The Islamic State has taken over the town of Sinjar in the country’s northwest, near the Syrian border. Sinjar is the homeland of the Yazidis, a religious minority that Joshua Landis warns is now in grave danger of persecution:

One of the few remaining non-Abrahamic religions of the Middle-East, the Yazidis are a particularly vulnerable group lacking advocacy in the region. Not belonging to the small set of religions carrying the Islamic label “People of the Book,” Yazidis are branded mushrikiin (polytheists) by Salafis/jihadists and became targets of high levels of terrorist attacks and mass killing orchestrated by al-Qaida-affiliated jihadists, following the instability brought about by the War in Iraq.

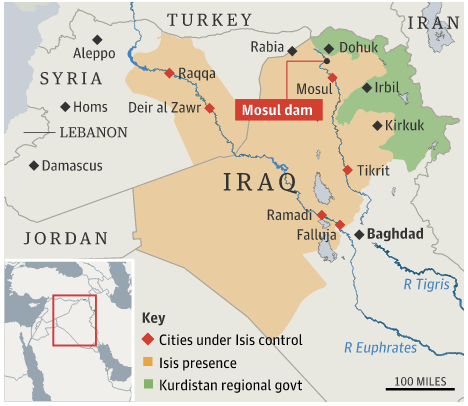

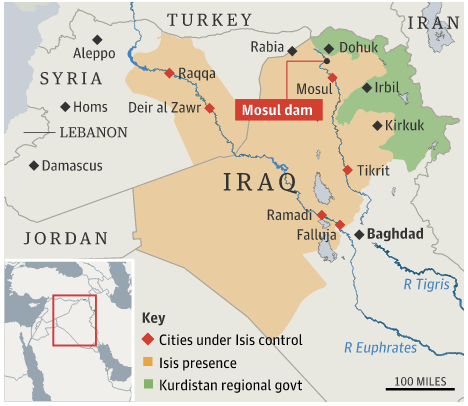

Today’s IS assault is already bringing about devastating consequences for Yazidis, who make up about 340,000 of Sinjar’s 400,000 inhabitants (this is a high estimate). Many have fled on foot through the desert, without food or water. Others fleeing in cars for Dohuk have been unable to make a clean escape, due to the inability of the roads to accommodate such a large flux of people. Thousands of cars are currently stranded west of the Tigris River.

Andrew Slater also fears for Sinjar’s religious minorities:

By the afternoon of Sunday, August 4, with ISIS in full control of Sinjar, terrified families from the area began their dangerous exodus. The speed with which ISIS engulfed the entire mountain range attests to the large numbers of fighters they brought to bear for this major offensive. Villagers in the Sinjar area gave accounts of girls and young women from their families being abducted by ISIS fighters and carried away. Countless families fled to the mountains above their villages where they are currently surrounded by ISIS controlled areas and are desperately calling friends and family members who escaped, pleading for help. Pictures of families hiding in the mountains have circulated widely on Iraqi social media.

Besides the Sayyida Zainab mosque, ISIS forces were reported to have blown up the Sharif Al-Deen shrine on the Sinjar mountainside, a holy place for Yezidis. The ISIS flag was also raised over the only remaining church in the Sinjar area. Within 24 hours, Sinjar has been transformed from a bustling community into a string of ghost towns.

In its rampage through northern Iraq, ISIS may also have captured Iraq’s largest dam:

Capture of the electricity-generating Mosul Dam, which was reported by Iraqi state television, could give the forces of the Islamic State (Isis) the ability to flood Iraqi cities or withhold water from farms, raising the stakes in their bid to topple prime minister Nuri al-Maliki’s Shia-led government. “The terrorist gangs of the Islamic State have taken control of Mosul dam after the withdrawal of Kurdish forces without a fight,” said Iraqi state television of the claimed 24 hour offensive. Kurdish officials conceded losses to Isis but denied the dam had been surrendered. A Kurdish official in Washington told Reuters the dam was still under the control of Kurdish “peshmerga” troops, although he said towns around the dam had fallen to Isis.

Meanwhile, jihadists affiliated with ISIS and the Syrian jihadist rebel group Jabhat al-Nusra have taken over the Lebanese border town of Arsal, but Zack Beauchamp assures us that this isn’t as scary as it seems:

ISIS’s actions in Arsal aren’t part of a deliberate expansion of the caliphate into Lebanon. Rather, Lebanese forces picked a fight with ISIS fighters who’d been pushed out of Syria. In purely geographic terms, this interpretation of the fighting makes more sense. … Lebanon, down near Damascus in the west, is really far from ISIS’ bases in north-central Iraq and northern Syria. It would be very, very hard for ISIS control territory far away in Lebanon in the same way it controls the caliphate proper.

That said, ISIS’ presence in Lebanon really could be destabilizing all the same. The Arsal fighting alone has already displaced 3,000 people and killed at least 11 Lebanese soldiers. And while ISIS is not trying to seize territory in Lebanon outright (not yet, anyway), the group is ramping up terrorist attacks there. “They’ve been bombing things, trying to get cells in Tripoli [and] Damascus,” Smyth says. “They’ve tried to use these different cells to bomb Iranian and Hezbollah targets there.”

In any case, Keating remarks that these developments are changing the calculus regarding ISIS’s staying power:

A few weeks ago, it seemed unlikely that ISIS could hold out for that long given the sheer number of regional actors it had picked fights with. But it seems like it’s not only holding out, it’s expanding its activities into new areas and taking on new rivals. It’s hard to imagine how it will be contained unless the various forces fighting it can somehow find a way to coordinate. For now, the center of the conflict seems to be the Mosul Dam. Will the prospect of power cuts or catastrophic flooding be enough to get Maliki’s government to work with his Kurdish rivals?

Siddhartha Mahanta notices that ISIS’s recent gains have prompted the Baghdad government to start cooperating with the Kurds:

That massive setback — which the peshmerga claim is a strategic retreat — reportedly led Maliki to back up the peshmerga with air support, as Reuters reported on Monday. “We will attack them until they are completely destroyed; we will never show any mercy,” a Kurdish colonel told the news agency. “We have given them enough chances and we will even take Mosul back. I believe within the next 48-72 hours it will be over.” So while Maliki is making good on his threat to use legal power to seize Kurd-claimed oil, he’s also sending in the planes to back the Kurds just as the myth of their apparent invincibility takes a potentially serious hit. It’s either a shrewd political move or a truly desperate cry for help. Baghdad and Erbil. These days, theirs is a tale of two frenemies.

And Dexter Filkins argues that we should be helping the peshmerga, too:

The militants in ISIS have swept across much of northern and western Iraq, and there is no sign that they have any intention of slowing down. In a surprising—and encouraging—turn, Maliki has apparently ordered the Iraqi Air Force to carry out air strikes to help the Kurds. That said, the Iraqi Army has proved itself utterly ineffectual in combating ISIS. If the U.S. decided to help the Kurds, there would be no guarantee that the Kurds wouldn’t later use those weapons to further their own interests. But what other choice is there? If anyone is likely to slow down ISIS, it’s going to be the Kurds—regardless of whatever they’re planning to do later on.