A reader writes:

Wow. You’ve really dug yourself into a deep hole. The country of Syria was given its name by the Greeks before Alexander, and aside from its shifting borders, Syria has remained constant from Greek toRoman to Umayyad to Abbasid to Ottoman to Arab to French to Syrian rule. There  as even a Syrian Roman emperor in 244. If Syria isn’t a country, then neither is Turkey, the UK, or any other country. A few seconds on Wikipedia or with the classics confirms all this, with ancient maps of Syria that are as close to modern Syria as is Sykes-Picot’s or T.E. Lawrence’s maps. Compare the map of Roman Syria from the first century BC to the 19th century map of Ottoman Syria. Aside from Palestine, they’re the same province, which is now the same country.

as even a Syrian Roman emperor in 244. If Syria isn’t a country, then neither is Turkey, the UK, or any other country. A few seconds on Wikipedia or with the classics confirms all this, with ancient maps of Syria that are as close to modern Syria as is Sykes-Picot’s or T.E. Lawrence’s maps. Compare the map of Roman Syria from the first century BC to the 19th century map of Ottoman Syria. Aside from Palestine, they’re the same province, which is now the same country.

And the theory (which is yours) that the Ottomans gave the minority Shia and Christians “pools of self-governance” and that modern Syria “was precisely constructed to pit a minority … against the majority” is all absurd non-history. Both the Ottomans and the French protected their minority sects, but neither gave them self-governance or control over the majority. The straight line you draw from Sykes-Picot to brutal al-Assad rule does not exist. What’s more, and ironic for your argument, the very name of the al-Assad family comes from Hafez’s father’s opposition to modern Syria! The Syrian military coups that happened 40 years later that ultimately led to Alawite dominance have nothing to do with Sykes-Picot.

There are of course excellent reasons to avoid a foreign entanglement in a sectarian civil war, but unfortunately you’ve badly mangled history and logic to make this point.

It is not “absurd non-history” to note that modern Syria is comprised of a complex mix of extremely different sectarian and ethnic groups who have fought each other for a very long time, and that under French colonial rule, the Alawites were the favored sect. In independent Syria, the Alawites gained real power especially through the military, and ran the country under the Assad dynasty as a deeply sectarian, Shi’a force against the majority Sunni. That also explains their alliance with Iran, the region’s major Shiite power, if you don’t include post-Saddam Iraq. That dynamic means that Syria as a modern state is inherently unstable, unless sectarian identity recedes (fat chance after two years of brutal civil war), and was designed to be inherently unstable. Again, my point was not that Syria is not a name that was attached to the entire region, but that as a unitary state, in its current borders, it is a colonial contraption unfitted to multi-sectarian self-government. Another informed reader:

I have a Ph.D in anthropology and spent decades working in Syria both with archaeological projects (for fun) and as a researcher in social anthropology studying contemporary society in Syria. I was also a Fulbright Fellow there. Anyway, I have not only read immense amounts of Middle Eastern history but lived at archaeological projects out in the Syria Jazeera as well as done ethnographic research in Damascus. I stumbled on this insight as a grad student (and as some one who had to take long-haul buses around the country). I largely agree with your post on Syria.

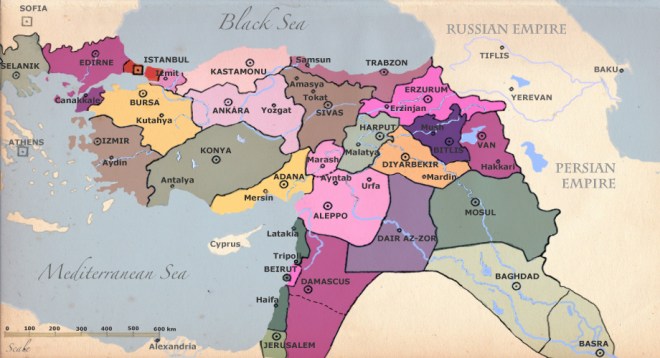

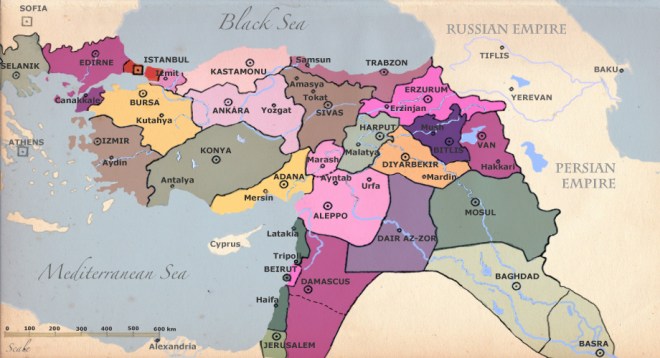

Any potential natural “nations” (of course, all nation states are largely imaginary) of the Middle East can best be found in the old Ottoman provinces, which were much more closely aligned with communities of common interest than the Sykes-Picot nation-states. Of the course the Brits/French pissed all over those separations and alliances. Which is the problem.

You should get some true Ottoman scholars to chime in – I am not an Ottoman expert. Also, it’s hard to find a good online map with the detail needed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the best I found is from an Armenian advocacy group which has a vested interest in understanding the administrative units of the Ottoman Empires:

But the Ottomans ran a big empire and the provinces were created to make administration easier. So they tended to fall along natural lines of communication with rivers, mountain passes, changes in elevation or whether or not the land was agricultural or only suited for grazing determining what was part of one province and what areas belonged to another. The Ottoman Empire was in existence for a long time and the provincial borders were fluid and changed over time and were often subdivided into smaller units and these sub-units often had governors drawn from the local population. So the province of Mosul was always quite independent, more likely than not to have locals in administration. Before naval power made control of harbors key, the Ottoman province of Basra might have had a local Arab leader. Once the British peeled away Kuwait in 1899 when it became a protectorate, then Basra became more important to the Ottomans and had rulers sent directly from the capital.

Anyway, the Sikes-Picot treaty collected the Ottoman provinces of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul into Iraq. Just the part of Mosul that possibly had oil made it into Iraq. Much of its hinterland was sliced away and left in what would become Syria. What is now northeastern Syria – and seems to be largely under the control of the Syrian Kurds at the moment – largely traded with Mosul and Aleppo to the east and west with some trade down the Khabur river to Deir-ez-Zor. These are areas that have been linked by trade since the empires of ancient Mesopotamia! These areas have always contained tremendous ethnic and religious diversity (Arab Sunni Muslim, Arab Shia Muslim, Chaldean and Assyrian Christian, Jews – of both Arab and Kurdish ethnicity – Armenian Christians, Yazidis, as well as tribal structures that often divided and reunited these areas in surprising ways) but the natural landforms united these areas as trading partners. You can see this in the patterns of the Akkadian and Babylonian Empires as well as in the route of the Berlin-Baghdad Railroad!

Notice the southern part of the route with stations in Aleppo, Nusaybin, Mosul, Baghdad, then Basra. That’s the unit in which common economic interest and trade patterns allowed diverse populations to work together. That’s what Sikes-Picot cut apart. Notice also that Damascus, Jerusalem, Beirut, Latakia are not part of that economic/trade cluster at all. Damascus (es-Sham) and its immediate countryside was cut off from the broader territory that made up the Ottoman province of es-Sham by Sikes-Picot too. Even in the 1990s, many more buses ran each day from el-Hasake to Aleppo than from el-Hasake to Damascus, and the bus would only fill up after reaching Deir-ez-Zor.

The Ottoman provinces make more sense because pre-modern limits of communications divided the territories not European interests. The diversity of the population within the Ottoman provinces were often able to work together peacefully because they shared a common economic interest. Sikes-Picot severed and distorted those ties. One quick example, the division of Nisibis, an ancient and prosperous city, into the Turkish city of Nusaybin and the Syrian city of Qamishli. Read its history. The idea that Turkish or Syrian nationalism is strong enough to pull this city apart into two nations is laughable. Yet an international border divides it.

The terror (and the hope) of the civil war in Syria has always been that the country would come apart and with it the punishing dividing lines of Sikes-Picot.

That may be necessary for the Middle East to recover from the toll of colonialism. But it will take a lot of time and probably a lot of blood. It seems insane to me that a distant super-power should be involved in mediating something we cannot even begin to fully understand, let alone control. That fact alone buttresses the case for leaving it to its own devices.

Update from a reader:

I’ve been following the debate with interest. It seems to me that is the perfect opportunity to have someone who REALLY knows this history weigh in. In particular my good friend Scott Anderson, author of Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East, currently on the NYT bestseller list. Scott has fascinating stories to tell, as the many amazingly great reviews have noted [here, here, here].

as even a Syrian Roman emperor in 244. If Syria isn’t a country, then neither is Turkey, the UK, or any other country. A few seconds on Wikipedia or with the classics confirms all this, with ancient maps of Syria that are as close to modern Syria as is Sykes-Picot’s or T.E. Lawrence’s maps. Compare the

as even a Syrian Roman emperor in 244. If Syria isn’t a country, then neither is Turkey, the UK, or any other country. A few seconds on Wikipedia or with the classics confirms all this, with ancient maps of Syria that are as close to modern Syria as is Sykes-Picot’s or T.E. Lawrence’s maps. Compare the