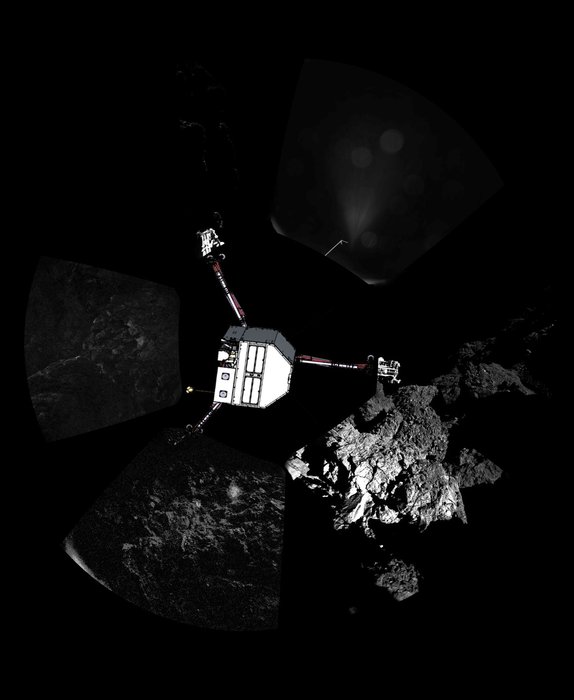

That’s how Jonathan Freedland describes the Rosetta space mission:

The narrow version of this point focuses on this as a European success story. When our daily news sees “Europe” only as the source of unwanted migrants or maddening regulation, Philae has offered an alternative vision; that Germany, Italy, France, Britain and others can achieve far more together than they could ever dream of alone. …

Even that, as I say, is to view it too narrowly. The US, through Nasa, is involved as well. And note the language attached to the hardware: the Rosetta satellite, the Ptolemy measuring instrument, the Osiris on-board camera, Philea itself – all imagery drawn from ancient Egypt. The spacecraft was named after the Rosetta stone, the discovery that unlocked hieroglyphics, as if to suggest a similar, if not greater, ambition: to decode the secrets of the universe. By evoking humankind’s ancient past, this is presented as a mission of the entire human race. There will be no flag planting on Comet 67P. As the Open University’s Jessica Hughes puts it, Philea, Rosetta and the rest “have become distant representatives of our shared, earthly heritage.”

That fits because this is how we experience such a moment: as a human triumph.

When we marvel at the numbers – a probe has travelled for 10 years, crossed those 4bn miles, landed on a comet speeding at 34,000mph and done so within two minutes of its planned arrival – we marvel at what our species is capable of. I can barely get past the communication: that Darmstadt is able to contact an object 300 million miles away, sending instructions, receiving pictures. I can’t get phone reception in my kitchen, yet the ESA can be in touch with a robot that lies far beyond Mars. Like watching Usain Bolt run or hearing Maria Callas sing, we find joy and exhilaration in the outer limits of human excellence.

And it’s a scrappy little lander:

Instead of landing on its planned target, Philae took a dramatic double bounce into the shadows of the comet, where only a tiny bit of sunlight can reach its solar panels. The battery, which lasts for two and a half days, was intended to power Philae during its first planned sequence of data collection. After the battery ran out, Philae was to rely on the sun.

Despite Philae’s precarious position on a cliff, it managed to collect all the data that mission controllers had planned for—images, information on the comet’s chemical composition and its surface properties, for example. The spacecraft even managed to drill into the comet’s surface. Mission controllers also rotated Philae 35 degrees in the hopes of getting its solar panels in a more favorable position. It remains to be seen whether the maneuver will pay off.

Joseph Stromberg explains the importance of comet research:

All this data is so valuable because the comet likely formed 4.6 billion years ago, from material leftover asEarth and the solar system’s other planets were coalescing. As a result, understanding the composition of this comet — and comets in general — could help us better model the formation of the solar system. Moreover, many scientists believe that in the period afterward, when the solar system was still a chaotic, collision-filled system, comets and asteroids were responsible for bringing water and perhaps even organic molecules to Earth. By analyzing data collected by Philae on ice and other substances on the comet’s surface, we could gather important clues as to whether the hypothesis is correct.

Rachel Feltman looks ahead:

Several missions in the near future will take us to asteroids, the slower-moving (and easier to chase down) cousins of comets. In 2016, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx will use a spacecraft with a robotic arm to pluck some asteroid off and take it home. And while we wait for another Philae-like comet trip – which probably won’t come in the next 10 years – we still have Rosetta. The spacecraft will follow its comet for a year, studying it as it passes the sun. And during that time, if enough light hits its solar panels, Philae could even make a comeback – reuniting the world’s new favorite pair of space buddies.

(Photo: Rosetta’s lander Philae has returned the first panoramic image from the surface of a comet. The view, unprocessed, as it has been captured by the CIVA-P imaging system, shows a 360º view around the point of final touchdown. By ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA)