[Re-posted from earlier today]

Whenever I read the blog-posts of Walter Russell Mead, or the fulminations of Leon Wieseltier, or the sputtering harrumphs of John McCain, or the neoconservative or liberal internationalist horrified respect for Vladimir Putin’s Great Game of geo-politics, I find myself on the other side of a vast, intellectual chasm. I’ve tried at times in my head to engage the arguments, and have consistently found myself at a loss. It’s not the arguments for this or that military or diplomatic intervention that stump me. It’s the entire premise behind them.

At times, I’ve put it down to a very different response to the Iraq War. Many of these voices decrying Obama’s restraint in the face of evil or  distant conflict have not drawn the same lessons I did from that defining episode in American foreign policy in the 21st Century. I saw that war as an almost text-book refutation of the logic behind US intervention in this century. The Iraqis were not the equivalent of Poles in 1989. They were deeply conflicted about US intervention and Western liberalism and came to despise the occupying power. The US was not the exemplar of liberal democracy that it was in the Cold War. It was a belligerent state, initiating Israel-style pre-emptive wars, and using torture as its primary intelligence-gathering weapon. Its military did not defeat an enemy without firing a shot, as with the the end-game of the Soviet Union; it failed to defeat an enemy while unloading every piece of military “shock and awe” upon it. A paradigm was shattered for me – and shattered by plain reality. A realist is a neocon mugged by history.

distant conflict have not drawn the same lessons I did from that defining episode in American foreign policy in the 21st Century. I saw that war as an almost text-book refutation of the logic behind US intervention in this century. The Iraqis were not the equivalent of Poles in 1989. They were deeply conflicted about US intervention and Western liberalism and came to despise the occupying power. The US was not the exemplar of liberal democracy that it was in the Cold War. It was a belligerent state, initiating Israel-style pre-emptive wars, and using torture as its primary intelligence-gathering weapon. Its military did not defeat an enemy without firing a shot, as with the the end-game of the Soviet Union; it failed to defeat an enemy while unloading every piece of military “shock and awe” upon it. A paradigm was shattered for me – and shattered by plain reality. A realist is a neocon mugged by history.

But the more I ponder this, the more I wonder if it isn’t also rooted in an entirely different response to the end of the Cold War as well. I remember vividly some early disputes at TNR as the Soviet Union collapsed. Marty, in particular, was just as vigilant toward the new Russian government as he had been toward the Communist one (and that was during the elysian years of Yeltsin’s doomed, democratic experiment). I found this utterly baffling. For me, the fight against Communism was not a fight against Russia. They were separate entities; one was a global, expansionist ideology, capable of intervening across the planet; the other was a ruined but still proud regional power. Indeed, if we were to prevent a return to Communist norms, I believed we should expect Russia to flex some muscles in its area of influence, for the  Orthodox church to return as some sort of cultural unifier, for Russia to return to, well, being Russia, with some measure of self-respect. Magnanimity in victory was a Churchillian lesson I took to heart. I hoped – and hope – for more, but came to understand much more vividly what I had unforgivably forgotten after 9/11 – the perils of trying to force democratic advance in alien cultures and polities.

Orthodox church to return as some sort of cultural unifier, for Russia to return to, well, being Russia, with some measure of self-respect. Magnanimity in victory was a Churchillian lesson I took to heart. I hoped – and hope – for more, but came to understand much more vividly what I had unforgivably forgotten after 9/11 – the perils of trying to force democratic advance in alien cultures and polities.

For me, the end of the Cold War was a blessed permission to return to “normal”. And “normal” meant a defense of national interests and no countervailing ideological crusade of the kind the Communist world demanded. In time, it seems to me that the basic and intuitive foreign policy for the US would return to what it had been before the global ideological warfare against totalitarianism from the 1940s to the 1980s. The US would become again an engaged ally, a protector of global peace, but would return to the blessed state of existing between two vast oceans and two friendly neighbors. The idea of global hegemony – so alien to the vision of the Founders – would not appeal for long, at least outside the Jacksonian South. As Islamist terror traumatized us on 9/11, however, I reverted almost reflexively to the Cold War mindset – as did large numbers of Americans. It was the rubric we understood; and defining Islamism as the new totalitarianism helped dispel what then appeared as the delusions of the 1990s, when peace and prosperity seemed to indicate an “end of history”, in Frank Fukuyama’s grossly misunderstood and still brilliantly incisive essay.

From the perspective of 2014, however, the delusions seem to have been far more profound in the first decade of the 21st Century than in the last decade of the 20th. The conflation of Islamism with Communism was far too glib – not least because the former was clearly a reactionary response to modernity, while the latter claimed to be modernity’s logical future; and the latter commanded a vast military machine, while the former had a bunch of religious nutcases with boxcutters. And the attempt to use neo-colonial military force to fight Islamism was clearly doomed to produce yet more Islamists – as the Iraq and Afghanistan interventions proved definitively. More to the point, Americans now understand this in ways that many in the elite don’t:

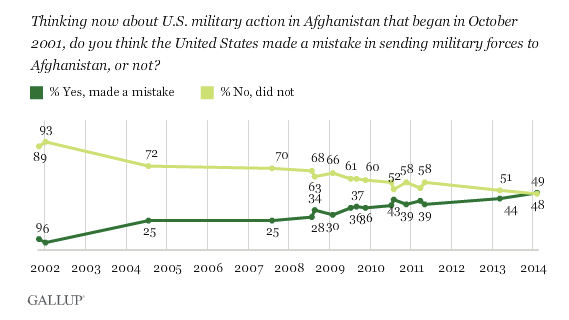

From 93 percent to 48 percent is quite some shift in 12 years. Sometimes, when I’m criticized for changing my mind on the wars against Islamist terror, as if I were some kind of incoherent madman, I can’t help chuckling. I can see why it might seem fickle or unprincipled or irrational if I were alone. But when there’s a stampede among Americans on exactly the same lines, I’m clearly not an outlier. People changed their minds because the facts forced them to. The polling on the Iraq war is even worse:

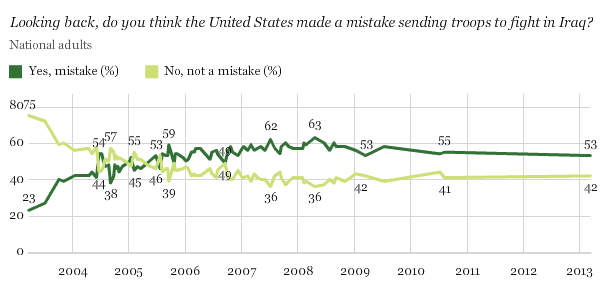

Again, the shifts are dramatic: from 23 percent believing the war was a mistake at the start to 53 percent ten years later. A third of Americans reversed themselves.

Now, you could argue that these results are just a function of obvious failures in war-planning, or war-fatigue, or the recession. But I think that condescends too much to American public opinion. In thinking about intervention, America no longer has some global ideological rival to counter, and in so far as America does (i.e. Islamist terrorism), there is a widespread understanding that our military attempts to stymie it have been costly failures at best and cripplingly counter-productive at worst. This is a real shift, and I can only recommend Ross Douthat’s latest blog-post that explicates it further.

What Ross is arguing is that Sam Huntington was right to see the persistence of conflict and warfare where the civilizations meet and clash:

Crises keep irrupting along the rough borders that Huntington sketched — where what he called the “Orthodox” world overlaps with the West (the Balkans, the Ukraine), along Islam’s so-called “bloody borders” (from central Africa to Central Asia), in Latin American resistance (in Venezuela’s Chavismo, Bolivia’s ethno-socialism, and the like) to North American-style neoliberalism, and to a lesser extent in the long-simmering Sino-Japanese tensions in North Asia.

But these conflicts mean less to us, because so much less is at stake than it once was. And the reason for that is that Fukuyama was also right:

Huntington’s partial vindication hasn’t actually disproven Fukuyama’s point, because all of these conflicts are still taking place in the shadow of a kind of liberal hegemony, and none them have the kind of global relevance or ideological import that the conflicts of the 19th and 20th century did. Radical Islam is essentially an anti-modern protest, not a real alternative … China’s meritocratic-authoritarian model has a long way to go to prove itself as anything except a repressive Sino-specific kludge … Chavismo and similar experiments struggle to maintain even domestic legitimacy … and what Huntington called the Western model is still the only real aspiring world-civilization, with enemies aplenty, yes, but also influence and admirers in every corner of the globe.

Ross’ is a really elegant overview of the real, historical context for the deployment of American military and even diplomatic and economic power in this century. Military power can achieve less and, more importantly, its success or failure in any specific context matters less. Obama’s restraint is not weakness; and trying to match Putin’s militarist bluster is a mug’s game. The most important thing the president says about Iran is not the need to prevent its developing an operational nuclear weapon, but the articulation of the truth that, compared with America’s global enemies in the past, Iran is a puny power, a failing economy, and a bankrupt ideology. Yes it can still do damage, and we should do our best to restrain it as best we can. But a full-scale war to disarm it? The costs would so vastly exceed the tiny benefits that you really have to be stuck in 1984 to contemplate it. We had the first iteration of this debate in 2008 – between the 20th Century nostalgic, John McCain, and the 21st Century realist, Barack Obama. And Obama won. And won again.

That verdict has not yet changed. And for good reason. What lies ahead is simply the task of resisting some primal impulse to return to the Cold War mindset. Which is what, I’d argue, Chuck Hagel’s plans for slimming the military are really all about.

(Photos: Getty Images)