by Patrick Appel

As promised, Ross has responded to Andrew's defense of marriage equality. He mentions that a second post is in the works. I imagine Andrew will respond to both posts when he returns, but for now I'd like to focus on this bit:

[Conservatives in the 1970s] tended to interpret the spread of HIV as a case of an inherently self-destructive culture reaping what it had sowed. And that “inherently” assumption led them to ignore or downplay the conservative turn in gay culture that the disease inspired — a turn that led, eventually, to the arguments for gay marriage as the most stable and plausible alternative to the closet.

So what should conservatives have done instead? Basically, they should have pushed (in, let’s say, the early 1980s) for what Ryan Anderson and Sherif Girgis have urged as a contemporary compromise: A domestic partnership law designed to accommodate gay couples without being sexuality-specific. (In other words, it would be available to any couple who couldn’t legally marry each other: A pair of cohabitating siblings or cousins could enter into it as well, for instance.) This would have provided potential institutional support for gay monogamy, and a firm legal foundation for property sharing, visitation rights, and so on. It would have provided a legal standard for non-heterosexual households seeking to adopt a child. And no doubt various cultural forms and commitment rituals would have sprung up around it in the gay community. But at the same time, it would have maintained a real distinction between the general value of commitment and the specific and more societally-important value inherent in the traditional understanding of marriage.

Joe Carter has proposed a faux "civil union" along the same lines:

To me the civil unions should cover a broad range of domestic situations, such as two elderly sisters who share a home or a widowed parent of an adult child who has Down’s syndrome or other potentially disabling condition. Such legal protections should be completely desexualized and open to any two adults who desire to form a contractually dependent relationship.

Andrew's response at the time:

This is not support for civil unions. It is a simple codification of laws that enable any two people to make legal contracts. Every heterosexual already has access to both civil marriage and any or all of these other potential relationships. Homosexuals are uniquely discriminated against. Carter's proposal is actually designed to render gay relationships invisible and asexual. They are neither. It is designed to entrench the inferiority of the commitment of a gay person to his or her spouse in the law. It codifies inequality.

Beyond questions of inequality and asexuality, the introduction of a new social institution "available to any couple who couldn’t legally marry each other" strikes me as far more dangerous to heterosexual marriage than allowing gays into the institution. There are states and nations that allow civil unions, domestic partnerships, and same-sex marriages. I know of no nation or state that has adopted the sort of "domestic partnership" Ross promotes. The closest thing I can think of is France's civil union law, which has undermined marriage to a degree no marriage equality bill ever has.

The decline in the marriage rate worries Ross to no end, but his plan would only accelerate that trend. Marriage bundles financial and romantic interests together in one package. By unbundling, Ross makes marriage less attractive. Under Ross's proposal I'd be able to get a domestic partnership with my business partner, my neighbor, my housemate, my uncle, my cousin, my best friend – anyone who I can't marry already. By giving a non-romantic partner a financial stake in my life, and me in his, I've erased a primary motivation for marriage.

Ross says that this domestic partnership would allow for adoption. Following Ross's guidelines, let's pretend that I'm a heterosexual male in a domestic partnership with my heterosexual best friend. We decide that we want to adopt a child together, a right it appears we would have under Ross's law. What happens, several years later, when one of us meets a woman we want to marry? How do you resolve the domestic partners' financial obligations to each other and the custody battle? In what universe are the likely untended consequences from creating such a new social institution less worrying than allowing gays into an existing one?

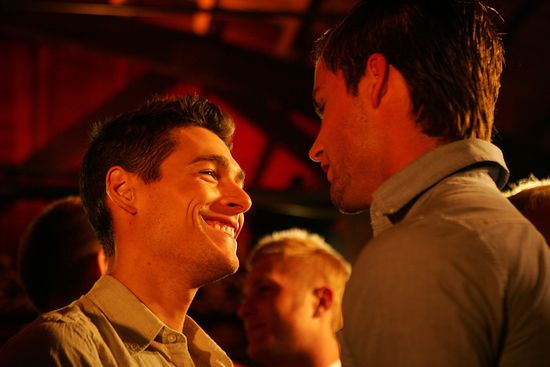

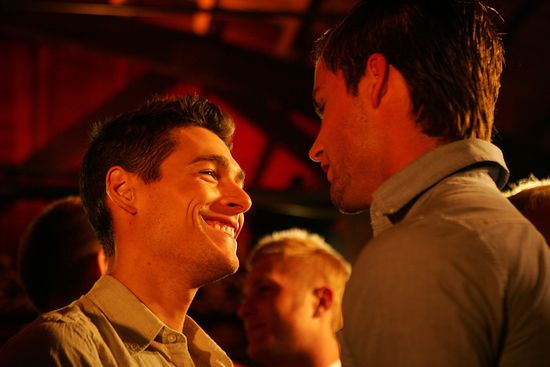

(Photo: David McNew/Getty.)