The next couple of weeks will be full of surprises, twists and turns, as this country debates in its Congress and media and living rooms whether to launch another war in the Middle East. But I think it’s fair to offer a preliminary assessment of where the wind is blowing. Obama’s case for war is disintegrating fast. And his insistence on a new war – against much of the world and 60 percent of Americans – is easily his biggest misjudgment since taking office. His options now are not whether to go to war or not, but simply whether he has the strength and sense to stand down and save his second term before it is too late.

Here’s what we know now for sure already: even if the president were somehow to get a majority in House and Senate for entering into  Syria’s vortex of sectarian violence, it will be a profoundly divided one. The 10-7 vote in the most elite body – the Senate Foreign Relations committee – is an awful omen. To make matters worse, there is currently a clear national majority against war in the polls and the signs from the Congress suggest a nail-biter at best for the president. Under these circumstances, no president of any party has any right or standing to take this country to war. He is not a dictator. He is a president. Wars are extremely hazardous exercises with unknown consequences that require fortitude and constancy from the public paying for them. Even with huge initial public support for war, as we discovered in the nightmare years of Bush-Cheney, that can quickly turn to ashes, as reality emerges. To go to war like this would be an act of extreme presidential irresponsibility.

Syria’s vortex of sectarian violence, it will be a profoundly divided one. The 10-7 vote in the most elite body – the Senate Foreign Relations committee – is an awful omen. To make matters worse, there is currently a clear national majority against war in the polls and the signs from the Congress suggest a nail-biter at best for the president. Under these circumstances, no president of any party has any right or standing to take this country to war. He is not a dictator. He is a president. Wars are extremely hazardous exercises with unknown consequences that require fortitude and constancy from the public paying for them. Even with huge initial public support for war, as we discovered in the nightmare years of Bush-Cheney, that can quickly turn to ashes, as reality emerges. To go to war like this would be an act of extreme presidential irresponsibility.

And on one thing, McCain is right. To launch strikes to make a point is not a military or political strategy. It will likely strengthen Assad as he brazenly withstands an attack from the “super-power” and it would not stop him using chemical weapons again to prove his triumph. We either lose face by not striking now or we will lose face by not striking later again and again – after the initial campaign has subsided and Assad uses chemical weapons again. McCain’s response, as always, is to jump into the fight with guns blazing and undertake a grueling mission for regime change. Let him make that case if he wants – it is as coherent as it is quite mad. It’s as mad as picking a former half-term delusional governor as his vice-president. There is a reason he lost the election to Obama. So why is Obama now ceding foreign policy to this hot-headed buffoon?

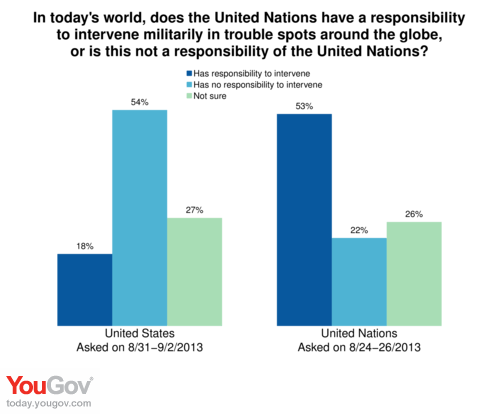

The only conceivable way to truly punish Assad and assert international norms would be to get a UN Resolution authorizing it. That is, by definition, the venue for the enforcement of international norms. The US Congress cannot speak for China or Russia, Germany or Britain. And in Britain’s case, the people – through their representatives – have spoken for themselves. That means that, if we go through the proper route, nothing will be done. But that is the world’s responsibility, not ours’. And we are not the world.

The US has no vital interests at stake in the outcome of a brutal struggle between Sunni Jihadists and Alawite thugs. None. Increasingly, as we gain energy independence, we will be able to leave that region to its own insane devices. Our only true interest is Saudi oil. And they will keep selling it whatever happens. Israel is a burden and certainly not an asset in our foreign policy. The obsession with the Middle East is increasingly a deranged one. Taking it upon ourselves to ensure that international norms of decency are enforced in that hell-hole is an act of both hubris and delusion. We can wish democrats and secularists well. But we can control nothing of their struggle, as the last few years have definitively shown. And when we try, we create as many problems as we may solve. Look at Libya.

My own fervent hope is that this is the moment when the people of America stand up and tell their president no.

I support and admire this president and understand that this impulsive, foolish, reckless decision was motivated by deep and justified moral concern. But the proposal is so riddled with danger, so ineffective in any tangible way (even if it succeeds!), and so divorced from the broader reality of an America beset by a deep fiscal crisis, a huge new experiment in universal healthcare, and a potential landmark change in immigration reform, that it simply must not be allowed to happen.

We can stop it. And if Obama is as smart as we all think he is, he should respond to Congress’s refusal to support him by acquiescing to their request. That would damage him some more – but that damage has been done already. It pales compared with the damage caused by prosecuting an unwinnable war while forfeiting much of your domestic agenda.

This is not about Obama. It’s about America, and America’s pressing needs at home. It’s also about re-balancing the presidency away from imperialism. If a president proposes a war and gets a vote in Congress and loses, then we have truly made a first, proud step in reining in the too-powerful executive branch and its intelligence, surveillance and military complex.

In other words, much good can still come from this.

If Congress turns Obama down – as it should – Obama can still go to the UN and present evidence again and again of what Assad is doing. Putin is then put on the defensive, as he should be. You haven’t abandoned the core position against the use of chemical arms, and you have repeatedly urged the UN to do something. Isn’t that kind of thing what Samantha Power longs for? Make her use her post to cajole, embarrass, and shame Russia and China in their easy enabling of these vile weapons. Regain the initiative. And set a UN path to control Iran’s WMD program as well.

Obama once said his model in foreign policy was George H W Bush. And that president, in the first Gulf War, offers a sterling example of how the US should act: not as a bully or a leader, but a cajoler, a facilitator and, with strong domestic and international support, enabler of resistance to these tin-pot Arab lunatics. Obama, in a very rare moment, panicked. What he needs to do now is take a deep breath, and let the people of this country have their say.

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A.