Timothy B. Lee explains the net neutrality proposal, announced yesterday, that the FCC is asking for public comment on:

When Chairman [Tom] Wheeler leaked a first draft of his network neutrality proposal to the press, it didn’t get a positive reception from network neutrality supporters. Wheeler’s rule would have allowed internet service providers to create “fast lanes” on the internet, provided that doing so was “commercially reasonable.”

Net neutrality supporters have been pressuring the agency to take a more aggressive approach, called reclassification. That means the FCC would declare broadband internet service a common-carrier telecommunications service, which would give the agency broader powers to regulate it. That could create some legal and political headaches, but it would likely put network neutrality regulations on a firmer legal footing in the long run.

The [notice of proposed rulemaking] leaves both options open, and asks the public for advice about which approach is better.

David Dayen notes that Wheeler’s preferred course of action isn’t as strong a safeguard of net neutrality as he claims:

Just listening to Wheeler today, you’d have thought he was the biggest Internet freedom activist in the country. “If telecoms try to divide haves and have-nots, we’ll use every power to stop it,” he said at the meeting. “Privileging some network users in a manner that squeezes out smaller voices is unacceptable.” Unfortunately, according to Craig Aaron of Free Press, Wheeler’s “rhetoric doesn’t match the reality of what’s in the rules.” They believe that Wheeler’s plan, which he says would prevent blocking or slowing of websites and prohibit “commercially unreasonable” fast-lane deals on a case-by-case basis, is impractical and legally dubious. “The only way to achieve his goals would be to reclassify broadband under Title II,” said Aaron.

Judis also spots a loophole:

Internet providers can violate net neutrality by setting up their own fast lane and charging content providers who want to use it, or they can charge content providers who want to connect directly with the internet provider without going through intermediate networks. That’s called “peering.” Comcast now charges Netflix an extra fee for connecting directly to its network. In exchange, Netflix gets faster and more dependable streaming on its videos. Wheeler’s proposals conspicuously ignore peering. It is, he said, “a different matter that is better addressed separately.” …

As a sop to the Democrats on the commission, and to Free Press, the Consumers’ Union, and other proponents of net neutrality, Wheeler included in his proposals the question of whether reclassifying the internet would provide “the most effective means of keeping the internet open.” He didn’t propose the FCC reclassify the internet, only that it consider doing that as one among several options. And it’s not going to happen.

Larry Downes opposes classifying the Internet as a public utility:

Internet access speeds and the range of useful applications have both improved by orders of magnitude over the last decade and a half, precisely because there were no federal or state agencies micromanaging their evolution, resulting in over a trillion dollars in private infrastructure investment. During that time, to pick a close comparison, the closely regulated public utility telephone network has fallen into decay and disuse. It will soon be absorbed into better and cheaper Internet-based alternatives.

Those who think that we should turn management of the Internet’s infrastructure over to the government had better dig out their 2400 baud modems. Not long ago, that was the “Internet as we know it.” Thank goodness it was allowed to evolve.

Suderman is on the same page:

Back in 1998, under President Bill Clinton, the agency submitted a report to Congress concluding that, for multiple reasons, Internet access was “appropriately classed” as an information service under Title I. One of the points the report made was that the Internet is more than just a dumb-pipe for carrying information. Yes, it involves data transport, “but the provision of Internet access service crucially involves information-processing elements as well; it offers end users information-service capabilities inextricably intertwined with data transport.” In other words, it simply doesn’t make sense to classify Internet access as a utility because the service involves than mindlessly moving packets of information from one place to another. And reclassification, the report warns, would result in “negative policy consequences”—specifically, it could have “significant consequences for the global development of the Internet.”

Over the last 16 years, that approach has given us the rapidly growing, innovative Internet we have today.

But Marvin Ammori argues that the FCC’s oversight facilitated innovation:

The past decade of tech innovation may not have been possible in an environment where the carriers could discriminate technically and could set and charge exorbitant and discriminatory prices for running internet applications. Without the FCC, established tech players could have paid for preferences, sharing their revenues with carriers in order to receive better service (or exclusive deals) and to crush new competitors and disruptive innovators. Venture investors would have moved their money elsewhere, away from tech startups who would be unable to compete with incumbents. Would-be entrepreneurs would have taken jobs at established companies or started companies in other nations. The FCC played an important role. The Chairman and this FCC shouldn’t break that.

Timothy B. Lee also addresses some of the arguments against reclassification, including that it would stifle investment:

Network neutrality supporters say this concern is overblown because of forbearance. That’s a legal procedure that allows the FCC to choose not to enforce provisions of the law that are deemed overly burdensome or counterproductive. But [legal scholar Gus] Hurwitz argues that the FCC has never tried to use forbearance on the scale that would be required to apply telecommunications regulations to the modern internet. It could become a legal quagmire and at a minimum it could become a distraction for FCC decision makers.

Reclassification opponents say broadband providers will be less willing to open their wallets when there’s a lot of uncertainty about when and how they’ll be allowed to profit from their networks. Of course, as Vox’s Matt Yglesias has noted, the [National Cable & Telecommunications Association’s] own statistics suggest that cable companies are investing less in their networks today than they did in the early 2000s, a time when there was a lot of uncertainty about the legal status of broadband networks.

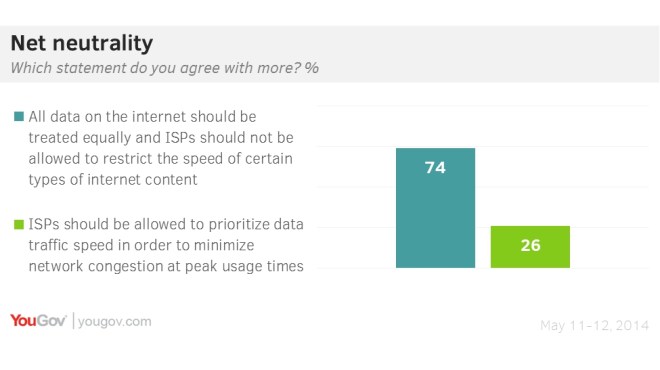

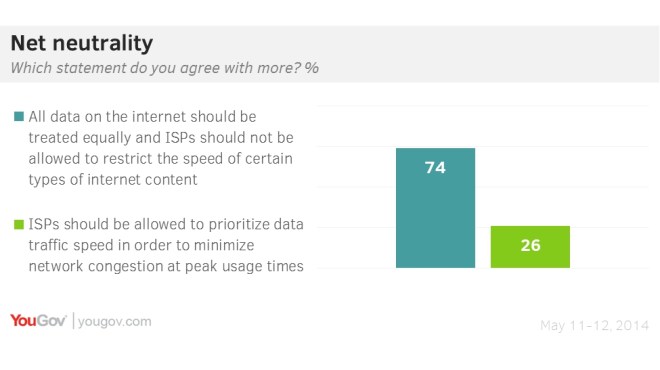

Meanwhile, net neutrality remains popular with the public, as the chart seen above illustrates. Steven A. Vaughan-Nichols points out that major Internet companies also support it:

You might think that today’s dominant Internet companies would favor this move [to allow “fast lanes”] as well. After all, while they’d end up paying more, this move would make sure they wouldn’t have competition in the future. Guess what? The top cloud company, Amazon; the top Web company, Google; and the top Internet video company, Netflix, all oppose this change. They, under the umbrella of the Ammori Group, a Washington DC-based public policy law-firm, all want the old-style net neutrality where companies can compete fairly with each other.

Heck, even the Internet providers, such as Level 3, which provides Internet service to the last mile ISPs want good, old net neutrality and not this new abomination. When the only ones supporting the FCC’s new position are the handful of companies that will directly benefit from it, is that really a fair position? I don’t think so.