by Chris Bodenner

A reader writes:

I recommend Pedro the Lion. It's pretty heavy and often crushingly-depressing music from a deeply disturbed mind, but nonetheless deeply religious. As for songs, I'd recommend "Diamond Ring" above all others, but also "Bad Things to Such Good People" and "Lullaby".

Another writes:

David Bazan, formerly of Pedro the Lion, has true indie bonafides with releases on Jade Tree and a history in the Seattle hardcore scene. Not all his music is related to religion, but damn near every interview feels the need to address the seeming paradox of his beliefs and his musical tastes. He's taken a lot of flack for what one Pitchfork-type review lamented as "his unfortunate hard-on for Jesus."

Another:

I can't really say if this is contemporary since he has since become an atheist, but Bazan is a pretty iconic figure as far as indie Christian music goes. The fact that he still has been invited to perform at Christian music festivals is also pretty intriguing at that. His music, while pretty ridiculously honest, personal, somber and occasionally satiric probably isn't something you'd want played at a religious service however, either by mood or content. The way he writes about sex, modernism, and criticizing church itself. And uses obscenities. Of course, probably the most interesting thing about him is listening over the course of his music how he lost his Faith in God.

Another:

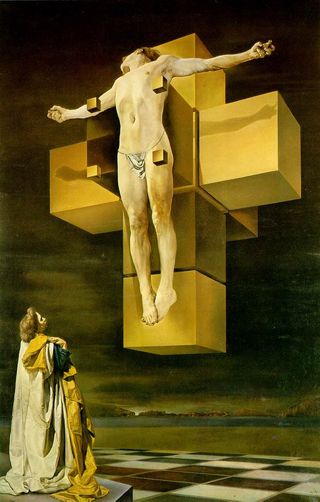

I remember hearing Pedro the Lion in youth group growing up in the '90s, and I was struck by his frank and honest depiction of faith. Perhaps he was too honest: Bazan has since given up his faith, and that has been hard for some in his Christian audience to understand. Check out a song from his recent "break up with God" album [seen above].

Another:

His latest album, "Curse Your Branches," is a nakedly emotional document of his wrestling with and eventual abandonment of belief mixed up with confessions of alcoholism, problems in his marriage, and the struggle to be a good father. Though the album is about Bazan's abandonment of faith, it is ironically the most Christian album I've heard in years because of the way Bazan honestly wrestles with issues of faith and identity. Plus, the songs are terrific. Lots of terrific melodies, memorable hooks, and production touches that pull in from dozens of influences, but still sound cohesive and unique.

Another:

He began doing concept story-albums with themes of morality, relationships, and mortality. Now he's doing music under his own name and it's gotten to the point where it's agnostic, sometimes really angry-at-God stuff. But it seems like there's always an undercurrent of the faith he knows he can't forget.

Bazan talked about his faith on his DVD, "Alone At The Microphone":

If Jesus was little more than a uniquely-adept Jewish mystic with a profound experience of the Divine (God-as-“Daddy,” a pretty great idea), then while that is profound, it’s no reason for me to follow him uniquely as opposed to the path of the Buddha, the Hindu mystics, or the Kabbalah.

If Jesus was little more than a uniquely-adept Jewish mystic with a profound experience of the Divine (God-as-“Daddy,” a pretty great idea), then while that is profound, it’s no reason for me to follow him uniquely as opposed to the path of the Buddha, the Hindu mystics, or the Kabbalah.

It is worth pointing out that inasmuch as the doctrines of the 4th and 5th centuries sought to articulate Jesus’ “divinity” – that he was “God from God,” and so God’s very self-expression in our common history – those doctrines did as much to preserve the distinctiveness and integrity of his humanity, and so to place brakes upon any tendency, whether explicit or subtle, to blur the distinction of “God” and “creature.”

It is worth pointing out that inasmuch as the doctrines of the 4th and 5th centuries sought to articulate Jesus’ “divinity” – that he was “God from God,” and so God’s very self-expression in our common history – those doctrines did as much to preserve the distinctiveness and integrity of his humanity, and so to place brakes upon any tendency, whether explicit or subtle, to blur the distinction of “God” and “creature.”