This time-lapse video purports to show the Israeli military flattening a Gaza neighborhood over the course of an hour. In Rashid Khalidi’s take, Israeli leaders have done the same to the peace process:

What Israel is doing in Gaza now is collective punishment. It is punishment for Gaza’s refusal to be a docile ghetto. It is punishment for the gall of Palestinians in unifying, and of Hamas and other factions in responding to Israel’s siege and its provocations with resistance, armed or otherwise, after Israel repeatedly reacted to unarmed protest with crushing force. Despite years of ceasefires and truces, the siege of Gaza has never been lifted.

As Netanyahu’s own words show, however, Israel will accept nothing short of the acquiescence of Palestinians to their own subordination. It will accept only a Palestinian “state” that is stripped of all the attributes of a real state: control over security, borders, airspace, maritime limits, contiguity, and, therefore, sovereignty. The twenty-three-year charade of the “peace process” has shown that this is all Israel is offering, with the full approval of Washington. Whenever the Palestinians have resisted that pathetic fate (as any nation would), Israel has punished them for their insolence. This is not new.

Contrary to Netanyahu’s purposes, Khaled Elgindy argues, the war has united the Palestinian factions and made a third intifada more likely:

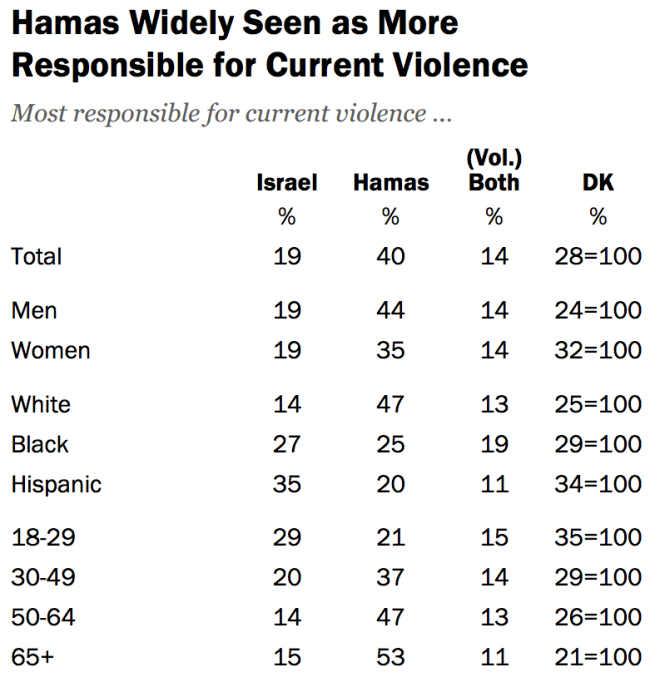

Hamas’ relative success on the battlefield has boosted the group’s popularity while highlighting Abbas’ perceived impotence. According to one recent poll, since the Gaza crisis began, popular support for Hamas has outstripped support for Fatah for the first time in several years. Even so, most Palestinians understand the limitations of engaging in armed struggle against a formidable military power like Israel. As a result, despite the recent collapse of U.S.-led peace talks, Abbas’ negotiations agenda remains relevant.

More significantly, the ongoing devastation in Gaza has forced all Palestinian factions for the first time in many years to close ranks on a major political issue (as opposed to procedural or administrative matters, which were at the heart of the recent reconciliation agreement). Indeed, one of Hamas’ chief demands was that Israel respect its reconciliation agreement with Fatah. During previous conflicts in Gaza, the leadership in the West Bank had been reluctant to side openly with Hamas. Those calculations clearly no longer apply.

But Steven Cook is not optimistic about the prospect of rescuing Abbas from irrelevance:

Almost from the start of the conflict in the Gaza Strip, the commentariat has been seized with the idea of “empowering [Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud] Abbas” as the only way out of the recurrent violence between Israel and Hamas. The discovery of this idea in Washington (and Jerusalem for that matter) is rather odd, not because it does not make sense, but rather because the idea is so reasonable and obvious that one wonders why — ten years after he became the Palestinian leader — it took so long to recognize it. Almost from the moment of Yasser Arafat’s death, Egypt sent high-level emissaries to the United States, warning that the new Palestinian president needed help lest he gradually cede the political arena to Hamas. He did not get it then and now it is likely too late to salvage Abbas. …

Over the last decade the combination of American and Israeli political pressure, missteps, and disingenuousness have consistently left the Palestinian president in a bind, forced to take part in negotiations that he and his advisors knew would never go anywhere, and then hung out to dry when they failed.

And that’s about as bullish as Michael Totten feels about the peace process:

Nobody can know how the next attempt will play out in detail, but none of the actors at this point is optimistic. And that’s without factoring Hamas into the equation, which rejects both negotiations and peace out of hand and vows to wage a decades- or even centuries-long war to the finish. Hamas will gleefully sacrifice a thousand Palestinian lives to kill a few dozen Israelis because its leaders truly believe that if life becomes too precarious and nerve-wracking for Jews in the Middle East that they’ll give up and quit the region forever. It’s a fantastical bloody delusion, but it’s what they believe and they are not going to stop any time soon.

I hate to be too cynical about this myself, but as I’ve said before, the Middle East is a great teacher of pessimism. A few years ago I asked Israeli writer and researcher Hillel Cohen what he expected to see in Jerusalem 50 years in the future. “Some war,” he said, shrugging. “Some peace. Some negotiations. The usual stuff.”

That niggling concern, that the peace process is finally dead, will be keeping political scientists busy long after this war is over, Marc Lynch predicts:

What happens if there is no peace process? There’s a plethora of articles about the vicissitudes of Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations, but far fewer on how to think about their absence. It has probably been more than a decade since anybody seriously believed in the possibility of a negotiated two-state solution, but most diplomats and pundits continue to go through the motions out of fear of contemplating the alternatives. After the failure of Secretary of State John Kerry’s team, it is hard to imagine anyone else putting much effort in to them any time soon.

Some long-standing assumptions seem ripe for testing. What happens now that peace talks seem unlikely to resume? What is the universe of comparable cases, and how did they end up? Is it really true that Israel cannot sustain the status quo indefinitely? Does the commonly-invoked tension between being a Jewish state and a democracy still really matter to Israelis, given the ongoing changes in Israel’s demographics and the shift rightward in its political culture?