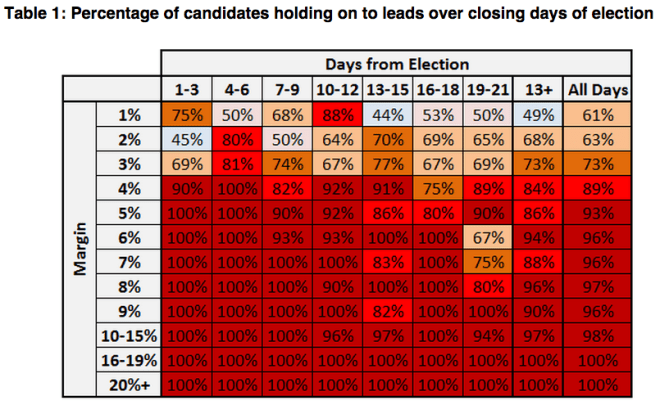

Sean Trende created the above table to answer a question: “At any given number of days out, if a candidate has a lead of a certain size, how often does that candidate win?”:

An example of how we would read this chart with respect to current polls: Assume that as we get polls from the North Carolina race that concluded Tuesday, Wednesday, or today, they confirm Sen. Kay Hagan’s (D) lead of roughly two points. Candidates who lead by two points 19-21 days out win about 65% of the time. So we’d conclude that Hagan is the favorite, but her lead is not insurmountable.

Like other poll watchers, he calculates that Republicans are favored to take the Senate:

To predict Democrats retaining Senate control, you basically have to bet on (a) Democrats sweeping South Dakota, Iowa, Colorado, and North Carolina; (b) picking off enough Republican seats in very red states like Kentucky, Kansas, or Georgia to offset any losses in (a) or; (c) systemic polling failure. You can make a plausible case for each of those scenarios, with (b) probably being the most likely. Regardless, given the current state of polling and knowing how races have behaved over the past few cycles, those really do appear to be the options left for Democrats.

However, the 538 forecast only gives Republicans a 60.1 percent chance of winning the upper house. Harry Enten explains:

How is that possible, even as some other models have seen Republican chances climb higher and higher? The FiveThirtyEight model is relatively conservative: It takes more evidence to convince the model a race has shifted and more evidence to convince it a state is totally out of play.

The model views a larger group of states as competitive compared to other forecasts. So movement in the more marginal battleground states — the Democrat solidifying his lead in Michigan, or the Republican pulling away in Kentucky, for example — matters more. If you consider those states as mostly out of play, the favorites improving their position there won’t affect your overall outlook as much.

Sam Wang speculates about the polls being off:

If every front-runner today were to win, the Senate outcome would be 52 Republicans and 48 Democrats and independents. But history tells us to expect two or three of the current leaders to lose. Democratic wins in the key states of Iowa and Colorado would give a 50-50 split, with Vice President Joe Biden breaking Senate ties in his party’s favor. (This assumes that Kansas independent Greg Orman would caucus with Democrats and the other independents, which is not a sure bet.) Of course, if the opposite were to happen North Carolina—with Republican Thom Tillis defeating Democratic Senator Kay Hagan, who leads narrowly—the GOP would end up with a convincing 53-47 majority.

Regardless, Americans aren’t paying much attention to the midterms. And Dylan Matthews observes that, “according to a Wall Street Journal/NBC poll, Americans are actually losing interest as the race progresses.”