Jesse Singal flags a new study on the question:

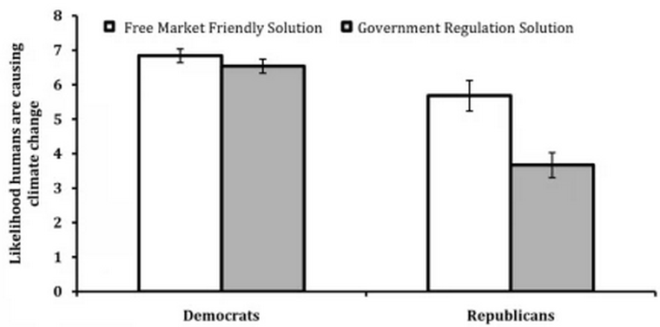

The basic idea here is that people are less likely to believe that something’s a problem if they have “an aversion to the solutions associated with the problem,” as the authors put it. Strictly speaking, this doesn’t make sense — when determining whether or not to believe in a problem, all that should matter is evidence for the existence of that problem. (Just because you believe it will be expensive to replace that leak in your roof shouldn’t make your belief in the leak any less likely.)

But it fits into a broader framework of what psychologists call “motivated reasoning” — the human tendency to form beliefs not based on a strictly “objective” reading of the facts, but in a way that offers some degree of psychological protection.

Chris Mooney chimes in:

[T]he new study has its weaknesses. For instance, we probably shouldn’t assume based on this paper that running out and singing the praises of clean energy and green tech, framed as a free-market solution, would actually work to depolarize the climate issue. Other research, for instance, implies that the issues of clean energy and energy efficiency have also become infected with partisan emotions, to a significant extent.

Still, it is very useful to bear in mind that often, when we appear to be debating science and facts, what we’re really disagreeing about is something very different.

Andrew Revkin draws “positive lessons” from the study:

As the “Six Americas” surveys run by the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication have shown, there’s plenty of common ground on energy innovation and incentives for efficiency, so it’s possible to have a constructive conversation on global warming science and at least some solutions across a range of ideologies. … And, of course, this doesn’t mean that those with strong views about the merits of a carbon tax or climate treaty or other solution involving strong governance should clam up. They just might do better by speaking in two sentences instead of trying to mash the science and a particular prescription into a single sound bite.