Marking the 20th anniversary of the genocide, Lauren Wolfe considers how far the country has come and how it still struggles to cope with its past:

Today, 20 years after an ethnically motivated genocide in which nearly 1 million Rwandans died and up to half a million women were raped, the government forbids certain kinds of public discussion about Hutus and Tutsis. When I visited the country in February, I heard a lot of chatter about something called “Vision 2020,” which is supposed to transform the country into a thriving state marked by good governance and a healthy economy. Construction is booming in the capital, Kigali, and President Paul Kagame has expressed a desire to make his country more like Singapore—a sort of authoritarian democracy. There is a robust effort, in other words, to deliberately “move on” from the tragedy—a determination to never lose control again.

Katy Migiro examines how the memory of the genocide is politicized:

Some argue that the government, led by Kagame, a Tutsi, constantly evokes the horrors of the genocide to justify its tight grip on power. Last year, it launched a campaign called “I am Rwandan,” which has seen Hutus born after the genocide apologize in the name of their ethnic group.

“[Kagame] wants the blood to keep flowing symbolically,” said Gérard Prunier, a French academic who has moved from being a Kagame sympathizer to a fierce opponent. “He wants the survivors to be full of hatred and pain because that’s the basis of his legitimacy.”

The one-sided nature of the government’s genocide narrative is making it difficult for many to bury the past, analysts say. There is no official recognition of Hutu who were killed either during the genocide or in revenge massacres by the RPF, in which up to 30,000 Hutu died, according to a leaked United Nations report.

James Hamblin praises the country’s progress in improving public health since the genocide:

Rwanda was left with the world’s highest child mortality and lowest life expectancy at birth. Fewer than one in four children were vaccinated against measles and polio. … Few imagined that Rwanda, a country the size of Maryland, would so soon—if ever—serve as an international model for health equity.

Just two decades later, that life expectancy has doubled. Vaccination rates for many diseases are now higher than those registered in the United States—more than 97 percent of Rwandan infants are immunized against ten different diseases. Child mortality has fallen by more than two thirds since 2000. New HIV infection rates fell by 60 percent between 2000 and 2012, and AIDS-related mortality fell by 82 percent. HIV treatment is free.

But Marie Berry argues that Rwanda’s rapid development has not benefited everyone:

Outside of the modern Kigali neighborhoods and beneath the country’s orderly surface, things look quite different. Armed security officers stationed at regular intervals around Kigali ensure the city is secure, but also reflect the repression needed to maintain this security — a repression with other dimensions, found in tight (and at times bizarre) regulations on people’s everyday lives. Groups of young men stand idle in front of storefronts, seemingly socializing but really just killing time — they have no work to do. In crowded markets or bus stations, these unemployed youth beg desperately for jobs.

As for Rwanda’s women, many of them sell fruit and vegetables from baskets by the side of the road, but their work is illegal, and they flee at the first sign of police. Others line the dimly lit streets at night in Kigali’s seedier neighborhoods, selling sex — sometimes for next to nothing — to keep their children fed and their rent paid.

On the other hand, Swanee Hunt shows how the country has made great strides in gender equality:

Half of the country’s 14 Supreme Court justices are women. Boys and girls now attend compulsory primary and secondary school in equal numbers. New, far-reaching laws enable women to own and inherit property and to pass citizenship to their children. Women are now permitted to use their husbands’ assets as collateral for loans, and government-backed funds aimed at encouraging entrepreneurship offer help to women without familial resources. Established businesswomen are leading members of Rwanda’s private-sector elite. And the advance of women in the political sphere has received global attention. In 2000, the country ranked 37th in the world for women’s representation in an elected lower house of parliament. Today, it ranks first.

Meanwhile, J.J. Carney notes that spillover from the genocide continues to affect the region:

Not only did Rwanda suffer more massacres (some directed at Hutu) between 1995 and 1998, but Burundi’s civil war continued until 2006. Perhaps worst of all, Eastern Congo after 1996 became the epicenter of what many scholars have dubbed “Africa’s World War.” The precipitous cause of the conflict was Rwanda’s invasion of Congo in October 1996, ostensibly to clear Hutu refugee camps that were serving as staging grounds for cross-border raids into Rwanda. Upwards of four million Congolese died from war-related causes over the next six years. Over a decade later, Rwandan-backed militias continue to dominate Congo’s Kivu provinces. The “afterlife” of the Rwanda genocide thus continues even in 2014.

James Traub worries that a more risk-averse United States is less likely to step in and prevent or stop tragedies like the 1994 genocide:

What, then, is the legacy of Rwanda? First, that reconciliation is possible even after the most horrific violence. Second, that the world has now developed mechanisms, and diplomatic reflexes, that may be deployed to prevent violence from exploding into mass killing. Regional organizations like the African Union are now prepared in some cases to send troops to quell such violence.

But when the killing can be curbed only by the kind of force the West can bring to bear, the world will look to the United States, which means, to the president. And a sad legacy of Rwanda that we witness now in Washington is a president that looks at his options much more skeptically than advocates of action, including those in the White House — both because he is fully aware of the kinks and weak spots of every plan, and because he fears the costs of failure. He will act only when the probability of success is very high.

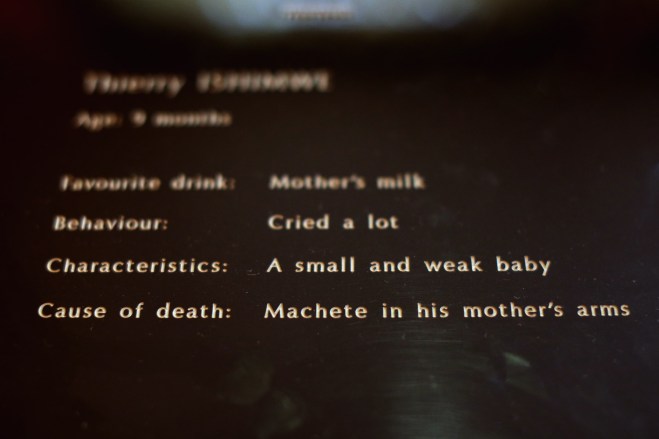

(Photo: The fate of 9-month-old genocide victim Thierry Ishiwme is displayed at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali, Rwanda on April 5, 2014. Rwanda is commemorating the 20th anniversary of the country’s 1994 genocide, when more than 800,000 ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutus were slaughtered over a 100 day period. By Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)