Francis wants to make it with a new encyclical:

Its message will be spread to congregations around the world by Catholic clergy, mobilising grassroots pressure for action ahead of the key UN climate summit in December in Paris. The encyclical may be published as early as March, and may be couched in terms of the biblical parable of the Good Samaritan, which teaches that we have responsibilities to our fellow humans.

It will be the first encyclical to address concerns about a global environmental issue, and will provide “important orientation” to all Catholics to support action on climate change, says Bishop Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo, chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and Social Sciences in Vatican City. Last May, he organised a workshop there discussing the science and impact of climate change. Participants issued a hard-hitting statement, which laid the groundwork and set the tone for the encyclical.

The most likely thrust of the pope’s appeal will be that failure to combat climate change will condemn the world’s poorest people to disproportionate harm. “The sad part is that the poorest three billion will be the worst affected by the impacts of climate change, such as sea level rise and drought, but have had least to do with causing it,” says Veerabhadran Ramanathan, a climatologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California, and a scientific adviser to the Vatican on the encyclical.

Thursday, when asked if he thought mankind was mostly to blame for global warming, the Pope responded:

“I don’t know if it is all (man’s fault) but the majority is, for the most part, it is man who continuously slaps down nature,” he said. The words were his clearest to date on climate change, which has sparked worldwide debate and even divided conservative and liberal Catholics, particularly in the United States. “We have, in a sense, lorded it over nature, over Sister Earth, over Mother Earth … I think man has gone too far.”

When the encyclical was originally previewed late last month, Catholic Climate Covenant’s Dan Misleh put the move in context:

“It is the first time ever an encyclical letter has been written just on the environment,” Misleh said. “The faithful, including bishops, and all of us who adhere to the Catholic faith, are supposed to read it and examine our own consciences.”

Mobilizing believers to embrace climate action could be a very big deal, given the sheer number of people who identify as Catholic in the US—around 75 million—he said. “If we had just a fraction of those acting on climate change, it would be bigger than the networks of some of the biggest environmental groups in the US,” he said. “That could help change the way we live our lives, and impact our views on public policy.”

Plumer has more:

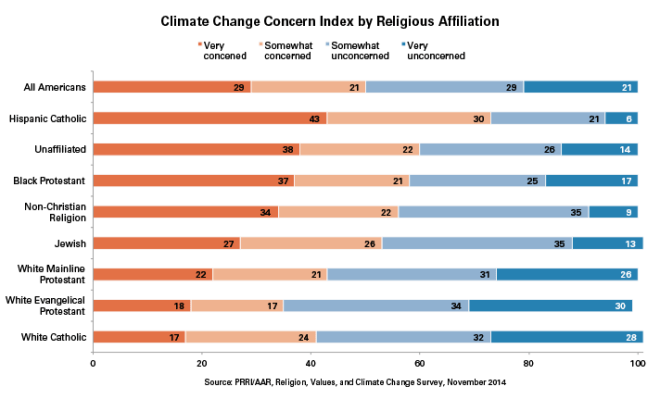

For what it’s worth, surveys in the US have found that white Catholics tend to be among the least concerned groups about climate change, whereas Hispanic Catholics are some of the most concerned. Here’s a PRRI poll from November 2014:

But, of course, Catholics don’t just automatically follow the pope’s lead on every last political question. (Gay marriage is a perfect example.)

And of course with the Pope’s high approval rating around the world, he might also be able to influence Evangelicals, who, as Chris Mooney noted last month, are already moving toward more environmental action:

The biblically based stewardship or “Creation Care” message — which went very, very mainstream [last] year in the blockbuster film Noah — may not have won out with a majority of these believers. But it appears to have made substantial inroads. And evangelicals leaders like the climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe are working every day to convince more believers, by making theologically (and politically) resonant arguments for why they need to take climate science seriously.

He’s cautiously optimistic:

There’s no doubt that many religious people around the world cling to their beliefs (or, to what they think their beliefs require) in the face of evidence, and history shows science-religion conflicts popping up at regular intervals. But it also shows something else: Believers who find a way to reconcile faith and science.

If Pope Francis continues on his current course, he has the power to make this latter group a whole lot more prominent than it already is.

But seeking more than just rhetoric, Leber challenges Francis to pony up the Vatican’s fossil fuel investments as well:

There are two main arguments for divestment from fossil fuels, on moral and financial grounds. The former is that we have responsibility not to aid companies that imperil the planet—God’s creation, according to Catholics—especially when it particularly impacts the poor. And while some financial experts claim divestment is impossible to detangle fossil fuels from a portfolio and retain balanced, stable growth, others argue that in a low-carbon world, fossil fuel stocks become worthless, risking ruin for those who retain too much faith in oil, gas, and coal. The head of England’s central bank, for instance, has already warned investors that their focus on short-term profits in the fossil fuel market may be foolish in the long-term. (Rolling Stone’s Tim Dickinson has a worthwhile read on the economics of divestment.)

One can see how the Vatican, which has an estimated $8 billion portfolio, could make waves—symbolically and financially—if it were to divest from fossil fuels. Environmental group 350.org is pushing the Church to do exactly that, and claimed Wednesday that hundreds of protesters attended a divestment vigil just before Francis arrived in Manila. Now it’s time for the Pope to put his words into action. What better way to show the world that 2015 is the year for global climate action than to lead by example?

Regardless, the editors of New Scientist are nonetheless pleased to have the Vatican as an ally:

For all the railing of secularists against the idea that the church has any special claim over morality, and despite its influence being [on the wane], many people heed religious authority more readily than any scientific or economic argument. And the pope’s case is one that leaders of rich, carbon-intensive nations are reluctant to put forward: that they owe it to the world’s poor to cut emissions.

Not every churchgoer will be swayed. Evangelicals are among the staunchest of climate sceptics; even those who accept the reality often view it as God’s will. It remains to be seen if the pope can appeal to these recalcitrants – or if the jeering of denialists will take on a theological, rather than scientific, tone (to which we can only say: god help us).

It was 350 years before a pope admitted that the church had wronged Galileo, whose reputed parting shot was to say of the Earth: “eppur si muove”– “and yet it moves”. In contrast, it has taken the Vatican hardly any time to accept that Earth is warming. It helps that the Bible contains precious few verses pertinent to carbon emissions. Perhaps we will start to see evidence reshaping the Vatican’s views on other issues where scripture still holds sway: the role of contraception in tackling population growth, say. One can only pray it will.