Warren, Vermont, 10.14 am. “We’ve just received 2.5 feet of super-heavy, wet snow!”

Month: December 2014

Quote For The Day

“[T]he adorable little weenie I knew from our days at The Daily Penn-sylvanian was nothing but a con artist. … No one on TNR’s staff is suspicious of the painfully self-deprecating kid who is so eager to please. [Actor Hayden] Christensen plays [Stephen] Glass as more obsequious than the real-life version, but conveys the original’s disarming charm. He comes across as utterly harmless; even his sexless demeanor seems designed to avoid offense. His friends can’t help but want to protect him. Which helps explain why Glass’s deceptions aren’t caught sooner; his peers simply want to believe him too badly,” – Sabrina Rubin Erdely, Rolling Stone writer, in 2004.

Hanna Rosin has a must-read on the latest gobsmacking revelations from the UVA story.

(Hat tip: Eric Owens)

Silence, Audible, Ctd

Chris Christie opposed torture in 2002:

But, thus far, he has declined to weigh in on the Senate report:

Asked for his reaction by The New York Times, Mr. Christie said, “All I’ve seen, unfortunately, at this point, is some of the reporting from your newspaper, so I don’t think it would be responsible to comment based only on that.” He said of the report: “I’ll take some time to look at it. I don’t know about all of it. But I’ll take some time to get briefed on it for sure.”

Noah Rothman wants him to get off the sidelines:

If Christie believed that the Senate Intelligence Committee’s investigation was not as thorough as it needed to be in order to come to the politically fraught conclusions it reached, it would have been advantageous for him to say as much. Considering the number of sources making this same contention, Christie would not have been in bad company. If, however, Christie is predisposed to agree with the findings of the SSCI’s report, he should have made the time to be briefed on its conclusions within the first 24 hours of its release.

It’s still possible. The Clintons, meanwhile, say nothing in one of the most significant moments in America’s moral and constitutional history. Neither does Jeb Bush. Why am I not surprised? Update from a reader:

What has Pope Francis to say, I wonder?

What Did Bush Know And When Did He Know It?

For me, the question remains a fascinating one. The revelation that the first briefing that Bush got on waterboarding was in 2006 is a staggering finding. His own book contradicts this. But the CIA has no records of briefings other than that. And their internal response to his 2006 speech showed how distant they were. When he indicated that no inhumane practices were being used, the CIA wondered if their program had been suspended without their knowledge!

But Fred Kaplan doesn’t buy the claim that Bush didn’t know what was going on:

[L]et’s take a close look at the committee’s claim that Bush wasn’t briefed on the program until it had nearly run its course: “According to CIA records,” the report states, “no CIA officer, up to and including CIA Directors George Tenet and Porter Goss, briefed the president on the specific CIA enhanced interrogation techniques before April 2006.”

I’ve italicized two words in this passage, for emphasis. The second word is key: Bush wasn’t briefed on the “specific” techniques till 2006. Under the well-known rules of plausible deniability, he would not have wanted to know too much about these specifics. As indicated in the station chief’s presentation, it’s not that the CIA didn’t tell the president certain details; it’s that the president didn’t want the CIA to tell him.

I think that’s easily the best explanation. Bush was briefed the way we all were about “enhanced interrogation” in language designed to obscure the reality. “Long-time-standing,” for example, sounds relatively mild. It does not fully convey the fact that prisoners with broken legs and feet were put in stress positions – the kind of torture you’d expect from ISIS. But there was surely also a desire not to know, not to have direct and explicit knowledge of what was actually being done, because of the immense gravity of the crimes. Who protected him? Almost certainly Alberto Gonzales. Maybe Condi.

Here’s my best guess after puzzling about this for a decade. Bush made the fateful decision to waive core Geneva protections from prisoners suspected of terrorism early on. That was his signal. He told everyone in the CIA (and beyond) in a moment of extreme emotion that you could do anything to these prisoners you wanted. In that sense, Bush is completely and personally responsible for every act of torture on his watch. He is as responsible as the men who decided to waterboard a prisoner until hardened operatives choked up and walked away.

But he then disappears in the CIA records – and Obama refused to give the Senate Committee the White House records that could have cleared it up (another instance of Obama covering up evidence of war crimes). Cheney presumably handles it all – with Addington doing clean-up – giving Bush the reassurances that a) the torture was giving up vital information saving lives (a lie) and b) that it was all legal (only by making an ass of the law in memos that were subsequently rebuked and rescinded). I suspect that this was all Bush decided he wanted to know: it works and it’s legal. And the famously incurious president didn’t want to know any more. I remember in 2005 asking a very senior administration official if we were torturing prisoners. The carefully parsed response, after looking down and away from me: “The president doesn’t believe we’re torturing people.” They were crafting a way to insulate him from war crimes done in his name.

Serwer likewise finds it “hard to believe that the Bush administration couldn’t have had any clue about what was really going on at the CIA”:

Less than a week after the 9/11 attacks, Bush signed an order allowing the CIA to detain and interrogate terror suspects, and in February 2002, he signed “a memorandum stating that the Third Geneva Convention did not apply to the conflict with al Qaeda and concluding that Taliban detainees were not entitled to prisoner of war status or the legal protections afforded by the Third Geneva Convention,” according to a 2008 Senate Armed Services’ Committee investigation.

So: Mere months after the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration was already rewriting the law to make it easy to torture detainees in U.S. custody. You don’t start declaring exceptions to the Geneva Convention if all you’re planning to do is play a competitive game of spades.

The CIA is not “a rogue elephant,” in the deathless phrase of Senator Frank Church, who ran the pioneering congressional investigation of the agency four decades ago. If the beast tramples people, it’s the mahout, the elephant driver, who is to blame. There was clearly one person driving this program, whether he knew what the elephant was doing in his name or not.

The mahout in the Senate report is the president of the United States.

And he stands accused of war crimes in front of the whole world.

Cheney Is Lying

In his deeply revealing interview on Fox News last night, former vice-president Dick Cheney was asked which plots were foiled using torture, thereby saving thousands of lives. The first and only case he cited last night was the “West Coast” “Second Wave” plot against buildings in Los Angeles. He’s cited this many times before. And here’s the thing: It’s a lie. It’s not true. And we now know it’s not true, because the CIA itself admitted it last year, after a decade of lying about it.

Cheney hasn’t read the report, although he knows it’s “full of crap.” What that tells you about this man’s integrity and honesty I’ll leave to you. But here is what he hasn’t read.

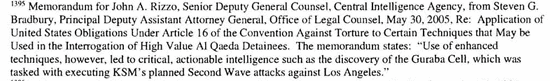

The CIA, from the beginning, cited this case as a critical piece of evidence for the efficacy of torture, in all its briefings to officials. To take one random example, here is a legal memo from Steven Bradbury, at the OLC, conveying what the CIA was telling him:

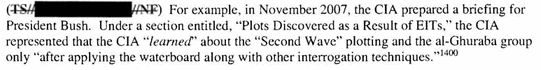

So torture gave us the existence of the Guraba cell, which foiled the plot. The CIA told Bush the exact same thing:

So torture gave us the existence of the Guraba cell, which foiled the plot. The CIA told Bush the exact same thing:

This was a lie. How do we know? Because CIA operational cables and internal documents tell a different story. The FBI arrested two operatives in August 2001, including a “suspected airline suicide attacker” and that provided the leads for further identification of al Qaeda operatives involved in the Gubara version of the attack. Another plot on similar lines by some Malaysian nationals, coordinated by KSM, was foiled when one Misran bin Arshad was arrested in January 2002, revealing, by the way, that the attack had already been canceled the month before. Arshad spilled the beans after legal and non-coercive interrogations. So, according to the CIA, torturing KSM gave us nothing that we didn’t already have; and agents deduced that what intelligence they did get from KSM about this was because he knew that Arshad had already been captured – not because he had been tortured.

This was a lie. How do we know? Because CIA operational cables and internal documents tell a different story. The FBI arrested two operatives in August 2001, including a “suspected airline suicide attacker” and that provided the leads for further identification of al Qaeda operatives involved in the Gubara version of the attack. Another plot on similar lines by some Malaysian nationals, coordinated by KSM, was foiled when one Misran bin Arshad was arrested in January 2002, revealing, by the way, that the attack had already been canceled the month before. Arshad spilled the beans after legal and non-coercive interrogations. So, according to the CIA, torturing KSM gave us nothing that we didn’t already have; and agents deduced that what intelligence they did get from KSM about this was because he knew that Arshad had already been captured – not because he had been tortured.

And the CIA admitted as much last year:

The CIA’s June 2013 Response acknowledges that “[t]he Study correctly points out that we erred when we represented that we ‘learned’ of the Second Wave plotting from KSM and ‘learned’ of the operational cell comprised of students from Hambali.” Here’s the full section:

But notice that they cannot quite admit what they have admitted. They accept that they misled the president, but called it “imprecision,” rather than untruth. Then they bizarrely continued to “assess this was a good example of the importance of intelligence derived from the detainee [torture] program.” Then they threw in another claim – that the capture of another figure, Hambali, had been critical to foiling the plot as well, and that his capture was a function of the torture program. But the CIA’s own documents show that Hambali’s capture was unrelated to to the program. After a while, when you read this report closely, you cannot avoid seeing that they’re flailing around. They’ve got nothing but bluster and bluff. And when you watch the amazing Cheney interview, you realize he has nothing else either. All he has is bluff. But what he said last night was wrong. The CIA itself has said it was untrue.

But notice that they cannot quite admit what they have admitted. They accept that they misled the president, but called it “imprecision,” rather than untruth. Then they bizarrely continued to “assess this was a good example of the importance of intelligence derived from the detainee [torture] program.” Then they threw in another claim – that the capture of another figure, Hambali, had been critical to foiling the plot as well, and that his capture was a function of the torture program. But the CIA’s own documents show that Hambali’s capture was unrelated to to the program. After a while, when you read this report closely, you cannot avoid seeing that they’re flailing around. They’ve got nothing but bluster and bluff. And when you watch the amazing Cheney interview, you realize he has nothing else either. All he has is bluff. But what he said last night was wrong. The CIA itself has said it was untrue.

We have a former vice-president going on cable news and continuing to say things in defense of the CIA that the CIA itself admits are untrue. This is his p.r. strategy: asking the American people who they are going to believe: Dick Cheney or their own lyin’ eyes? More on the Cheney interview to come.

Team Torture

Look, quit navel gazing on this CIA torture report. Yea we engage in torture. Good. Big deal. Now go focus on defeating the Islamic enemy.

— Joe Walsh (@WalshFreedom) December 9, 2014

This cretin was in the US Congress https://t.co/CoaIBNS8Zt

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) December 9, 2014

Noah Millman believes that our reasons for torturing weren’t based on torture’s effectiveness:

Willingness to torture became, first within elite government and opinion-making circles, then in the culture generally, and finally as a partisan GOP talking point, a litmus test of seriousness with respect to the fight against terrorism. That – proving one’s seriousness in the fight – was its primary purpose from the beginning, in my view.

It was only secondarily about extracting intelligence. It certainly wasn’t about instilling fear or extracting false confessions – these would not have served American purposes. It was never about “them” at all. It was about us. It was our psychological security blanket, our best evidence that we were “all-in” in this war, the thing that proved to us that we were fierce enough to win.

Larison agrees:

Because of the bias in our debates in favor of hard-line policies, preventive war and torture not only become acceptable “options” worth considering, but they have often been treated as possessing the quality–seriousness–that they most lack. The belief that a government is entitled to invade a foreign country and destroy its government on the off chance that the latter might one day pose a threat is an outstanding example of something that is morally unserious. That is, it reveals the absence or the rejection of careful moral reasoning. Likewise, believing that a government should ever be allowed to torture people is the opposite of what comes from serious moral reflection.

Update from a reader:

Thank you for your superlative torture coverage. I am a writing to let you know of a revealing exchange I had recently on National Review Online. In reply to an article yesterday by David French accusing the torture report of being a “partisan mess,” and insisting on the usefulness of torture, I wrote the following:

If torture works, we want to be sure it works in the long run, not just the short run. I worry that even if via torture we foil a particular bomb plot in the short run, in the long run we will have just succeeded in making many more bombers, since the terrorists will successfully use the fact of American torture to recruit new terrorists.

One reply might be: so we should torture in secret. But that implies that everyone we torture must never tell about it. And the only way to guarantee THAT is to silence those we torture forever, by killing them or imprisoning them for life without trial. Is that where we really want to go as a country?

In reply, “Nightscribe” wrote:

I realize this is a waste of my time, but, the Republicans and I do NOT think interrogation/torture (if you like that word) is a recruitment tool for Islamic terrorists! It’s the WEAKNESS we show the world that we are willing to throw our military and their tactics under the bus for feeding them Ensure! For God Sake! Wake up!

And who gives a flying F*** if they tell anybody about it? We’re trading them off for deserters by the handful! They’re no doubt laughing so hard they can barely keep the blade straight on the next journalist’s neck!

I only hope the next torture tactic we use is eyeball with a grapefruit spoon! With VIDEO!

The rest of the comments contain many equally disturbing and deranged “hurray for torture!” claims. One common argument that crops up is the following: (i) We are civilized; (ii) our enemies are not; so (iii) we should torture them.

Do such people really not see that (iii) refutes (i)?

The Torture Report Blowback

So far, it consists mostly of tweets:

One day after the release of the report, massive riots and violent attacks on American installations abroad have yet to materialize.

However, the less immediate fear that the Senate report could provide recruiters from jihadist groups, including the Islamic State, with additional propaganda material is being realized. On Wednesday, the SITE Intelligence Group, which monitors Islamic extremist activity online, collected a series of tweets from apparent jihadist supporters and sympathizers who sought to frame the torture report as proof that Americans are waging a global war against Islam. SITE also noted jihadist calls for retributive attacks against specific targets.

Erica Chenoweth can find “no real systematic evidence to suggest that revelations of brutality lead to more violence”:

There is considerable evidence, however, that actual brutality (i.e. human rights violations, military invasions, and other forms of state violence during occupations) is associated with subsequent increases in terrorist attacks. Many people have referred to this effect in Iraq and Afghanistan—cases where foreign invasions and human rights violations clearly exacerbated rather than reduced violence. But plenty more scholarly studies indicate that states that rely on violence (especially indiscriminate and/or extrajudicial violence) to combat terrorism almost always end up prolonging terrorist campaigns rather than rooting them out.

Research by James Piazza and James Igoe Walsh show that states that violate physical integrity rights experience higher levels of subsequent terror attacks. Seung-Whan Choi finds a similar effect with regard to civil rights practices in general. Laura Dugan and I find that in the Israeli case, from 1987-2004 indiscriminate repression generally increased Palestinian violence, whereas more conciliatory counterterrorism measures (such as offers of negotiation or even public admissions of government abuses of Palestinians) tended to reduce subsequent violent incidents. And several others have shown that while British military strategies in Northern Ireland generally increased dissident violence, negotiations effectively ended it. Still other studies convincingly argue that criminal justice measures against those who have actually committed criminal acts are perfectly adequate in combating and deterring terror attacks.

In other words, brutal state strategies to counter “terrorism” are usually unnecessary – and they are more likely to backfire than to succeed.

How Do Americans Really Feel About Torture?

Paul Gronke, Darius Rejali, and Peter Miller challenge the conventional wisdom:

Our analysis, which is summarized in our 2010 paper, is that the American political and media elite badly overestimated public support for torture, especially in the early years of the war on terror and after the publicized events at Abu Ghraib. In this piece, we argued that the political and media elite came to false consensus. This is a coping mechanism long known to psychologists whereby we project our views onto others. We developed unique survey items that clearly showed widespread projection effects regarding torture, especially among those who were most supportive of these techniques.

Brittany Lyte is correct that public support has trended upwards, albeit slowly, since 2004, but those data are pretty steady since 2010. … Furthermore, when Americans are asked about specific techniques that Senator John McCain says have “dubious efficacy” and “risk our national honor,” public support is far lower. A table from our 2010 paper, reproduced below, shows that 81% oppose electric shock, 58-81% oppose waterboarding, 84-89% oppose sexual humiliation, etc.

Would You Report Your Rape? Ctd

Several readers open up:

You didn’t ask for answers to your question, but I’ll give you one, since McArdle’s doesn’t really do that. You can try to relate, but you can’t put yourself into the mind of someone who has been traumatized by sexual assault. I often reflect on why I didn’t report being raped by two men 15 years ago and what I would do differently if it happened today. I’ve thought a lot about this recently, as the story told in Rolling Stone bore some striking resemblances to my own. There are many reasons why I didn’t report my rape:

I just wanted it to go away, to forget it, to not talk about it. I felt ashamed, I blamed myself. While I was in shock from the trauma I had experienced and talking myself out of telling anyone outside my close circle of friends, those same friends helped to reinforce my decision. They reminded me that I had been drinking the night before and that I had kissed one of the men, willingly, earlier in the evening. These things were true and I would have to explain them to cops, lawyers, judges, my family, possibly my employer and I would be judged by them.

One comment from a friend that day haunts me still. She said, “You can’t go to the cops, T is on probation and could go back to prison”. It haunts me because it made perfect sense at the time, in the mental state I was in, I didn’t want to be responsible for someone going to prison. I was already blaming myself for their crime and its consequences.

Couldn’t this kind of reaction also help explain why a person’s memory of an assault could become warped over time? Just as forgetting key details is said to be the result of a coping mechanism, so could exaggerating details as a way to overcome feelings of guilt and shame. You were scratching your head over this yesterday, so it’s one possible explanation.

I’d like to think that if faced with the same decision today, I would be stronger, that I would “be the girl reporting it, sitting on a witness stand and pointing a finger”, that I would know that what mattered was what they did to me against my will and not what I did to deserve it – because I didn’t deserve it, and no one deserves to be violated in that way.

It’s been very difficult to read your blog lately, and I think that’s okay. Some of your posts on feminism and the Rolling Stone story have weighed on me in a way that those on other topics in which we disagree do not. Ultimately I appreciate your perspective, even as I dissent, because it forces me to check my biases, especially the ones that I know are emotionally driven and (hopefully) it helps me see with a bit more clarity.

Another reader:

I wrote once before (in the context of race and criminality) about being sexually assaulted by a man who was later convicted on multiple counts and sentenced to a long prison term. What I didn’t mention was the attitude of the police when I first reported it. They were extremely skeptical that I’d actually been attacked in my own apartment at 3 a.m. They asked if I was in a relationship, and I said I’d recently ended one but was still friends with my ex – whereupon they tried to convince me that he (the least violent of humans) was the man who’d “showed up” in my bed, and therefore it couldn’t be rape, so it really wasn’t a matter for the police.

It was only months later, when the pattern of a serial rapist became blindingly clear (with a dozen victims in my area) that they finally took me seriously. If being raped by a stranger at knifepoint can be spun away by police, think how they might treat an eighteen year-old who was drunk when she was raped by her date. If police believe you when you report your car stolen, shouldn’t they extend the same benefit of the doubt to a woman who reports a rape? Her claim may or may not hold up under investigation, as with any reported crime, but that’s no reason to assume a woman is lying or exaggerating. Yet all too often police do.

Another:

I completely agree with Megan McArdle’s comments: I have never been sexually assaulted, but I find it 100 percent easy to believe that a victim of a traumatic sexual encounter (even one that might not rise to the level of rape) would not report it or report a somewhat confused story with lots of second-guessing herself.

At the wedding of some friends several years ago, I had the surreal experience of being weirdly groped by a married friend of mine while we were in the middle of a conversation with another friend: the three of us were talking, and friend A kept running his hands up and down my thigh (I was on a barstool) and I was just drunk enough and just confused enough by the weirdness of what was happening that all I did was push his hands away each time (but he kept coming back!) and friend B didn’t do or say anything.

In my retelling of it to a friend who knew all the parties, I kept second-guessing myself: why would anyone do that?? He seems like such a normal guy! Maybe I was imagining it? Maybe it wasn’t as bad as it seemed? Maybe I’m making too much of this super weird situation. Especially when you’re a little buzzed, or tired, or whatever, I can completely understand not wanting to subject your brain and psyche – which are already confused and traumatized enough – to the skeptical questioning of some cop or campus security who might just see some drunk, slutty girl who’s angry at some guy.

From “Duck” To “Babe”

Jen Doll offers a history of terms of endearment:

Babe and baby as used to describe a romantic partner (rather than a small child or immature person; those usages began in the 1400s and 1500s) can be traced to usage that began in the 19th and 20th centuries in America. Initially, the words were simply used as a form of address (men were calling each other baby in 1835, sans any romantic connotations; in the 1996 movie Swingers, Vince Vaughn’s character employs the word for just about everybody).

The Oxford English Dictionary gives the first romantic use of babe as 1911, exampled by the Rodgers and Hart lyrics, “Oh, ma babe, waltz with me, kid. Gee, you’ve got me off ma lid.” In 1684, there’s an isolated use of baby by Aphra Behn: “Philander, who is not able to support the thought that any thing should afflict his lovely Baby, takes care from hour to hour to satisfie her tender doubting heart,” but the word doesn’t pop up again as a romantic descriptor until the 1860s: “Dear, dear, dear Baby, how often, how incessantly I think of you,” writes General H. M. Naglee. Baby is also used around that time to refer to “attractive young women,” and babe follows in that role in 1915, though it takes until 1973 for babe to apply to a man: “He’s a real babe … Mr. America!”

Before those two little b-words, though, came handfuls of nicknames you might apply to your lover, including cinnamon (1405), honeysop (about 1513), heartikin (1530), ding-ding (1564), pug (1580), sweetikin (1596), duck (1600), sucket (1605), flitter-mouse (1612), nug (1699), treat (1825), hon (1906), sugar (1930), and lamb-chop (1962). According to Katherine Connor Martin, head of U.S. dictionaries at Oxford University Press, “Really common endearments involved sweetness, sugar, and animals and birds. This baby concept is not something that has a long history. We can thank American English for innovating this particular strand.