I’ve been reading various reports (like this one) of the success of a research group at MIT in taking the sting out of bad memories by switching the bad ones with good ones:

“In our day to day lives we encounter a variety of events and episodes that give positive or negative impact to our emotions,” said Susuma Tonegawa, Professor of Biology and Neuroscience at the Riken-MIT Centre for Neural Circuit Genetics.

“If you are mugged late at night in a dark alley you are terrified and have a strong fear memory and never want to go back to that alley.

“On the other hand if you have a great vacation, say on a Caribbean island, you also remember it for your lifetime and repeatedly recall that memory to enjoy the experience.

“So emotions are intimately associated with memory of past events. And yet the emotional value of the memory is malleable. Recalling a memory is not like playing a tape recorder. Rather it is like a creative process.

Granted, the experiments are on mice, but mouse models tend to transfer well-enough to humans that the scientists are hopeful that they are on to something useful. But will it be?

I realize this sounds crazy. Given the chance, who wouldn’t want to erase or in some way circumvent the memory of being mugged? And what about PTSD? The MIT group is hopeful that their technique, when applied to humans, will counter the effects of post traumatic stress.

If the MIT group fails, there still may be hope, courtesy of DARPA, the research arm of the Defense Department, which is developing an implantable chip that intended to lessen the effects of post traumatic stress. According to the Washington Post:

It’s part of the Obama administration’s larger “BRAIN Initiative,” which involves the National Institutes of Health, DARPA, the National Science Foundation and the Food and Drug Administration, among other organizations.

Officials say the BRAIN Initiative — which stands for Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies — includes a related DARPA effort to build new brain chips that will be able to predict moods to help treat post-traumatic stress. It’s known as the SUBNETS program, short for Systems-Based Neurotechnology for Emerging Therapies. Teams at both the University of California, San Francisco, and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston are involved.

“Instead of relying only on medication, we envision a closed-loop system that would work in concept like a tiny, intelligent pacemaker,” said Doug Weber, the program’s manager. “It would continually assess conditions and provide stimulus patterns tailored to help maintain healthy organ function, helping patients get healthy and stay healthy using their body’s own systems.”

(If I am a little suspicious of this technique, it may be because a few years ago, while writing about the use of virtual reality to help veterans overcome PTSD, I also learned that the military was interested in using the technique in the field, to get psychologically damaged soldiers quickly back into action, which seemed both dangerous and creepy to me.)

We are made of memories and formed by experience. I keep wondering what kind of people we would be, and what kind of world this would be, if when bad things happened we could erase them, or somehow make them sweet. Consider Anna Whiston-Donaldson, author of the just published memoir Rare Bird, whose 12-year-old son died in a freak accident, drowning during a rainstorm. One imagines what she’d wish for is that her son did not die, not that she didn’t remember it, and not, even, that it wasn’t as painful as it was. Wouldn’t that impair grieving? Wouldn’t it dishonor–for lack of a better word–her son? I am not presuming to know. I don’t know. But I do know that meaning comes from many places.

So here is my question: if you could forget or erase that bad thing that happened to you, whatever it is, would you? Another way of asking this question is this: how has that bad thing made you who you are? Is there value–not in grief, but in grieving?

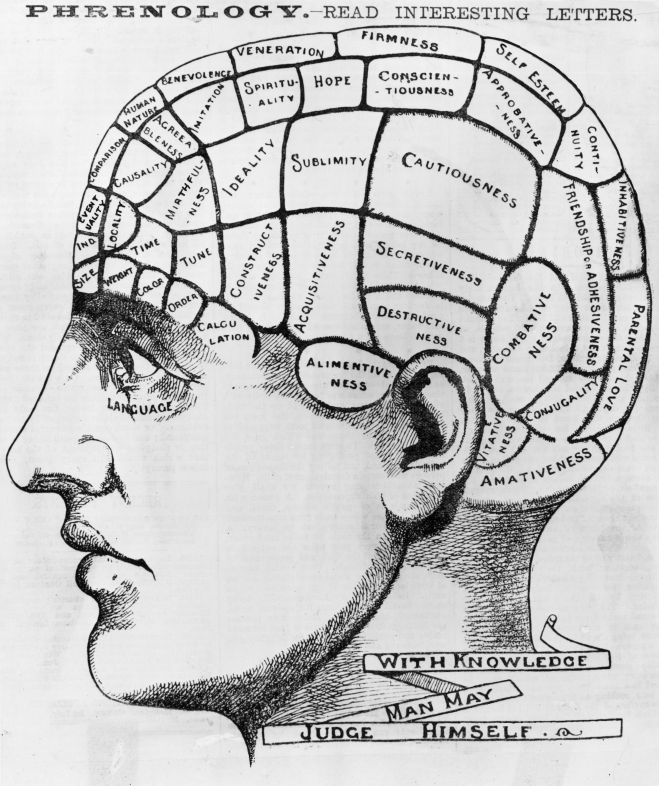

(Photo: circa 1880: A phrenological cross-section of a man’s head, illustrating the idea that the brain processes thoughts in different locations according to their type. By Hulton Archive/Getty Images)