Bill McBride analyzes today’s jobs report:

This was a solid report with 248,000 jobs added and combined upward revisions to July and August of 69,000. As always we shouldn’t read too much into one month of data, but at the current pace (through September), the economy will add 2.72 million jobs this year (2.64 million private sector jobs). Right now 2014 is on pace to be the best year for both total and private sector job growth since 1999.

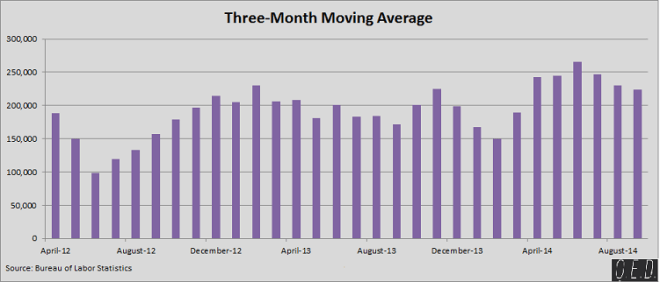

Vinik recommends looking at the three month moving average (above), which shows that “the economy certainly has strengthened over the past six months and is in better shape.” But he also spotlights the “one glaring sign that there is still slack in the labor market: wages are stagnant”:

In September, wages grew 0.0 percent, below expectations of 0.2 percent. Over the past year, wages have grown just 2.0 percent, barely keeping up with inflation. Wages will rise when employers have to compete for scarce labor—i.e. when the economy is at or near full employment. That clearly isn’t the case right now, meaning the 5.9 percent unemployment rate doesn’t represent the current state of the labor market. If the Fed were to raise interest rates, it would choke off the recovery and prevent any wage growth.

Annie Lowrey finds that “Jobs Day has become less and less of a tentpole event in the economic data calendar”:

In part, that is because the story of the recovery has become static: It just keeps chugging along at the same decent-enough pace. It is also because the unemployment rate — the headline number in the jobs report — has started telling us less and less about the state of the economy.

She adds that a “broader set of indicators generally gives a dimmer view of the economy — and that remains true this month, good headline number aside”:

So applaud this jobs report. It’s a legitimately good one. But do not let it change your view of the economy too much. Growth might be accelerating, but the underlying story of the recovery is not changing. For tens of millions of families, that unemployment rate is nothing but a number.

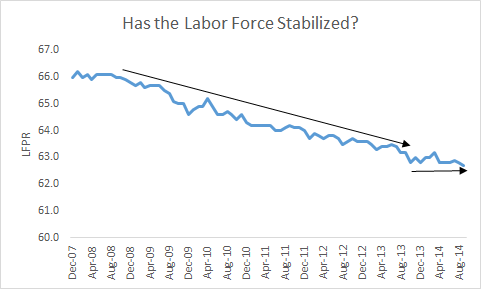

Jared Bernstein focuses on the participation rate:

The labor force participation rate (LFPR)—the share of the 16 and up population either working or looking for work—is a key variable to watch these days. It ticked down slight last month, as noted, but as shown in the chart, has generally stabilized over the past year. This has two important implications.

Source: BLS

First, it suggests a strengthening job market as part of the decline in the LFPR over the recession and weak recovery was due to discouraged job seekers giving up hope. Second, as noted above, it means that recent declines in the jobless rate are due to more people getting jobs versus giving up the search.

Ben Leubsdorf plucks out other key numbers from today’s report. One that shouldn’t be overlooked:

The number of workers who have been unemployed for more than six months has declined over the last year by 1.2 million. But 3 million strong in September, they still made up 31.9% of all unemployed Americans.

And Kilgore asks, “will it matter politically?”

It’s unlikely. As Dave Weigel points out, at this point in 2006, just prior to a Democratic midterm landslide, the unemployment rate was under 5% and net job growth was steady if not spectacular.