An interview with the sparkling, gregarious lady who won the Sarah Palin lunch – for $63,500. Fox and Friends say that a journalist who wanted to use the dinner to ask some tough questions was seeking to "defame" Palin.

Month: September 2009

The Case For More War

Les Gelb puts the case succinctly:

Even though I strongly believe that the United States does not have vital interests in Afghanistan, I also believe that Mr. Obama can't simply walk away from the war.

Note that Gelb strongly believes this war advances no real vital interests for the US. And yet he wants to send thousands more young Americans to fight there. He recommends Vietnamization Afghanization of the effort. Like we haven't tried that already. And then he simply splits the difference between what's really needed (long-term neo-imperial occupation) and what can be gotten past the American public. I.e.: two or three more years to save face.

If this is the best the pro-war forces can do, we should leave very soon.

For Want Of The Pill

DiA passes along a study:

The highest population growth rates in the world are currently found in the countries that have the least resources to sustain larger populations: Niger, Kenya, Afghanistan. More people means more consumption of limited resources and more emission of carbon dioxide. Helping people who want smaller families to prevent unwanted births would mean less emission of carbon dioxide. Last week, the Optimum Population Trust published a paper it had commissioned from the London School of Economics estimating the effect on carbon emissions of providing birth control to women who want to use it, but currently lack access. It found that spending on birth control is six times as effective, as a means of reducing carbon emissions, as spending on renewable energy.

Obama’s Key Ally On The Public Option

Bill O'Reilly. He is more attuned the actual needs and fears of some working Americans than the more ideological tools at Fox. The key TV endorsement after the jump:

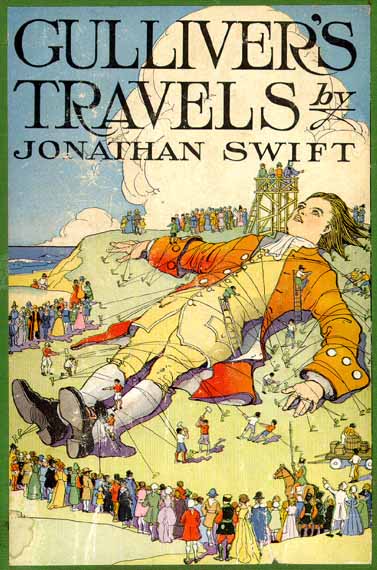

Gulliver In Afghanistan, Ctd.

Andrew Exum praises Steven Biddle's testimony from last week in favor of continuing the war in Afghanistan:

Andrew Exum praises Steven Biddle's testimony from last week in favor of continuing the war in Afghanistan:

I know some of my friends opposed to this war are frustrated with me at

the moment, but in all fairness, I'm frustrated with them too. No one can accuse me of glossing over the difficulties of the war in Afghanistan on this blog, but I have heard very few people make the case against the war while admitting that withdrawal might carry with it serious costs or that those who think the war is in the U.S. interest at the moment might have some evidence on their side as well. (And it's not an either/or debate, right? There might be operational choices other than COIN that safeguard U.S. interests. But those who would advocate those choices owe it to us to operationalize them and show us what they would look like on the ground as well as what risks they would run.)

Biddle's argument runs all of eleven pages and is well worth a read. He sees Pakistan as the core reason to stay in Afghanistan. A snippet:

The Taliban are a transnational Pashtun movement that is active on either side of the Durand Line and sympathetic to other Pakistani Islamist insurgents. Their presence within Pakistan is thus already an important threat to the regime in Islamabad. But if the Taliban regained control of the Afghan state or even a major fraction of it, their ability to use even a poor state’s resources as a base to destabilize secular government in Pakistan would enable a major increase in the risk of state collapse there. Much has been made of the threat Pakistani base camps pose to Afghan government stability, but this danger works both ways: instability in Afghanistan poses a serious threat to secular civilian government in Pakistan. And this is the single greatest stake the United States has in Afghanistan: to prevent it from aggravating Pakistan’s internal problems and magnifying the danger of an al Qaeda nuclear sanctuary there.

But doesn't this beg the question of why Pakistan cannot hold together and resist this kind of insurgency from a backward country on its borders. Why exactly is it America's job to prevent two vast countries and millions of people from saving themselves from Taliban extremism? At what point does anyone actually have the gumption to say: this cannot be done.

We are treating these countries like welfare recipients. And we clearly need welfare reform.

Yglesias Award Nominee

“I am not going to give into sentiments that I think degrade the office of the president and that degrade the debate and the culture of our country. So if you come up to me calling the president a socialist, a Muslim, you’re talking to the wrong guy," – Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC).

(Hat tip: Matt Corley)

The Delayed Debate

Tom Ricks highlights the following part of George Packer's article on Afghanistan and Richard Holbrooke:

[Y]ou want open airing of views and opinions and suggestions upward, but once the policy's decided you want rigorous, disciplined implementation of it. And very often in the government the exact opposite happens. People sit in a room, they don't air their real differences a false and sloppy consensus papers over those underlying differences, and they go back to their offices and continue to work at cross purposes, even actively undermining each other.

Ricks calls this "a pretty good summary of the Bush Administration's handling of Iraq, 2002-2006."

Reality Check

According to a new poll by the Des Moine Register, 92 percent of Iowans say that gay marriage “has brought no real change to their lives.”

Taking Fire From Both Sides

Jon Cohn blames "the almost total lack of approving commentary " for the unpopularity of the stimulus. He thinks the same thing could happen to health care:

Liberal Democrats in Congress understand that they won’t have any leverage unless they can credibly claim to vote against reform that falls short of their ideal. This requires them to say things like “health care reform without a public plan is not reform.” It becomes a problem if enough people actually believe their own bluff.

Classism At Its Worst

The Onion reports on the nouveau poor.