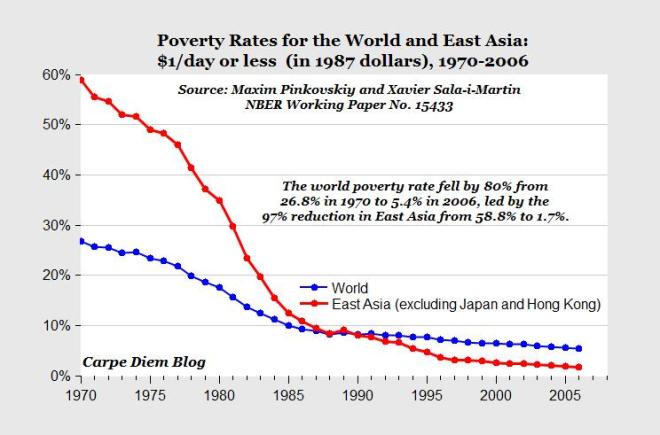

Mark Perry backs up Cowen’s thesis with the above chart. But Daniel Little criticizes Cowen’s “Panglossian” picture of global inequality:

Cowen bases his case on what seems on its face paradoxical but is in fact correct: it is possible for a set of 100 countries to each experience increasing income inequality and yet the aggregate of those populations to experience falling inequality. And this is precisely what he thinks is happening.

Incomes in (some of) the poorest countries are rising, and the gap between the top and the bottom has fallen. So the gap between the richest and the poorest citizens of planet Earth has declined. The economic growth in developing countries in the past twenty years, principally China, has led to rapid per capita growth in several of those countries. This helps the distribution of income globally — even as it worsens China’s income distribution.

But this isn’t what most people are concerned about when they express criticisms of rising inequalities, either nationally or internationally. They are concerned about the fact that our economies have very systematically increased the percentage of income and wealth flowing to the top 1, 5, and 10 percent, while allowing the bottom 40% to stagnate. And this concentration of wealth and income is widespread across the globe.

Ryan Avent pushes back as well:

There is an alternative hypothesis, however, which Mr Cowen mostly disregards: that redistribution provides insurance against economic dislocation and therefore softens resistance to globalisation. It’s worth pointing out that the world has experienced two great eras of globalisation. The first combined minimal redistribution with minimal political power for non-elites. The second combined universal suffrage with substantial redistribution. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to conclude that redistribution is the price democracies pay for globalisation.

And that makes perfect sense! Reducing barriers to trade generates net gains, but those gains will occasionally be distributed in highly unequal fashion. If gains are concentrated and no provision is made for redistribution, then a voting majority might well conclude that openness is a losing proposition. Mr Cowen seems to want voters to recognise that whether or not they personally are made better off by globalisation it is a good thing to support, because it enables the enrichment of poor areas of the globe. But few voters are content to have their economies run as charities (and a good thing for economists that they aren’t, as that would make a baseline assumption of rational self-interest look pretty absurd).