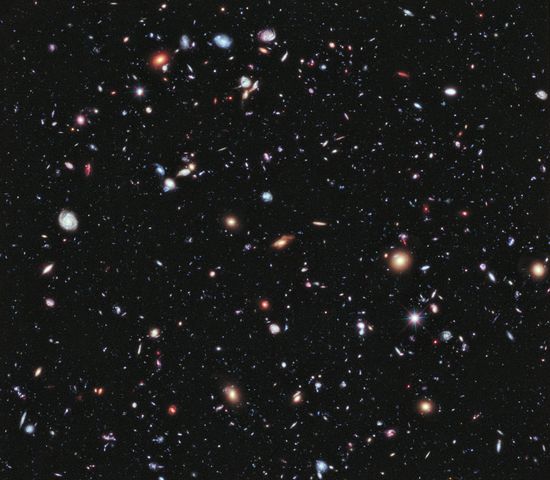

Space.com rounds up their favorite images from 2012, among them the farthest-ever view of the universe as captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, showing an incredible 5,500 galaxies:

Clara Moskowitz explained the image when it was released back in September:

The picture, called eXtreme Deep Field, or XDF [link], combines 10 years of Hubble telescope views of one patch of sky. Only the accumulated light gathered over so many observation sessions can reveal such distant objects, some of which are one ten-billionth the brightness that the human eye can see. The photo is a sequel to the original "Hubble Ultra Deep Field," a picture the Hubble Space Telescope took in 2003 and 2004 that collected light over many hours to reveal thousands of distant galaxies in what was the deepest view of the universe so far. The XDF goes even farther, peering back 13.2 billion years into the universe's past. The universe is thought to be about 13.7 billion years old.

Phil Plait marvels at the "variety of galaxies":

Some look like relatively normal spirals and ellipticals, but you can see some that are clearly distorted due to interactions – collisions on a galactic scale! – and others that look like galaxy fragments. These may very well be baby galaxies caught in the act of forming, growing. The most distant objects here are over 13 billion light years away, and we see them when they were only 500 million years old. In case your head is not asplodey from all this, I’ll note that the faintest objects in this picture are at 31st magnitude: the faintest star you can see with your naked eye is ten billion times brighter. …

We humans, our planet, our Sun, our galaxy, are so small as to be impossible to describe on this sort of scale, and that’s a good perspective to have. But never forget: we figured this out. Our curiosity led us to build bigger and better telescopes, to design computers and mathematics to analyze the images from those devices, and to better understand the Universe we live in.