https://twitter.com/marieharf/status/497729146358099968

https://twitter.com/PentagonPresSec/status/497725099970031616

For Lawrence Kaplan, Obama’s decision to authorize airstrikes on ISIS targets in Iraq was a no-brainer:

The Yazidi, a tiny sect probably as old as the biblical province its members call home, have nearly been wiped out on dozens of occasions, by dozens of persecutors, and yet they survive. During the Iraq War, they turned to the Americans for protection, and the Americans turned to them for all manner of support. (The Yazidi supplied a disproportionate number of interpreters to the U.S. Army.) For this, the insurgents slaughtered the Yazidi, killing 500 on a single day in 2007. Whenever I would visit their ancestral home in the town of Sinjar, they would plead for stepped-up assistance from Washington.

The Yazidi need that assistance, and they need it today. For an administration that famously prefers to achieve its desired results abroad through suasion rather than brute force, this presents a conundrum. It should not.

Christine Allison argues that protecting Iraq’s religious minorities is a moral obligation:

If, through our own inactivity, we allow the Yazidis and Christians to suffer so much that they leave the country, what are we doing to Iraq, the cradle of civilisations? What about the smaller minorities, Shabaks and Mandaeans, who have found stability and shelter in the Kurdish region? Do we sit back and watch an extinction event in northern Iraq? As we commemorate the centenary of the first world war, we have only to look over Iraq’s border to see Turkey’s struggle to come to terms with its past in those years. Inaction in Iraq now will produce the same result: an ethnically “cleansed” landscape, a haunted population.

So now, in addition to our humanitarian efforts, we must turn to the Kurds, who, with their referendum on independence are apt to be perceived as causing “the break-up of Iraq”. But paradoxically, with their forces on the ground, they are the best protectors of northern Iraq’s diverse population. Air strikes and humanitarian drops are a beginning. But in the medium and longer term, London and Washington must find a way to maintain the balance of power between Baghdad and Kurdistan and still work closely with Kurdistan’s fighting forces to assure security.

Dreher also throws his full support behind the intervention:

It is my devout hope that the US kills as many ISIS berserkers as we possible can. I saw today video of a Christian child who had been decapitated by these monsters, and heads of Christians on pikes. There was news today that they were slaughtering Yazidi men and taking their wives as plunder. They are worse than Waffen SS. I’m pretty strongly noninterventionist, but that is not an absolute position, especially not when we can fairly be blamed for setting off this crisis. As they say in Texas, some people just need killin’.

Morrissey calls Obama’s announcement “the right and … only possible steps”, though he doubts airstrikes alone will do the job:

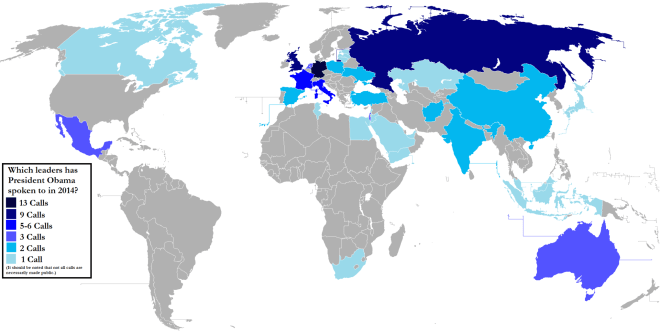

The Kurds have spent the last 23 years living in peace and freedom, relying on the US to protect their interests while being caught between the Turks, Iranians, and Iraqis. Walking away from the Kurds after their long support of our efforts to stabilize Iraq even at the expense of their own dreams of independence would be a betrayal that would send shock waves around the world to other groups working with the US — especially in Afghanistan. The Kurds will be the canary in the coal mine of American credibility for decades to come.

In the meantime, it will take more than a couple of airstrikes to stop the genocides of ISIS to come. The so-called Islamic State and its leadership is perhaps the most explicitly bloodthirsty regime to arise in generations or perhaps centuries, and nothing short of utter defeat will stop them from continuing to annihilate all those who do not bow down to them. The US and the West will have come to grips with this reality sooner or later, and in terms of lives lost and the effort necessary to stop ISIS, sooner would be much more preferable.

To Dan Hogdes, the events in Iraq prove that the US has to be the world’s policeman:

When people say “We don’t want America to be the world’s policeman,” I don’t think most of them actually mean it. What they really mean is “We don’t want America to be the world’s policeman, and the world’s prosecutor, judge and jury as well.”

And that’s a fair argument. But at the moment, with the implosion of the authority of the UN, there is no effective prosecutor, judge or jury. Earlier this week the UN patted itself on the back for the successful conviction of Khmer Rouge leaders Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan. They are 88 and 83 respectively. Their victims – an estimated two million of them – died 40 years before. Pol Pot himself never faced justice. If we want a world based on laws then someone ultimately has to enforce them. And there is only one state on the planet with the means and inclination to do so. That state is the United States.

But the limits of the mission are very much in doubt. Ryan Goodman questions them:

[I]s this mission really just to protect US personnel or also to aid the Kurds? The New York Times reported that “aides said [the President’s] hand was not forced until ISIS won a series of swift and stunning victories last weekend and Wednesday night against the Kurds in the north, who have been a loyal and reliable American ally.” Similarly, Rep. Adam Smith, the ranking Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee, said “he supported intervening on behalf of the Kurds, as opposed to the unpopular Baghdad government. ‘The Kurds are worth helping and defending.’”

On the second mission (protecting religious minorities on Mount Sinjar), the President outlined three criteria for such humanitarian actions: “[1] innocent people facing the prospect of violence on a horrific scale, [2] when we have a mandate to help — in this case, a request from the Iraqi government — and [3] when we have the unique capabilities to help avert a massacre.” It is unclear, in my mind, why those three criteria won’t also apply to ISIS’s genocidal efforts elsewhere in the country, and the US ability “to help avert” those massacres.

Zack Beauchamp believes that the “key cause of all of this is ISIS’ somewhat surprising advance into territory held by Iraq’s Kurds”:

“This is a big deal,” Phillip Smyth, a researcher at the University of Maryland who follows this situation closely, said. “First, they push the Christians out of Mosul [Iraq’s second-largest city], and now they’re doing that.”

Smyth sees at least two basic motivations for the ISIS advance. One is simple opportunism: not every Kurdish unit is equally strong, and ISIS will take any territory it thinks it can, given the chance. The second is more strategy: they likely want to cut off Iraq’s Kurds from Kurdish communities in Syria, where ISIS is fighting a second front against the Syrian government. “They’re trying to cut off geographic links between those two territories,” he said.

John Cassidy asks, “Once the U.S. bombing starts, when will it stop?”:

That is one of the many tough questions that Obama and his colleagues will have to answer. Are the sole goals of the mission to help out the Yazidis and prevent Erbil from falling? Or is this the beginning of a U.S.-led effort not merely to halt the advance of ISIS on its eastern front, in the Kurdish region, but to roll it back everywhere in the country? On these questions, Obama was studiously ambiguous. … Already, though, one Rubicon has been crossed. A President who came into office on a promise to pull the United States out of Iraq, and who followed through on his pledge, has just ordered more combat operations in, or over, Iraq.

Josh Marshall wants to know what changed on the ground to tip Obama towards intervention, and why our understanding of ISIS’s and the peshmerga’s capabilities has been so wrong:

[W]hat’s happened to ISIS, which was supposed to be a fairly small, rag tag force, highly spirited perhaps but not a force capable of making gains against a disciplined regular army? Quite a bit of American weaponry did fall into ISIS hands when the Iraqi Army fled. But advanced weaponry usually requires significant training to use effectively or at all and additional time to integrate its use into a fighting force. It seems highly questionable that all that weaponry could have transformed ISIS’s capabilities so quickly.

And if ISIS hasn’t changed, is it possible that the Peshmerga were never really the vaunted force they were made out to be? That’s the question asked by this editorial in a Saudi paper. Whether it’s one of these misapprehensions or the other or both, either would seriously change the situation in Iraq from what we’d been led to believe as recently as a few days ago.

Indeed, if the Kurds can’t finish ISIS on the ground, even with American air support, what happens then? That’s where Jacob Siegel spots a major flaw in Obama’s plan:

The consensus among ex-CIA analysts, former military officers, and Iraq veterans who spoke with The Daily Beast is that the Peshmerga’s abilities were overrated. No one questions the Kurds’ willingness to fight, but their military prowess appears to have degraded in the years since the U.S. military stopped training them and withdrew from Iraq. … Air strikes against ISIS targets can weaken the group, buy time, and prevent it from massing on Kurdish forces, but according to military and CIA veterans, air power alone will not be decisive.

“The advisors need to be pushed out, if they haven’t been already,” said Nada Bakos, a CIA veteran who led the team analyzing the terrorist network that was ISIS’s predecessor in Iraq. The advisors she referred to are the special operations troops who have so far stayed away from the battlefield, offering intelligence and advice from headquarters in areas remote from the fighting.

Juan Cole is having flashbacks to 1991:

The Neocons who wanted to go to war against Iraq in the early zeroes always said that one reason a war would be good was that the US was spending a lot of money on the no-fly zone over Kurdistan– as if a whole war wouldn’t be much more expensive (it was, by about $1 trillion). Apparently not only has the Iraqi federal army almost completely collapsed, finding itself unable to take back Tikrit, but now the so-called Islamic State was making a move on Iraqi Kurdistan’s capital of Irbil. Obama’s hope that the so-called “Islamic State” can be stopped by US air power is likely forlorn. The IS is a guerrilla force, not a conventional army. But one thing is certain. A US-policed no fly zone or no go zone over Iraqi Kurdistan is a commitment that cannot easily be withdrawn and could last decades, embroiling the US in further conflict.

Lastly, Michael Crowley remarks on Obama’s evolution when it comes to genocide and US intervention:

In his 2007 comments about genocide, Obama at least seemed to imply that, because the U.S. can’t prevent slaughter everywhere, it shouldn’t take humanitarian action anywhere. But as President he has adopted a different point, first in Libya and now in Iraq: Just because we intervene in some places doesn’t mean we have to intervene everywhere. That doesn’t make for a very tidy doctrine. Nor will it console the miserable people of Syria. But it will bring jubilation to the terrified thousands on Mount Sinjar, for whom salvation is now coming.