Frida Ghitis thinks not. Seth Masket differs:

[W]hy dissuade voters from evaluating the candidates at a time like this? This is a moment when action by the federal government is (nearly) universally regarded as being necessary. Is it not appropriate to consider how the president is actually administering it? And what would be better to consider? Debate performance? Likability? "Vision"? I'd say that the economy would be important, and voters actually do consider that, but the president has a far greater direct impact on disaster relief than he does on economic growth.

The issue certainly helped sway Mayor Bloomberg's vote, who, like The Economist, is endorsing the president:

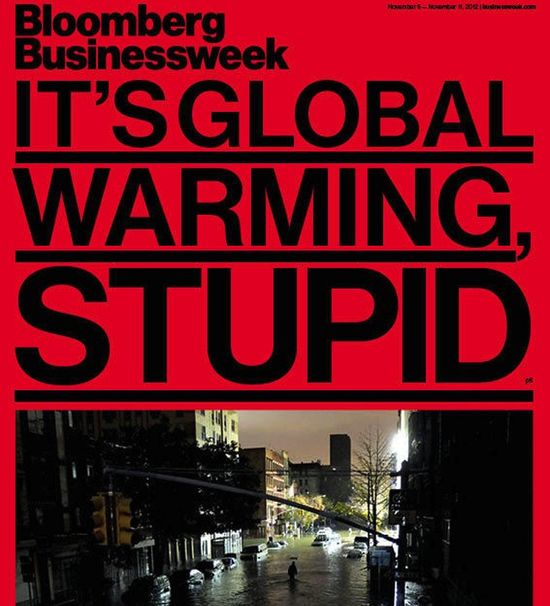

The devastation that Hurricane Sandy brought to New York City and much of the Northeast – in lost lives, lost homes and lost business – brought the stakes of Tuesday’s presidential election into sharp relief. The floods and fires that swept through our city left a path of destruction that will require years of recovery and rebuilding work. And in the short term, our subway system remains partially shut down, and many city residents and businesses still have no power. In just 14 months, two hurricanes have forced us to evacuate neighborhoods – something our city government had never done before. If this is a trend, it is simply not sustainable.

Our climate is changing. And while the increase in extreme weather we have experienced in New York City and around the world may or may not be the result of it, the risk that it might be – given this week’s devastation – should compel all elected leaders to take immediate action.

Here in New York, our comprehensive sustainability plan – PlaNYC – has helped allow us to cut our carbon footprint by 16 percent in just five years, which is the equivalent of eliminating the carbon footprint of a city twice the size of Seattle.  Through the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group – a partnership among many of the world’s largest cities – local governments are taking action where national governments are not.

Through the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group – a partnership among many of the world’s largest cities – local governments are taking action where national governments are not.

But we can’t do it alone. We need leadership from the White House – and over the past four years, President Barack Obama has taken major steps to reduce our carbon consumption, including setting higher fuel-efficiency standards for cars and trucks. His administration also has adopted tighter controls on mercury emissions, which will help to close the dirtiest coal power plants (an effort I have supported through my philanthropy), which are estimated to kill 13,000 Americans a year.

Mitt Romney, too, has a history of tackling climate change. As governor of Massachusetts, he signed on to a regional cap- and-trade plan designed to reduce carbon emissions 10 percent below 1990 levels. "The benefits (of that plan) will be long- lasting and enormous – benefits to our health, our economy, our quality of life, our very landscape. These are actions we can and must take now, if we are to have ‘no regrets’ when we transfer our temporary stewardship of this Earth to the next generation," he wrote at the time.

He couldn’t have been more right. But since then, he has reversed course, abandoning the very cap-and-trade program he once supported. This issue is too important. We need determined leadership at the national level to move the nation and the world forward.

I believe Mitt Romney is a good and decent man, and he would bring valuable business experience to the Oval Office. He understands that America was built on the promise of equal opportunity, not equal results. In the past he has also taken sensible positions on immigration, illegal guns, abortion rights and health care. But he has reversed course on all of them, and is even running against the health-care model he signed into law in Massachusetts.

If the 1994 or 2003 version of Mitt Romney were running for president, I may well have voted for him because, like so many other independents, I have found the past four years to be, in a word, disappointing.

In 2008, Obama ran as a pragmatic problem-solver and consensus-builder. But as president, he devoted little time and effort to developing and sustaining a coalition of centrists, which doomed hope for any real progress on illegal guns, immigration, tax reform, job creation and deficit reduction. And rather than uniting the country around a message of shared sacrifice, he engaged in partisan attacks and has embraced a divisive populist agenda focused more on redistributing income than creating it.

Nevertheless, the president has achieved some important victories on issues that will help define our future. His Race to the Top education program – much of which was opposed by the teachers’ unions, a traditional Democratic Party constituency – has helped drive badly needed reform across the country, giving local districts leverage to strengthen accountability in the classroom and expand charter schools. His health-care law – for all its flaws – will provide insurance coverage to people who need it most and save lives.

When I step into the voting booth, I think about the world I want to leave my two daughters, and the values that are required to guide us there. The two parties’ nominees for president offer different visions of where they want to lead America. One believes a woman’s right to choose should be protected for future generations; one does not. That difference, given the likelihood of Supreme Court vacancies, weighs heavily on my decision. One recognizes marriage equality as consistent with America’s march of freedom; one does not. I want our president to be on the right side of history. One sees climate change as an urgent problem that threatens our planet; one does not. I want our president to place scientific evidence and risk management above electoral politics.

Of course, neither candidate has specified what hard decisions he will make to get our economy back on track while also balancing the budget. But in the end, what matters most isn’t the shape of any particular proposal; it’s the work that must be done to bring members of Congress together to achieve bipartisan solutions. Presidents Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan both found success while their parties were out of power in Congress – and President Obama can, too. If he listens to people on both sides of the aisle, and builds the trust of moderates, he can fulfill the hope he inspired four years ago and lead our country toward a better future for my children and yours.

And that’s why I will be voting for him.

(Photo: US President Barack Obama comforts Hurricane Sandy victim Dana Vanzant as he visits a neighborhood in Brigantine, New Jersey, on October 31, 2012. By Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

Through the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group – a partnership among many of the world’s largest cities – local governments are taking action where national governments are not.

Through the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group – a partnership among many of the world’s largest cities – local governments are taking action where national governments are not.