by Bill McKibben

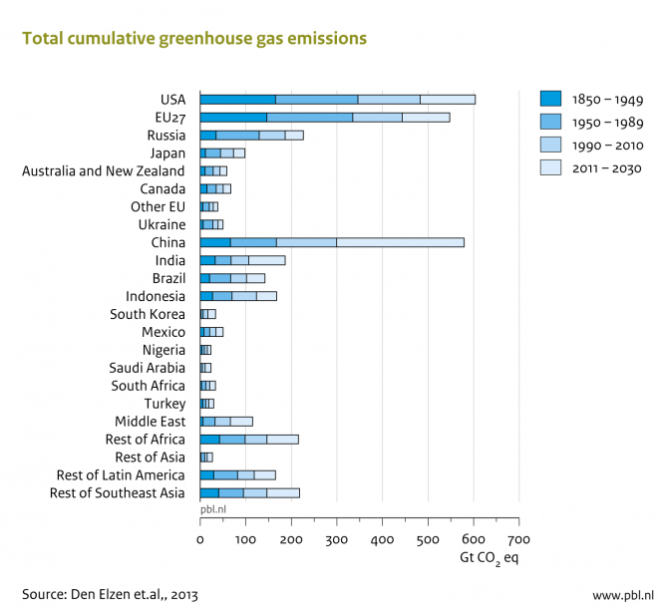

Earlier today I went after libertarians for their troubles with climate change. But it’s conservatives in general that have been the real hypocrites here, given that the least conservative thing you can possibly imagine would be running the temperature of the earth way out of the range where human civilization has previously thrived. And the irony is, some of the most obvious ways out are… kinda conservative. Or at least should appeal to conservatives who are not, in reality, shills for the fossil fuel industry. Yes, given that we’ve delayed as long as we have we need a big government effort to put in renewable energy, and yes we need wholesale shifts in who holds power (the key new text on climate change will be Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, due for release next month). We also need to provide massive aid for the countries we’ve endangered by our unchecked carbon emissions. But one of the big changes we require is remarkably conservative in nature.

It’s called Cap and Dividend, long proposed in one form or another by the great climate scientist James Hansen and by an excellent advocacy group called the Citizens Climate Lobby. It derives from the work of Peter Barnes, who has a fine new book called With Liberty and Dividends for All. Let today’s Washington Post editorial page explain:

A prominent member of Congress has proposed a comprehensive national climate-change plan. It’s only 28 pages long, it’s market-based, and it would put money into the pockets of most Americans.

His proposal would put a limit on the country’s greenhouse-gas emissions, a cap that would decline each year. Beneath that cap, companies would have to buy permits for the emissions their fuels produce. The buying and selling of permits would set a market price for carbon dioxide. The government would rebate all of the revenue from selling permits back to anyone with a Social Security number,more than offsetting any rise in consumer prices for 80 percent of Americans. Most upper-income people, who use more energy, and government, which would get no rebate, would pay more under the plan.

Every time you ratcheted down the cap on carbon (in order to keep the planet from being wrecked, which would be… expensive) the dividend check would rise; therefore there’d be far less political opposition to doing the right thing. And this plan posits a different understanding of the world: if anyone owns the atmosphere, it’s us, not Exxon. Since the fossil fuel industry currently gets to use the atmosphere as a free dump, there will doubtless be opposition from the likes of the Kochs. But this is a sensible, straightforward plan.