“I’m a WWE superstar and to be honest with you, I’ll tell you right now, I’m gay. And I’m happy, very happy. To be honest, I don’t think it matters. Does it matter? Does it matter to you? Does it change what you think about me? I guess if you want to call it coming out; I really don’t know what to say it is but I’m just letting you know. I’m happy with who I am, I’m comfortable with myself, and I’m happy to be living the dream,” – Darren Young, pro wrestler.

Month: August 2013

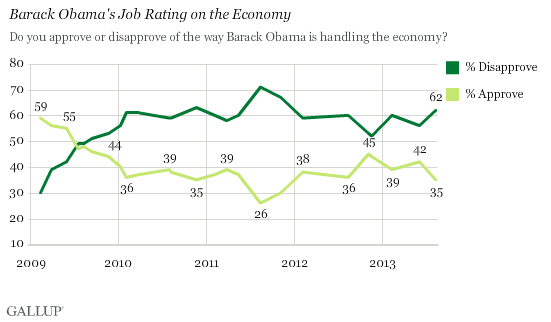

Obama And The Economy

The news from Gallup cannot be buoying the president in yet another summer swoon. Approval of his economic performance is back to near 2011 levels:

How to account for this, when the economy is actually growing again, and when the US recovery has been more powerful than any other developed country? I’d say a few things: the simple fact that he cannot truly execute his economic policy as long as the GOP controls the House and blocks new infrastructure spending and mandates a sequester that has both cut the deficit but also dampened growth; the lack of good new jobs for vast swathes of the middle class stranded after the banking crisis (hence the sharp decline in white working-class support); and the anemic level of growth that has done little to recoup the huge losses of the recession.

How to account for this, when the economy is actually growing again, and when the US recovery has been more powerful than any other developed country? I’d say a few things: the simple fact that he cannot truly execute his economic policy as long as the GOP controls the House and blocks new infrastructure spending and mandates a sequester that has both cut the deficit but also dampened growth; the lack of good new jobs for vast swathes of the middle class stranded after the banking crisis (hence the sharp decline in white working-class support); and the anemic level of growth that has done little to recoup the huge losses of the recession.

Voters gave Obama enough time to get things back on track, and they’re not happy with the track. And why should they be? Obama can say the Congress and state governments have foiled him – but, in the end, the GOP’s cynical strategy appears to be working: sabotage the economy so Obama gets all the blame, and cling on to whiter and whiter districts to keep the obstruction going, and keep growth low. That the GOP’s alternative economic plans are either Randian dreams or austerity-on-steroids does not matter as long as they are not in power. Oppositionism is all they need for now.

But there are long-term reasons why this assessment may be far too gloomy. Growth is accelerating somewhat; the deficit is falling fast; unemployment looks set to fall still further. The GOP may well blow its cynical strategy and favor a showdown over spending with Obama this fall. The result of that epic shoot-out will probably shift the political climate more powerfully than any poll can indicate now. But at some point, in any case, if the GOP seems set on governing, its own alternatives will rise to the surface. We saw what happened to Paul Ryan’s budget once it had to be attached to a national ticket: it was basically junked, and even then, he lost. So we wait and see.

But the main reason why Obama’s economic approval isn’t doomed is, in my view, simpler.

Here’s a piece from the British Tory paper, the Telegraph, that explains why. It follows conservative economics when in power from the vantage point of the Coalition government in Britain. And it shows that full-bore austerians, when actually forced to govern a country, rather than simply launch an opposition, have conceded much of the argument to Obama’s pragmatic legacy. It is Obama who is now the model for much of Europe, after excessive austerity along GOP lines proved disastrous. Money quote:

In claiming to be “fiscal conservatives but monetary activists”, Britain’s Tory leadership seem broadly to have returned to a Friedmanite path. In a half-hearted sort of way, David Cameron wants to shrink the state – but he also thinks monetary intervention can counter the adverse consequences on demand. There is also lip-service paid to Hayek, with a little dabbling in supply-side reform.

The Coalition has thus ended up with what used to be called the “neoclassical synthesis” – adherence to the basic principles of laissez-faire economics, but with a bit of Friedman, Keynes and even Hayek thrown in. In this sense, the crisis hasn’t changed the prevailing economic orthodoxy very much, since this is basically the thinking that has instructed policy-making for half a century or more.

What may now be true of Britain is even more so of the US, where leaders have from the start adopted a fundamentally pragmatic approach to the crisis. Rather than let ideology rule, America has focused more on what’s proven to work. The result has been a much swifter, albeit still not entirely secure, recovery. Belatedly, the Coalition seems to be following its lead. What took it so long?

Obama has always been a pragmatist (not a leftist) in economics, and I’d argue that his response to the Great Recession was easily the best of any Western leader because of it. Maybe this isn’t clear now; but in the end, it will be and is already validated by the evidence. I believe that, in the end, that evidence will be critical, if Obama can deploy it effectively to make his case. And in the context of the strongest growth among Western developed countries, he can.

Egypt On The Edge

Rabaa Square is no more #Egypt via Raba’a Group page pic.twitter.com/RYb3SB79o9

— Ayman Mohyeldin (@AymanM) August 15, 2013

My childhood friend, Ahmed Ali Sonbol, got killed yesterday. He was not a terrorist. pic.twitter.com/SSS3SHZyM3

— الإِسْكَنْدَرَانَيّة (@_Schehrazade_) August 15, 2013

Juan Cole analyzes the situation:

Although al-Sisi said he recognized an interim civilian president, supreme court chief justice Adly Mansour, and although a civilian prime minister and cabinet was put in place to oversee a transition to new elections, al-Sisi is in charge. It is a junta, bent on uprooting the Muslim Brotherhood. Without buy-in from the Brotherhood, there can be no democratic transition in Egypt. And after Black Wednesday, there is unlikely to be such buy-in, perhaps for a very long time. Wednesday’s massacre may have been intended to forestall Brotherhood participation in civil politics. Perhaps the generals even hope the Brotherhood will turn to terrorism, providing a pretext for their destruction.

Paul Pillar has the same thought:

Wouldn’t the breeding of more Egyptian terrorists be a bad thing from the viewpoint of Egyptian military leaders? Not if they wish to present themselves as a bastion against terrorism and to lay claim as such to American support.

Larison adds:

Of course, it is perverse to consider the military a “bastion” against a threat that their actions are making worse, but this will probably be accepted here in the U.S. as a “necessary” arrangement.

Instead of doing our best to disentangle the U.S. from our ties to the leaders of the coup, which seems the only sane thing to do at this point, Washington will find new excuses for why this week’s disaster requires even more “engagement” than before.

Issandr El Amrani worries about a militarized Muslim Brotherhood:

An Islamist camp that, as elements of it are apparently beginning to, sets fire to churches and attacks police stations is one that becomes much easier to demonize domestically and internationally. But it is also much more unpredictable than Egypt’s homegrown violent Islamist movements were in the 1980s and 1990s, because there is a context of a globalized jihadi movement that barely existed then, and because the region as a whole is turmoil and Egypt’s borders are not nearly as well controlled as they were then (and today’s Libya is a far less reliable neighbor than even the erratic Colonel Qadhafi was then.)

Shadi Hamid fears that Egypt’s military junta will prove worse than Mubarak:

Democratic transitions, even in the best of circumstances, are uneven, painful affairs. But it no longer makes much sense to say that Egypt is in such a transition. Even in the unlikely event that political violence somehow ceases, the changes ushered in by the July 3 military coup and its aftermath will be exceedingly difficult to reverse. The army’s interventionist role in politics has become entrenched. Rather than at least pretending to rise above politics, the military and other state bodies have become explicitly partisan institutions. This will only exacerbate societal conflict in a deeply polarized country. Continuous civil conflict, in turn, will be used to justify permanent war against an array of internal and foreign enemies, both real and imagined.

Cook thinks that both the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian military have imitated the Mubarak regime:

Just as Egypt’s political system before the January 25 uprising was rigged in favor of Mubarak and his constituents, the Brothers sought to stack the new order in their favor, and today’s winners will build a political system that reflects their interests. This is neither surprising nor sui generis. In the United States, rules, regulations, and laws are a function of the powerful, too. But in America, the capacity for change exists; whereas in Egypt, those institutions are absent. Although virtually all political actors have leveraged the language of political reform and espoused liberal ideas, they have nevertheless sought to wield power through exclusion. This has created an environment in which the losers do not process their grievances through elections, parliamentary debate, consensus-building, and compromise — but through military intervention and street protests. This plays into the hands of those powerful groups embedded within the state who have worked to restore the old order almost from the time that Hosni Mubarak stepped down into ignominy two and a half years ago.

Peter Hessler likewise focuses on the effect of Egypt’s past regimes:

In Egypt, the current conflict reflects the vastly different responses that groups can have to a fledgling democracy after decades of dictatorship. For the Brotherhood, this means stubbornly following what it believes to be the correct and legitimate political path, even if it alienates others and leads to disaster; for the military, it’s a matter of implementing the worst instincts of the majority. In each case, one can recognize a seed of democratic instinct, but it’s grown in twisted ways, because the political and social environment was damaged by the regimes of the past half-century.

The Conflict Within Israel’s 1967 Borders

Beinart argues that a Palestinian state wouldn’t end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict:

For Netanyahu, the creation of a Palestinian state must mean the end of Palestinian claims against Israel. But there’s a problem. Even if Israel relinquishes the West Bank, it will still contain more than a million Palestinians. Jews generally call these folks “Israeli Arabs.” But surveys suggest that they increasingly call themselves “Palestinian” citizens of Israel. And even after the creation of a Palestinian state, they’ll have claims.

Israel’s Palestinian citizens don’t want to leave. Over the decades they have developed an identity distinct from their West Bank and Gazan cousins. They appreciate living in a prosperous, democratic country. But—and this is what keeps Netanyahu up at night—they don’t want that country to be a Jewish state (PDF).

They don’t feel warm and fuzzy about a flag with a Jewish star and a national anthem that talks about the “Jewish soul.” They believe, as a high-profile Israeli government commission acknowledged in 2003, that Israel’s treatment of them “has been primarily neglectful and discriminatory.” Their kids can’t aspire to be prime minister. In ways both deeply symbolic and highly practical, they feel like second-class citizens as non-Jews in a Jewish state.

For Zionists who believe in the legitimacy of a state that protects and represents the Jewish people—and I’m one of them—the opposition of Israel’s Palestinian citizens to Israel’s Jewish identity is a profound challenge. Netanyahu wants Abbas to solve it for him. That’s the real agenda behind his insistence that Abbas recognize Israel as a Jewish state. But Abbas can’t solve Netanyahu’s problem. Politically, he can’t accept something the Palestinians living inside Israel don’t. And even if he did, all he’d do is alienate himself from Israel’s Palestinian citizens. He wouldn’t make them feel less alienated from Israel’s anthem and flag.

Zionism always had an element of utopianism to it. But it is not in any way pleasant to observe the long-term consequences of such a radical experiment.

The View From Your Window

Terrorists On Twitter

The site’s recommendations engine is a boon for al Qaeda recruiters:

Let’s say your interest in terrorism was sparked by al Qaeda’s newest affiliate, the Syrian group Jabhat al-Nusra. So you follow their well-publicized Twitter account. … Armed with its knowledge of your interest in terrorism, Twitter slowly moves the Lady Gagas and Justin Biebers down the list [of recommended accounts], while moving hardcore terrorists and extremists higher and higher. Twitter’s recommendations are the cream of the crop, all the essential accounts a budding terrorist might want to discover. But it’s not just the low-hanging fruit. The more focused your initial follows are, the more specific the recommendations. Further experimentation shows that if you know one honest-to-God terrorist online, Twitter will cheerfully connect you with many others.

And it’s not just jihadists. Following the American Nazi Party serves up an equally compelling menu of white supremacists, anti-Semites, and violent terrorist groups. It doesn’t matter what twisted ideology you’re interested in, Twitter is there to help you get connected.

But al-Qaeda isn’t totally up on its social media savvy:

Last night, an al Qaeda affiliate asked its loyal Twitter followers for suggestions to help with Public Relations, and the Twitter hive mind answered. A linguist fluent in Arabic tells Business Insider the original hashtag translated to “#Suggestions_to_Develop_Jihadist_Media”. J.M. Berger, a counter terrorism expert who wrote the book “Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go To War In The Name Of Jihad,” started the trolling with this tweet:

Hey everybody, Al Qaeda is using this hashtag to solicit ideas for media ops #اقتراحك_لتطوير_اﻹعلام_الجهادي — you should all send some.

— J.M. Berger (@intelwire) August 13, 2013

Leading inevitably to:

https://twitter.com/spankthemoney/status/367612117391654913

https://twitter.com/TomKenniston/status/367706613290790912

And the Dish fave:

1) Use a false interpretation of an old text to justify killing innocent people. 2) ???? 3) PROPHET! ! #اقتراحك_لتطوير_اﻹعلام_الجهادي

— Marc Solomon (@magicbravosolo) August 14, 2013

Robo-Nannies?

They may be on the horizon:

People today may believe that it would be inhuman or immoral to leave young children at

home alone with a robot or to drop them off at a day care center staffed by machines. But economic and technological changes of the past have already transformed child-rearing attitudes and practices: take test tube babies, working mothers, screen time, fast food or children with their own telephones.

There is little need to worry that machines will take over all aspects of child rearing. People will always have a comparative advantage over machines, even if machines could in principle be better at just about anything. For the same economic reason that the world can produce more by assigning some tasks to unskilled people and other tasks to talented people, people will be doing tasks that are difficult for machines relative to other tasks.

But perhaps robots will make parenting easier and thus more popular.

More Dish on the potential for robotic friends around the house here.

(Image of Tinker the Robot from Cybernetic Zoo)

The Case Against The Personal Essay

Phoebe Maltz Bovy argues that “only fiction can be about the trivial without being trivial”:

The miracle of fiction is less about its execution than its promise: a story, not a delivery of life advice or an exhaustive documentation of reality. While personal essays fail as news because the subject matter isn’t newsworthy, they fail as storytelling because of how the texts are classified. A first-person protagonist and author may share a name and every event described may have happened as recorded, but if the document is labeled nonfiction, we respond to it differently.

Imagine Lucky Jim presented not as a novel but as a personal essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education. We’d be chastising the writer for his poor work ethic and for not being appropriately appreciative of his good fortune to even have a job. Or compare Jami Attenberg’s recent novel, The Middlesteins, about an obese matriarch, with the New York Times’s health-blog series “Fat Dad.” Take a wild guess at which of the two inspired the following response: “Thank you for this very important piece about the importance of family meals.”

No matter how rich the storytelling, the online personal-essay format, with its subtlety-free headlines and comments-welcome presentation, reduces these texts from nuanced portraits of human behavior to straightforward arguments about how to live.

America’s Semen Reserves

Jesse Hirsch reports from the USDA’s strategic livestock-semen reserve in Colorado, which holds about 700,000 frozen samples from cattle, bison, goats, pigs, elk, and other animals:

Every straw has a story. There are 30,000 salmon milt samples, obtained from the Nez Perce tribe in Idaho. There’s rare sheep semen from Kazakhstan, near sheep’s center of domestication. There’s even a full backup of 20,000 exclusively bred cows on the Island of Jersey, progenitors for Jersey cattle all over the globe.

So where does it all come from? Universities, companies and private collectors often donate semen to the NAGP. Other samples are tracked down by Blackburn and his colleagues. One woman in Broken Bow, Nebraska, had a rare breed of cattle dating back to the 1940s. “We called this farmer, asking for semen from her bulls,” Blackburn says. “She picked up the phone and said, ‘I thought you’d never call.’”

The archive includes “rare and vintage” seed, but don’t accuse the USDA of snobbery: Hirsch reports that “everyday strains are just as important as the heirloom semen, if not more so.”

(Photo of frozen bovine sperm via Wikicommons)

Correcting Franzen

Jonathan Franzen’s recent interview with Colombian author Juan Gabriel Vásquez aggravates Chad W. Post’s anti-Franzen bias. He cites the following question as evidence:

Jonathan Franzen: I’m struck by how different in feel The Informers and The Sound of Things Falling are from the Latin American “boom” novels of a generation ago. I’m thinking of both their cosmopolitanism (European story elements in the first book, an American main character in the new one) and their situation in a modern urban Bogotá. To me it feels as if there’s been a kind of awakening in Latin American fiction, a clearing of the magical mists, and I’m wondering to what extent you see your work as a reaction to that of Márquez and his peers. Did you come to fiction writing with a conscious program?

“This is the kind of bullshit question that no one would ever ask an American author,” says Post, who rewrites the above passage:

I’m struck by how different in feel The Corrections and Freedom are from the American “modernist” novels of a generation ago.

I’m thinking of both their disinterest in language and representations of the inner workings of the human experience (the straightforward neo-realistic prose that dominates both of them) and the obsession with the suburbs. To me it feels as if there’s been a kind of awakening in American fiction, a clearing of the obfuscating mists, and I’m working to what extent you see your work as a reaction to that of Faulkner and his peers. Did you come to fiction writing with a conscious program?

Post’s point:

Implicit in Franzen’s question is the idea that there was—or is—a certain “type” of Latin American writing and that anything different than that is some sort of political statement or bold move, as if Latin American writers can’t write about Europe or America or anything modern and universal. Get back to the banana plantations and bring us some talking butterflies! Beyond being insulting to Latin American writers, it really makes the person asking the question—Franzen in this case—seem like an ignoramus. So all y’all Mexicans actually know about Europe? Holeey shit!

Meanwhile, Jason Diamond assembles “A Handy Guide To Why Jonathan Franzen Pisses You Off” here.