Salon's Justin Elliott says he has definitively resolved all conceivable doubts about Sarah Palin's biological maternity of Trig. I have to say my first instinct is to thank and congratulate him for doing what should have been done a long, long time ago. Before I go into the details, let me first, however, address the following canard:

Sullivan's refrain on this issue is that he does not endorse any conspiracy theory, he is merely asking questions. He simply wants Palin "to debunk this for once and for all, with simple, readily available medical records." He has proposed, for example, the release of "amniocentesis results with Sarah Palin's name on them."

It's worth noting that this posture is identical to the rhetoric used by Obama birthers (for instance, WorldNetDaily Birther czar Joseph Farah employs the "just asking for definitive piece of proof x" line here).

This is absurd. Obama has produced the most relevant, clear, unimpeachable, if humiliating, piece of empirical evidence that he is indeed a native-born US citizen. In fact, he produced it a long time ago. (I think he was right to do so, and the press was easily within bounds to ask. That's how these things should work.)

And there is a huge difference between someone asking for exactly that kind of proof, however distasteful, and someone continuing to ask for it after that proof has already been produced.

To equate my simple request for proof – a request first made in September 2008 – with a request for evidence even after it has been produced is not "worth noting." It's a smear.

And I have not shifted this position since the very beginning. In my view, a journalist doesn't have to engage in any consipracy theories in order to ask a public figure to verify a story that they tell as a core plank of their political candidacy – especially when verifying it should be easy. When the figure has publicly said she has already released the birth certificate – and she hasn't – and when she demands further digging into the Obama birth certificate after it has been produced, and when she once demanded that her opponent for the mayoralty of Wasilla provide his actual marriage license to prove his wife was his wife (and he did), I see no reason whatever to apologize or regret asking her to put her medical records where her mouth is. She still hasn't.

Did Elliott ask Palin to do so himself? If you want an end to this, that is what you would do. It appears he hasn't. He has asked fellow journalists what they saw and believed. I'm not sure why a reporter decides to ask fellow reporters for eye-witness accounts when he could simply ask Palin for proof. Well, I do see why – which I'll tackle in a forthcoming post.

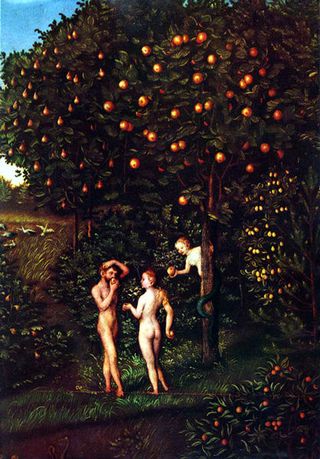

(Photo: Sarah Palin on March 26, 2008, three weeks before giving birth to a six-pound baby).

majority of Americans don't qualify either. Obviously, I don't consider this a negative. Obama is also bi-racial, instantly putting him in a relatively (if decreasingly) rare cultural position. And I think it's overly defensive to insist that Obama is in no way different than most Americans. He is. His formative years were spent shuttling between Indonesia and Hawaii, missing his Kenyan father. You cannot read "Dreams From My Father" without intuiting a very distinctive man in the history of the American presidency. I think it's a big advantage especially in foreign policy. And I think it's a transformative moment in the evolution of America – a multicultural, multiracial experiment in democracy that has a president that reflects its future.

majority of Americans don't qualify either. Obviously, I don't consider this a negative. Obama is also bi-racial, instantly putting him in a relatively (if decreasingly) rare cultural position. And I think it's overly defensive to insist that Obama is in no way different than most Americans. He is. His formative years were spent shuttling between Indonesia and Hawaii, missing his Kenyan father. You cannot read "Dreams From My Father" without intuiting a very distinctive man in the history of the American presidency. I think it's a big advantage especially in foreign policy. And I think it's a transformative moment in the evolution of America – a multicultural, multiracial experiment in democracy that has a president that reflects its future.

decades; we are able to give wounded soldiers new limbs and tell cancer patients that hope is real and not be lying. We can map the human genome and devise revolutionary new treatments for previously fatal conditions; and we can extend life beyond any previous human generation’s imagination. Remember all those old black and white movies where you saw scenes in which the father of a sick child simply says “we don’t have the money for the operation.” And little Johnny dies. How far away that passive stoicism now seems. Within a few decades, what was once taken as fate is now rejected as a moral obscenity. Because, given what we have achieved in those decades, it is a moral obscenity. We are all physical beings and we are never as equal as when we face sickness and mortality. Because we have so feasted on the tree of knowledge, it becomes morally intolerable to prevent its fruit from being given to all. At the same time, as a matter of economics and mathematics, we also know at the back of our minds that we simply cannot give it to all – because these breakthroughs involve huge investment, highly trained experts, and inherently expensive technology. And as the options for health grow, we are forced to make choices that were previously out of our grasp, and those choices make us, in some way, gods. We collectively decide who can live for how long and who can die – because for the first time in human history we really have that choice. In fact, we have no escape from that choice. Healthcare is no longer triage, where sickness and death is the norm; it is an open-ended, blurry range of positive choices, where wellness is the expectation. At some point, then, we have to ration. You see this in socialized systems as well as hybrid ones. In Britain, the National Health Service confronts medical opportunities unknown when it was set up sixty years ago. And so, as the years went by, you saw more waiting lists and more de facto rationing – or a spending splurge under Blair and Brown that was simply unsustainable, and ended in piles of debt. Nonetheless, Cameron is refusing to cut from the NHS – which makes the cuts elsewhere all the more draconian. Why? Because he is a decent chap who has seen family illness upfront, and cannot really deny his fellow human beings the ability to rescue their infant from early death or cure a loved mother or keep someone with HIV or Parkinson’s as healthy as possible. In the US, you see the same process – but where no single entity gets to dictate the outcome. The result? Each agent passes the buck to everyone else – from insurance companies to doctors and hospitals to patients and back to government and then back again. And so instead of rationing by government, we have soaring healthcare costs as the least worst option. We can try to find efficiencies to make these god-like choices less onerous, but it often feels like running down an up escalator. We’re lucky if we merely stay in the same place. In fact, we have long since been going backward – hence the alarming projections of healthcare spending essentially crowding out every other economic or government activity in a few years’ time. We can try to increase efficiencies – and the ACA has not been fully credited with the many good ideas and experiments buried inside it. Or we can do what Ryan proposes, which is essentially severing the whole idea of an entitlement to good health, and turn it into a simple lump sum for seniors, after which they have to pay for themselves or have less health or longevity. Ezra Klein is right to remind us of the distinction here.

decades; we are able to give wounded soldiers new limbs and tell cancer patients that hope is real and not be lying. We can map the human genome and devise revolutionary new treatments for previously fatal conditions; and we can extend life beyond any previous human generation’s imagination. Remember all those old black and white movies where you saw scenes in which the father of a sick child simply says “we don’t have the money for the operation.” And little Johnny dies. How far away that passive stoicism now seems. Within a few decades, what was once taken as fate is now rejected as a moral obscenity. Because, given what we have achieved in those decades, it is a moral obscenity. We are all physical beings and we are never as equal as when we face sickness and mortality. Because we have so feasted on the tree of knowledge, it becomes morally intolerable to prevent its fruit from being given to all. At the same time, as a matter of economics and mathematics, we also know at the back of our minds that we simply cannot give it to all – because these breakthroughs involve huge investment, highly trained experts, and inherently expensive technology. And as the options for health grow, we are forced to make choices that were previously out of our grasp, and those choices make us, in some way, gods. We collectively decide who can live for how long and who can die – because for the first time in human history we really have that choice. In fact, we have no escape from that choice. Healthcare is no longer triage, where sickness and death is the norm; it is an open-ended, blurry range of positive choices, where wellness is the expectation. At some point, then, we have to ration. You see this in socialized systems as well as hybrid ones. In Britain, the National Health Service confronts medical opportunities unknown when it was set up sixty years ago. And so, as the years went by, you saw more waiting lists and more de facto rationing – or a spending splurge under Blair and Brown that was simply unsustainable, and ended in piles of debt. Nonetheless, Cameron is refusing to cut from the NHS – which makes the cuts elsewhere all the more draconian. Why? Because he is a decent chap who has seen family illness upfront, and cannot really deny his fellow human beings the ability to rescue their infant from early death or cure a loved mother or keep someone with HIV or Parkinson’s as healthy as possible. In the US, you see the same process – but where no single entity gets to dictate the outcome. The result? Each agent passes the buck to everyone else – from insurance companies to doctors and hospitals to patients and back to government and then back again. And so instead of rationing by government, we have soaring healthcare costs as the least worst option. We can try to find efficiencies to make these god-like choices less onerous, but it often feels like running down an up escalator. We’re lucky if we merely stay in the same place. In fact, we have long since been going backward – hence the alarming projections of healthcare spending essentially crowding out every other economic or government activity in a few years’ time. We can try to increase efficiencies – and the ACA has not been fully credited with the many good ideas and experiments buried inside it. Or we can do what Ryan proposes, which is essentially severing the whole idea of an entitlement to good health, and turn it into a simple lump sum for seniors, after which they have to pay for themselves or have less health or longevity. Ezra Klein is right to remind us of the distinction here.