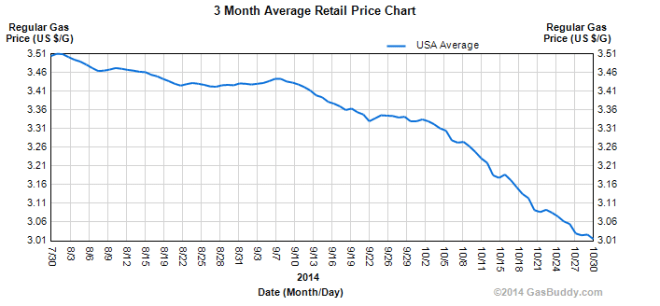

Mataconis argues that overall, the ongoing decline in oil prices is a boon to the US and other advanced industrial nations:

Falling prices for oil will eventually filter through to the prices of the products derived from oil itself, including not only gasoline but also home heating oil and jet fuel. In the short and medium term, this would provide some relief for consumers and for companies that depend on transportation such as Wal-Mart, Amazon, airlines, and shippers such as UPS and Fed-Ex. If prices continue to fall, those benefits will become more apparent and could help to boost economic growth at least slightly, which would be good news for the jobs market and even tax revenues and the Federal Budget Deficit. Other nations that are oil dependent would likely experience similar benefits, which would be good news for areas like Europe where the economy seems to be slowing down a bit and for the world as a whole, which in turn would be good news for nations that are dependent on international trade, which is pretty much every major industrialized nation at this point.

Derek Thompson, who believes prices might fall even further, points out that some industries and regions will be hurt even as consumers celebrate:

It’s hard to say how the sliding price of gas will affect the United States, as a whole, because the economy is a messy mix of cities, industries, and consumers behaviors, each of which experience falling prices differently. In cities with lots of driving and not much energy production—e.g. throughout California—cheaper gas is simply good, the end. Three-buck gasoline gives back as much as $500 a year to the typical family with two cars, compared to the $4.50 gallons from a few years ago. But mining and energy jobs have been the fastest-growing sector of the labor market, and thinner profits for energy producers will hurt states like North Dakota and New Mexico, who have relied on energy exports to pay for new jobs and higher wages.

Jared Gilmour posits that the falling prices are “threatening to make costly US shale extraction uneconomic”:

Limited pipeline capacity and overproduction of natural gas in the Marcellus shale has pushed prices down, making it hard for producers to turn a profit. Drillers are taking on ever increasing amounts of debt to finance their operations. And there may not be as much shale oil and gas as the US government forecasts, according to a new report from the Post Carbon Institute, a California-based think tank that promotes sustainable energy. “Shale will be robust for the next four or five years, but because of declines at the well-level and field-level, it’s not sustainable in the medium and longer term,” says study author David Hughes in a telephone interview Tuesday. “Policymakers should be aware of that before they try to cash in on a bounty that may not exist ten or fifteen years down the road.”

But industry experts tell the WSJ that prices would have to fall quite a bit farther to endanger the shale industry:

Marianne Kah, chief economist of ConocoPhillips , said oil prices would need to fall to $50 a barrel “to really harm oil production” in U.S. shale basins. She said 80% of the American shale sector—in which ConocoPhillips is a major operator—is profitable at prices between $40 and $80 a barrel for benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude. Jason Bordoff, director of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, said he believed prices would have to fall much further to put significant pressure on the U.S. energy boom. “I am not sure if $80 is enough,” he said. “You might need $60 or $65 to really see a stress test.”

(Chart via GasBuddy.com)