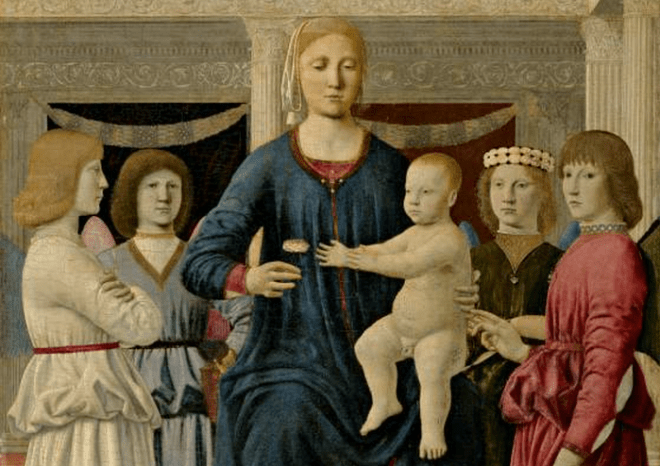

This weekend on the Dish, we provided our usual eclectic coverage of religious, books, and cultural coverage. In matter of faith, doubt, and philosophy, Conor Williams pondered the miracles that come from love, J.L. Wall examined an exception to the decline of the religious novel, and Kerry Howley imagined a conversation between Schopenhauer and Joel Osteen. Christian Wiman ruminated on the parables of Jesus, Jerry Saltz praised Piero della Francesca’s artistic vision, and Stefany Anne Golberg visited the Shaker Heritage Society in New York. Alan Jacobs remembered Walker Percy’s Lost in the Cosmos, readers debated arguments against polygamy, Robert Zarestksy argued that Isaiah Berlin thought like a fox, and Kiley Hamlin asked why we judge each other.

In literary coverage, W.H. Auden critiqued the gluttony of reading, Amit Majmudar found that contemporary fiction fears sentimentality, and John Fram described writing a bad book for money. John Jeremiah Sullivan movingly recalled his father’s love, Jason Resnikoff traced the evolution of the word “indescribable,” and Carmel Lobello provided a Scrabble player’s dream. Claire Barliant highlighted a library of unborrowed books, Cynthia L. Haven explored how Polish-born poet Czesław Miłosz’s became a Californian, and Mark Levine mused on what former Poet Laureate Philip Levine was like in the seminar room. Mark Oppenheimer gave tips on freelancing in the digital age, Julian Baggini held that encyclopedias always were relics, and Simon Akam mourned the distinctly American transformation of a butchered pun. Read Saturday’s poem here and Sunday’s here.

In assorted news and views, Maggie Koerth-Baker compared gun violence to climate change, Marc Tracy showed where Moneyball is bankrupt, and Chip Scanlan emphasized the power of silence for journalists conducting interviews. There proved to be an app for STD diagnosis, Conner Habib critiqued Alain de Botton’s views on sex, and Rose Surnow detailed the market for paying for cuddling. Marina Galperina gazed at webcam performers who pose like they’re in a classic work of art, Niall Connolly delved into the history and enduring popularity of “voguing,” Tom Junod looked back at Dazed and Confused, and Megan Garber cast a light on moon towers.

MHBs here and here, FOTDs here and here, VFYWs here and here, and the latest window contest here.

– M.S.

(Image: Detail of Piero della Francesca’s “Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels”)