by Jonah Shepp

#ISIS captures key #Syria army base #ISIS #Iraq – http://t.co/YobEyo95Jq. pic.twitter.com/qjNbYVuRyj

— Al Arabiya English (@AlArabiya_Eng) August 9, 2014

Aki Peritz believes that ISIS poses a genuine terrorist threat to the US, and on that basis, suspects that Obama will eventually see fit to target the group in Syria as well as Iraq:

It is well and good that the president said he won’t “rule out anything,” but the reality is that multiple jihadist groups already have a permanent foothold in Syria. … Will ISIL, or another Syria-based jihadi group, try to strike American targets before Obama leaves office in January 2017? If past actions predict future behavior, then the answer is probably yes. Would the administration respond to a terror attack on America or Americans with airstrikes—or perhaps more—of its own? That too is likely in the cards, given that the United States just bombed Islamic State positions to help our Kurdish allies.

Hopefully, America’s airstrikes near Irbil will prove to be the high-water mark for ISIL’s ability to export its fanatical ideology. But the group has shown itself to be an adaptable, ruthless foe bent on destroying its enemies—including the United States. Since that’s the case, it’s only a matter of time before this White House decides that America must strike Syria as well.

And maybe it will, but the argument that it should fails on two levels. First, if ISIS wants to attack Americans, deploying more American soldiers in its areas of operation makes the targeting of Americans more likely, not less (and creates a justification for it, at least in the militants’ own view). And second, if ISIS wants to carry out an attack on US soil, it won’t do so with the soldiers and materiel in Syria that Peritz would have us bomb. Rather, that threat would likely take the form of a few fanatics with American or European passports, and I don’t see how airstrikes would address that, short of killing every single ISIS member and sympathizer in Syria and Iraq (and not only there – Peritz might want to start ginning up support for airstrikes on London and New Jersey as well).

No, this conflict is not ultimately about US homeland security; it remains, first and foremost, a regional power struggle. Certainly, some of the Syrian rebels would like us to get involved:

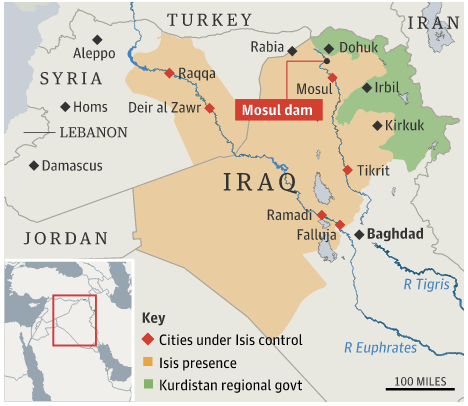

Moderate Syrian rebels argue that, in order to challenge ISIS in Iraq, it would be necessary to tackle them in Syria too. “To protect [the Iraqi city of] Irbil from ISIS, you need to hit ISIS hard in the Euphrates river valley in Syria,” said Oubai Shahbandar, spokesman for the opposition Syrian National Coalition. “Stopping ISIS expansion requires a ground game. U.S. needs to coordinate with the tribes and the Free Syrian Army that have been fighting ISIS since January.”

“Airstrikes won’t deny ISIS territorial gain,” Shahbandar said. “U.S. needs to support those forces like FSA and tribes in Syria already on the ground fighting ISIS.”

But others, Hassan Hassan reports, appear to have joined forces with the jihadists:

According to Samer al-Ani, an opposition media activist from Deir Ezzor, several fighting groups affiliated to the western-backed Military Council worked discreetly with Isis, even before the group’s latest offensive. Liwa al-Ansar and Liwa Jund al-Aziz, he said, pledged allegiance to Isis in secret, with reports that Isis is using them to put down a revolt by the Sha’itat tribe near the Iraqi border.

He warned that money being sent through members of the National Coalition to rebels in Deir Ezzor risks going to Isis. Another source from Deir Ezzor said that these groups pledged loyalty to Isis four months ago, so this was not forced as a result of Isis’s latest push, as happened elsewhere. Such collaboration was key to the takeover of Deir Ezzor in recent weeks, especially in areas where Isis could not defeat the local forces so easily.

This complication reveals how facile and ignorant the neo-neocon case for intervention in Syria is. Simply sussing out who our friends and enemies are within the fragmented rebel “coalition” has always been a much more daunting task than the hawks were willing to admit. We don’t have the intelligence to conduct such an intervention, well, intelligently, and there’s just no getting it now. Compare that to Iraq: it’s a mess, sure, but at least our friends (Kurds), enemies (ISIS), and liabilities (Baghdad) are much more clearly defined. That’s why Michael Totten finds the question in the headline of this post sort of boring:

The Kurds of Iraq are our best friends in the entire Muslim world. Not even an instinctive pacifist and non-interventionist like Barack Obama can stand aside and let them get slaughtered by lunatics so extreme than even Al Qaeda disowns them. There is no alternate universe where that’s going to happen. Iraqi Kurdistan is a friendly, civilized, high-functioning place. It’s the one part of Iraq that actually works and has a bright future ahead of it. Refusing to defend it would be like refusing to defend Poland, Taiwan, or Japan. We have no such obligation toward Syria.

That’s it. That’s the entire answer. Washington is following the first and oldest rule of foreign policy—reward your friends and punish your enemies.

In any case, ISIS’s positions in eastern Syria are already being bombed by the Assad regime, with much collateral damage:

Militants from the Al-Qaeda splinter group are fighting on a multitude of fronts in Syria’s complex civil war – against an array of rebel groups, regime forces, and the Kurdish YPG militia – while also being targeted by locals in the eastern province of Deir al-Zor. When ISIS entered Deir al-Zor last month, it seized a number of towns and villages along the Euphrates River, often by making agreements with locals. Since then, attacks have been staged against the jihadists, who have been accused of breaking their word and detaining residents of the area. Regime forces have only recently begun targeting ISIS positions in several provinces, while anti-regime activists say the strikes have led mainly to civilian casualties.

That’s another reason why, I suspect, Obama remains set against getting involved. A war of attrition between Assad and ISIS is very bad news for the Syrian people, but as soon as American bombs begin to fall, those civilian deaths accrue to us, and those terror attacks on Americans that Peritz fears start looking like a much more attractive option for ISIS and its allies.