Kara W. Swanson, author of Banking on the Body, contends that “the simple pay-suppliers/don’t-pay-suppliers approach to thinking about body products … needs to be replaced with more nuanced thinking”:

Should we treat different types of organs (hearts v. bone marrow) differently? Can we think about compensation schemes that are not free markets, but are managed to support the public goals of increasing body-product supply? Can those schemes protect suppliers and recipients alike by keeping suppliers safe from exploitation, and recipients safe from diseased products? I use history to suggest that the answers can sometimes be yes. Body products used to be routinely paid for, and doctors thought about these potential problems and addressed them. Over time, we have forgotten this past, and come to assume that buying body products is always dangerous and bad.

I like to remind people that lots of altruistic gestures are compensated—the doctors, and nurses, and everyone who works on a transplant operation are all in caring professions. They are doing those jobs because they want to help people (at least we hope and assume so). But we wouldn’t suggest that they shouldn’t be paid because to offer payment for such efforts would be insulting or immoral or cause their altruistic tendencies to be replaced by mercenary concerns.

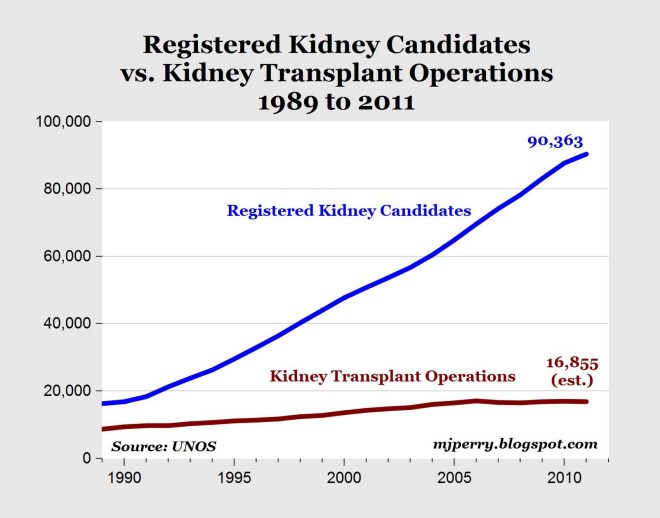

Yet that is how we treat organ supply—that offering money would do all those bad things. Why should the supplier of a body product be the only person in that life-saving supply chain who is not compensated? People might choose not to be compensated, but if they want to be, and if more folks will act as suppliers with that incentive, why not?

The Dish has covered these questions extensively over the years.