In light of yesterday’s ruling in Harris v. Quinn, which limited the ability of public sector unions to collect dues from non-members, Philip Bump explores the shifting landscape of organized labor in America:

The decline in union membership is itself in part due to politics. In 2012, Michigan and Indiana passed “right to work” laws backed by conservative groups that allow workers to benefit from union-negotiated contracts without having to make any contribution to the union. That’s the issue at the heart of Harris. And there’s a reason groups opposed to unionization focus on it: Ending the practice would grievously harm public sector unions.

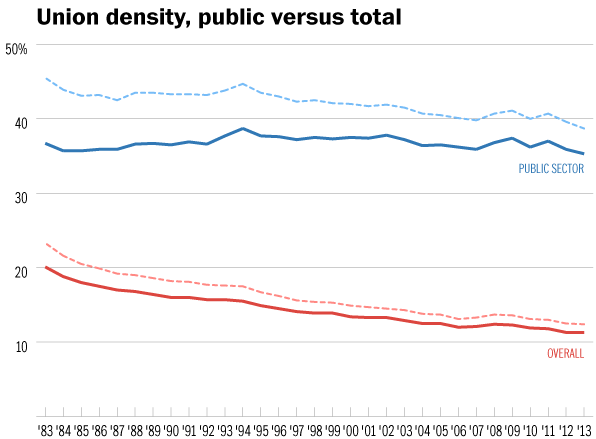

Public sector unions have been a bright spot in the labor movement. The graph [seen above] shows how membership has plummeted overall, but held steady in public sector employment. The dashed lines, incidentally, shows those employees covered under a union contract but who are not union members.

Jake Rosenfeld pushes back against the fears of the pro-labor left – and the hopes of anti-labor right- that “right-to-work” laws will deal a death blow to unions:

Despite all the heated rhetoric on both sides of the union divide, there isn’t much evidence that “right-to-work” laws actually reduce union representation. Consider the following:

- In the United States, according to research by the economist William Moore, the vast majority of workers covered by collective bargaining contracts in “right-to-work” states pay union dues. Freeriding is rare. Many workers likely feel guilty for receiving benefits for free—and their union-contributing co-workers serve as constant reminders that they are benefitting from others’ labor.

- In recent years, the success of unions in Las Vegas—most notably the Culinary Workers Local 226—has been a real bright spot for organized labor in the United States. Las Vegas, of course, is in Nevada, a “right-to-work” state. (Other “right-to-work” states have quite low unionization rates, but their rates were already low prior to passing “right-to-work” legislation.)

- Across other industrialized nations, research finds that “closed-shop” provisions that compel the paying of union dues in unionized workplaces have little correlation with union strength.

And Andrew Grossman comments that the law at issue in Harris was part of an effort to bring home care workers into the Service Employees International Union, more for the union’s sake than for the workers’:

Though a recent phenomenon, the use of sham employment relationships to support mandatory union representation has spread rapidly across the nation. In just the decade since SEIU waged a “massive campaign to pressure [] policymakers” in Los Angeles to authorize union bargaining for homecare workers, home-based care workers “have become the darlings of the labor movement” and “helped to reinvigorate organized labor.” From around zero a decade ago, now several hundred thousand home workers are covered by collective-bargaining agreements.

This quick growth is the result of a concerted campaign by national unions, particularly SEIU, to boost sagging labor-union membership through the organization of individuals who provide home-based services to Medicaid recipients.