Sullybait: data from the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System now proves that New Yorkers are the unhappiest residents of a metro area in America. No: seriously. Huge numbers of people answer the CDC question, “In general, how satisfied are you with your life?” with four options: satisfied, very satisfied, unsatisfied, very unsatisfied. From the results of that, a new study controlled for things like wealth, age, race, education etc. and came to the staggering conclusion that the inhabitants of the Greatest City On The Planet are fucking miserable. Slate‘s Jordan Weissman was skeptical – I mean who wouldn’t be thrilled to live in that magnificent metropolis?

So I decided to check out the research team’s full data set, without all the fancy adjustments. Turns out, New York still takes the grand prize for big-city misery. Based on its raw happiness scores, the metro area was the third unhappiest overall, finishing just above Jersey City, New Jersey (which is basically an extension of Manhattan’s financial district), and ever-woeful Gary, Indiana. Among city regions with a population of at least 1 million, New York came in last. The same pattern held if you adjusted the data for demographic characteristics but not income. Any way you look at the numbers, the New York state of mind appears to be one of personal dissatisfaction.

NYC emerges at #56 in the happiness survey of cities. Washington DC? #5. Just sayin’.

Today, I detailed the rise and rise of eliminationist rhetoric in Israel. For a review of the definitional eliminationism of Hamas, go read Jeffrey Goldberg. Wars are like poultices: they bring all sorts of toxins to the surface.

I also worried about Obama’s possible executive action on illegal immigration; I noted that the GOP cannot muster enough votes for a resolution congratulating the Pope; Rich Juzwiak and I talked about sex without condoms, i.e. the activity formerly known as sex for almost all human history; readers came to the defense of Hillary Clinton’s vacuousness; and if you love beagles, you’ll love this video.

Speaking of beagles, it was a year ago today that we had to put Dusty down. She’s the model for the dog at the top of the page, and a constant presence in my life for fifteen and a half years. Her ashes still sit on the shelf here in Ptown, but the cottage is full of the energy and love of a puppy called Bowie. She shoves the pain instantly away. But every now and again I think of Dusty. And wonder where she is.

The most popular post of the day was The Last And First Temptation Of Israel; followed by Why Sam Harris Won’t Criticize Israel.

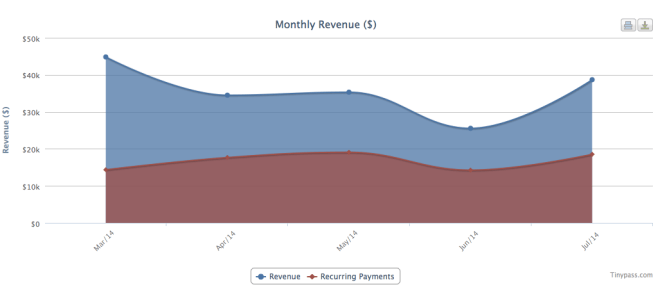

Many of today’s posts were updated with your emails – read them all here. You can always leave your unfiltered comments at our Facebook page and @sullydish. 21 more readers became subscribers today. You can join them here – and get access to all the readons and Deep Dish – for a little as $1.99 month. Gift subscriptions are available here. Dish t-shirts and polos are for sale here – and our premium tri-blend shirts are selling out soon, so don’t delay.

See you in the morning.

(Photo: Stone crosses marking the graves of German soldiers are overtaken by time and and the growing trunk of a tree in Hooglede German Military Cemetery on the centenary of the Great War on August 4, 2014 in Hooglede, Belgium. Yesterday marked the 100th anniversary of Great Britain declaring war on Germany. In 1914 British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith announced at 11 pm that Britain was to enter the war after Germany had violated Belgium neutrality. The First World War or the Great War lasted until 11 November 1918 and is recognised as one of the deadliest historical conflicts with millions of causalities. By Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)