by Jonah Shepp

As a child and teenager, I attended one of those New York City magnet schools that you read about from time to time, such as when an alum tentatively proposes to shut them all down. Accordingly, I share an alma mater with some notable individuals. The year I graduated, our commencement ceremony attracted a moderate crowd of local paparazzi on account of our guest speaker: Cynthia Nixon, class of ’84. In terms of pure star power, we had outdone the class of 2002, whose distinguished alumnus had been Elena Kagan, at the time merely the first female dean of Harvard Law School. Yeah, that kind of high school.

But celebrity aside, Nixon’s address to our class was actually more insightful than I, at 17, had expected. After the customary platitudes about lifelong friendships and school pride, she got to the point, which she summed up in four words: “Get out of here.”

Now what she meant by this was that if we lived our entire lives in New York, we’d limit the expansion of our minds much more than we realized. Growing up in an international megacity, it’s easy for native New Yorkers to fool ourselves into thinking that we are citizens of the world simply because the world has moved in down the block. The thrust of Nixon’s address to us was that this was a fallacy, and that if we really wanted to get some perspective on how unusual our metropolitan upbringings had been, we ought to spend some time not just traveling but living outside the city, and if we had the chance, outside the country as well.

Four years later, after finishing college in the opening act of the Great Recession with no prospects or plans for the future, I took advantage of a random opportunity and got out of here. Specifically, I moved to Jordan, where I lived for the better part of the next several years. For those who say you can’t learn anything from Hollywood, let me tell you something: Cynthia Nixon was right.

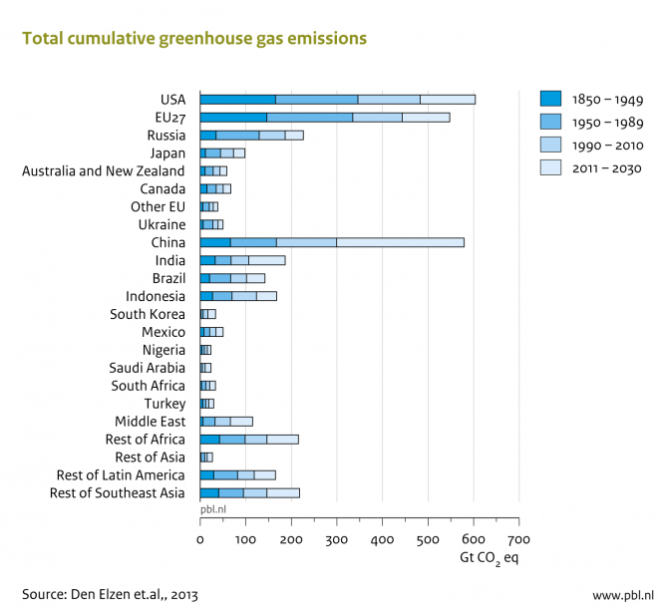

Living abroad, especially in a milieu so different from that of my childhood, did for me what no amount of formal education could: it challenged me to look at myself, America, and the world, from the standpoint of a foreign Other; and revealed the limits of my ability to inhabit that standpoint. It complicated my narrative of history and showed me how incredibly privileged I was to be an American citizen, starting with the fact that most people can’t just up and decide to move to another country for a while.

Probably the most significant impression Jordan made on me was how it guided the evolution of my views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Jordan bore the brunt of both the 1948 and 1967 Palestinian refugee crises and at least 50-60% of its population is of Palestinian origin (or rather, was; the Syrian crisis has increased Jordan’s population by 10 percent). In any case, a majority of the friends I made in Jordan are of Palestinian descent, and it’s harder to deny people’s rights or historical narratives when you actually know them. I’ve written at length elsewhere about what it was like to live there as an American Jew, and I’ll likely touch on this again in a separate post this week, but the moral of the story is that people’s world views are always and everywhere shaped by experience, and it is always worth considering how someone arrived at an opinion before holding them in judgment over it, even if I don’t share it, and even if I believe it to be objectively incorrect. This is a skill I find lacking in the most polemical of the opining class, and not only in discussions of Israel and Palestine.

I also got a good firsthand look at how incredibly lucky I am to be an American. A US or EU passport remains an object of envy around the world, even among people who care little for American or European culture or values. There’s an awful lot to be said here, most of it obvious, but it bears remembering that the accident of my birth on American soil holds open doors for me that remain shut to the majority of the world. My experience of expatriate life was completely different than those of the vast majority of emigrants, who leave their countries because they have to, not because they want to. And needless to say, living in a country that does not quite have a free press, free speech, or free religion made me all the more appreciative of what America does right. These are privileges worth checking from time to time.

More broadly, I think the experience of living abroad showed me the extent to which the culturally progressive, “when you’re cut, you bleed” attitude toward people of various races and religions—the notion that we are all fundamentally the same—is true, as well as its limits. We are not all the same. Culture matters; it is as much a product of history as anything else that matters. But the human condition is a general state of affairs. A major feature of that condition today is the city, with its attendant poverty, crowding, crime, pollution, and traffic. These problems take a variety of shapes: Amman’s unemployment problem is very different in its origins and expressions than that of Caracas or Harare or Los Angeles, but the problem is fundamentally the same, and endemic to large cities. And global events like the Great Recession really are felt everywhere, in similar ways.

My point is that those who are fortunate enough not to live in failed states or active warzones (and let’s not forget about the millions who are), are worrying from day to day about the same things: rent, bills, food, family disagreements, lovers’ quarrels. When we pay attention to world events, we think of them first and foremost in terms of how they affect us directly. This narrow perspective is a natural result of the parochial concerns that rule our day-to-day lives, but a little appreciation for how universal those concerns are (that is to say, empathy) can go a long way toward broadening the individual perspective, softening prejudices, and healing enmities, which is the only way to permanently end wars.

I arrived at all these insights, such as they are, in the same way: simply by standing in another person’s shoes. That’s why I think my time as an expatriate strengthened my conviction, which I call humanism, that empathy is a sufficient cause for ethical action.

So now I put the question to you, dear Dishheads. I know by the views from your windows that we have readers from Denver to Dushanbe, and I know you didn’t all start out where you ended up, so to those of you who live or have lived outside the country of your birth: what motivated you to do so and how did the experience change you? Perhaps you haven’t lived abroad but have moved from, say, rural Kentucky to San Francisco, or vice-versa: a bigger change of scenery than crossing some international borders. I’d ask you the same question. Migration has always had a significant hand in history; in a global economy, that role is even greater. What has it meant to you? Email me your thoughts at dish@andrewsullivan.com.

(Photo: The view from my window—OK, balcony—in Amman, Jordan, by my roommate Matt, who was slightly better about taking pictures than I was.)