This week, the FDA released new rules on calorie labeling:

The changes are sweeping: Any restaurant with 20 or more locations, movie-theater chains, amusement parks, meals sold in grocery stores, and vending machines will all be required to label calorie amounts on food options. There is no exception for alcohol ordered from a menu (mixed drinks ordered at the bar, however, will continue to not have calorie information). The rules take effect a year from now, although vending machine operators will have two years to comply.

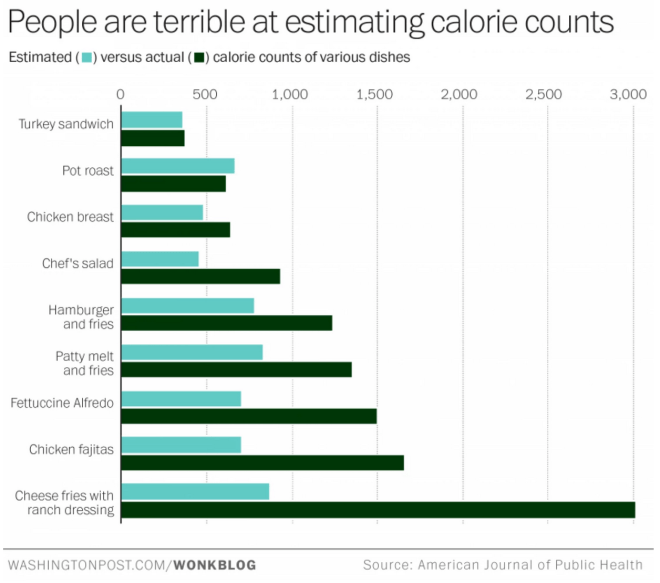

In response, Jason Millman highlights research on caloric ignorance, including the above chart:

Do people eat healthier when they can see calorie counts? The evidence so far seems mixed. The impact seems to be greater when the calorie count is much higher than what consumers expect. What does seem clear from past studies is that people really are terrible judges of how many calories they consume when they dine out.

Harvard Medical School researchers who polled more than 3,400 customers at fast food chains found that people significantly underestimated the calories in their meals. This varied by age group — adolescents on average underestimated calorie content by 259 calories, while adults and parents of school-age children underestimated by 175 calories. More than a quarter of people, though, underestimated calorie content by at least 500 calories, according to the research published in the British Medical Journal last year.

Danny Vinik explains why calorie counts might not alter food choices:

In 2013, researchers at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation put together a literature review of studies on menu labeling, in order to understand public opinion on menu labeling and the effectiveness on calorie counts. The idea itself turns out to be pretty popular. In the United States, for instance, nearly three-quarters of Americans support menu labeling. After New York required labels in 2008, 84 percent of residents said they found the labels helpful. A majority of Americans also said they would choose lower-calorie food items if they had more information at their disposal—a possible sign that calorie counts could improve health.

But research also suggests that Americans are unlikely to change their behavior, even with the extra information about calories. “Four out of five controlled studies that compare restaurant patron choices in jurisdictions with and without menu labeling regulations before and shortly after menu labeling implementation have not found a relative reduction in calories purchased,” the researchers write.

Sarah Kliff flags more studies:

One study in Seattle, conducted between 2008 and 2010, didn’t find any change in the number of calories ordered at burger and sandwich restaurants — but did see a decline at taco and coffee stores.

Another study, conducted by two University of Minnesota researchers, found that when consumers were presented with calorie information in a survey setting, they would reduce their intended food order’s calories by about 3 percent. But when the same researchers tested out the calorie labels in a real-world fast food environment, nothing changed. Intentions, in other words, didn’t translate into behavior change.”Overall, our results show a considerable gap between actual choices and stated preferences with respect to fast food choices,” they write.

Matt Schiavenza examines related research:

Obviously, not everyone who eats at large chain restaurants is making a conscious effort to eat well. And even those who wish to make healthy choices sometimes lack an understanding of what, say, “1,000 calories” means. A study at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health found that restaurant customers in Baltimore made little attempt to eat healthily when shown calorie listings. But when food calories were matched with an equivalent amount of exercise, they made more of an attempt to eat less.