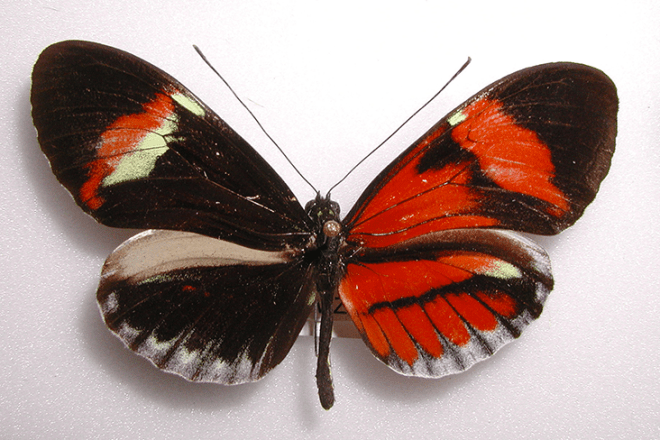

Ferris Jabr spoke with Nipam Patel, who studies gynandromorph butterflies, which have both male and female characteristics:

Every now and then he has encountered specimens such as the Heliconius butterfly [see above]. It’s a member of a colorful tribe in which males and females look nearly identical. Patel identified this butterfly as a gynandromorph because the two halves of its abdomen differed subtly in size and structure, one having male genitalia and the other female. Its wings should have been the same, but they weren’t.

Patel realized that, in addition to being doubly sexed, this particular insect might have a mixed identity. The patterns on its wings betrayed underlying genetics that could not be explained solely by a medley of female and male cells. … [T]he two wings had clearly activated different color pattern genes, indicating two entirely different genomes. When gynandromorphs differ in more than their sex characteristics, Patel thinks you could be looking at two animals in one.

How could that happen?

An insect egg cell harbors a smaller sister cell known as a polar body—a leftover from the cell division that created the egg cell. Sometimes two sperm manage to slip inside the egg and fertilize the egg’s nucleus as well as the polar body, creating two embryos that develop more or less like conjoined twins.

The two animals’ cells may not always keep to their own sides, however, which could explain why sometimes a gynandromorph has bilateral asymmetry and sometimes ends up a mosaic, with a splattering of opposite cells across a center line. Although other scientists have previously suggested that double fertilization accounts for some gynandromorphs, Patel has uncovered some of the clearest evidence to date.

Gynandromorphs’ duality calls to mind Plato’s Symposium, in which Aristophanes explains the origin of the sexes with a unique creation myth: In the beginning, he says, there were double-bodied primal humans—man and man, woman and woman, and man and woman—until, angered by their hubris, Zeus split them with bolts of lightning. But such duality is not just the stuff of myth.

Hedwig’s rendition of that myth:

(Image of Heliconius butterfly courtesy of Nipam Patel)