Author: Andrew Sullivan

The Way We Lie Now

Clancy Martin praises Dallas G. Denery’s The Devil Wins for being the first systematic history of Western thought about lying, noting that one of the book’s more intriguing arguments is that “our Western understanding of deception has undergone a radical change from Augustine’s time to Rousseau’s”:

For Augustine, lying is always wrong and is an expression of our fallen state; for Rousseau, “the occasional lie” can be justified because we have been forced into deception by our decadent society. “If there is a before and an after in the history of lying, then Rousseau’s Discourses may well mark the moment when the one becomes the other,” Denery writes. “With Rousseau, deception and lying become natural problems, problems with natural causes and, hopefully, natural solutions.”

Indeed, Rousseau proposes some solutions in Émile, his treatise on the education of children, when he insists that—contrary to the notions of his own day, but in agreement with psychological research in the 21st century—most children lie because they are coerced into doing so by their own parents. I have called these “broken-cookie-jar lies”: What kind of deceptive behavior is a parent engaging in when he or she asks a young child, caught with a cookie in hand and a broken jar on the floor: “Now, who is responsible for that?”

The Most Quoted Experts

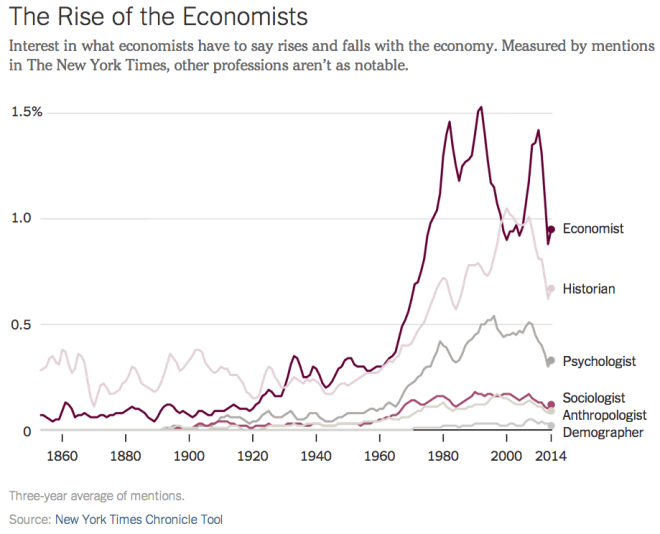

Justin Wolfers charts the recent dominance of economists:

There’s an old Bob Dylan song that goes “there’s no success like failure,” and it’s a lesson that’s been central to the rise of the economics profession. Each economic calamity since the Great Depression — stagflation in the 1970s, the double-dip recession in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the 1991 downturn — has served to boost the stock of economists. The long Clinton boom that pushed unemployment down to 3.8 percent was good news for nearly all Americans, except economists, who saw their prominence plummet. Fortunately, the last financial crisis fixed that.

Today, the profession is so ubiquitous that if you are running a government agency, a think tank, a media outlet or a major corporation, and don’t have your own pet economist on the payroll, you’re the exception.

The Expiration Date On That URL

Jill Lepore discovers that the “average life of a Web page is about a hundred days”:

No one believes any longer, if anyone ever did, that “if it’s on the Web it must be true,” but a lot of people do believe that if it’s on the Web it will stay on the Web. Chances are, though, that it actually won’t.

In 2006, David Cameron gave a speech in which he said that Google was democratizing the world, because “making more information available to more people” was providing “the power for anyone to hold to account those who in the past might have had a monopoly of power.” Seven years later, Britain’s Conservative Party scrubbed from its Web site ten years’ worth of Tory speeches, including that one. Last year, BuzzFeed deleted more than four thousand of its staff writers’ early posts, apparently because, as time passed, they looked stupider and stupider. Social media, public records, junk: in the end, everything goes.

Which is why the Wayback Machine exists:

The Wayback Machine is a Web archive, a collection of old Web pages; it is, in fact, the Web archive. There are others, but the Wayback Machine is so much bigger than all of them that it’s very nearly true that if it’s not in the Wayback Machine it doesn’t exist.

The Wayback Machine is a robot. It crawls across the Internet, in the manner of Eric Carle’s very hungry caterpillar, attempting to make a copy of every Web page it can find every two months, though that rate varies. (It first crawled over this magazine’s home page, newyorker.com, in November, 1998, and since then has crawled the site nearly seven thousand times, lately at a rate of about six times a day.)

The Internet Archive is also stocked with Web pages that are chosen by librarians, specialists like Anatol Shmelev, collecting in subject areas, through a service called Archive It, at archive-it.org, which also allows individuals and institutions to build their own archives. (A copy of everything they save goes into the Wayback Machine, too.) And anyone who wants to can preserve a Web page, at any time, by going to archive.org/web, typing in a URL, and clicking “Save Page Now.”

What’s In A Political Slogan?

Election guru Larry Sabato finds that slogans are often “simplistic and manufactured, but the best ones fire up the troops and live on in history.” His unsolicited advice for Hillary and Jeb:

The last time she ran for president, then-Sen. Clinton used “The Strength and Experience to Bring Real Change.” That was workmanlike—and boring. At least for the ’16 Democratic contest, she’d be better off with “Let’s Make History Again” coupled with the Helen Reddy tune “I Am Woman.” Don’t forget, about 57 percent of Democratic presidential primary voters are women.

For the general election, if President Barack Obama continues his recent climb in the polls, Clinton might adopt “Keep a Good Thing Going” or—to drive Republicans nuts—she might steal the 1982 Ronald Reagan midterm mantra, “Stay the Course.” If Obama’s popularity nosedives again, Hillary might want to revamp Bill Clinton’s 1992 anthem from Fleetwood Mac: “Don’t Stop Thinking About the Nineties.”

As for Jeb, he might want to try out “Not My Brother’s Keeper”—at least subliminally. He truly needs to be more Jeb than Bush as he attempts to achieve a historically unprecedented family three-peat. The word “conservative” needs to be prominent, given that so many voters in the GOP base think he isn’t. Terms to be avoided at all costs: immigration, common, and core.

Rupert Myers recently looked at political slogans, running down the best and worst of American and British ones of the past few decades. One of the best? The Thatcher-era indictment, “Labour isn’t working”:

[In] 1979, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party turned to Saatchi & Saatchi for the campaign slogan and poster [seen above] widely regarded to be one of the finest examples of a successful political slogan. Punchy, operating on more than one level, this is a rare example of an attack ad which works. It’s short, it’s sharp, and it draws contrast between the choices facing the electorate. Imitated by the Republicans in 2012, the slogan “Obama isn’t working” was less successful, a reminder that slogans don’t just have to work as a standalone message, but be dressed for the political climate.

This Extraordinary Pope, Ctd

Wow. Transgender man writes to the Pope after getting rejected from his church. On Saturday, the Pope met with him. http://t.co/hb73WbsUwB

— Gabe Ortíz (@TUSK81) January 26, 2015

A reader puts it well:

It seems to me that this is pretty big Pope news; he had a private audience with a transgender man and his fiancee. It’s inconceivable that such a meeting would have occurred with either of the two previous Popes. Which is a pretty sad indictment of them, in that Jesus clearly would have had such a meeting.

Mental Health Break

Moving forward, backwards:

The Exaggerated Benefits Of Bilingualism

Maria Konnikova examines the research of Angela de Bruin:

De Bruin isn’t refuting the notion that there are advantages to being bilingual: some studies that she reviewed really did show an edge. But the advantage is neither global nor pervasive, as often reported.

Where learning another language does pay dividends:

One of the areas where the bilingual advantage appears to be most persistent isn’t related to a particular skill or task: it’s a general benefit that seems to help the aging brain. Adults who speak multiple languages seem to resist the effects of dementia far better than monolinguals do.

When Bialystok examined the records for a group of older adults who had been referred to a clinic in Toronto with memory or other cognitive complaints, she found that, of those who eventually developed dementia, the lifelong bilinguals showed symptoms more than four years later than the monolinguals. In a follow-up study, this time with a different set of patients who had developed Alzheimer’s, she and her colleagues found that, regardless of cognitive level, prior occupation, or education, bilinguals had been diagnosed 4.3 years later than monolinguals had. Bilingualism, in other words, seems to have a protective effect on cognitive decline. That would be consistent with a story of learning: we know that keeping cognitively nimble into old age is one of the best ways to protect yourself against dementia. (Hence the rise of the crossword puzzle.) When the brain keeps learning, as it seems to do for people who retain more than one language, it has more capacity to keep functioning at a higher level.

Why Berlin Meant Boys

In a review of Robert Beachy’s Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, Alex Ross ponders why the city proved a relatively hospitable place for a thriving gay subculture that emerged at the turn of the 20th century. One reason? A deep and abiding connection between Romanticism and German culture:

Close to the heart of the Romantic ethos was the idea that heroic individuals could attain the freedom to make their own laws, in defiance of society. Literary figures pursued a cult of friendship that bordered on the homoerotic, although most of the time the fervid talk of embraces and kisses remained just talk.

But the poet August von Platen’s paeans to soldiers and gondoliers had a more specific import:

“Youth, come! Walk with me, and arm in arm / Lay your dark cheek on your / Bosom friend’s blond head!” Platen’s leanings attracted an unwelcome spotlight in 1829, when the acidly silver-tongued poet Heinrich Heine … satirized his rival as a womanly man, a lover of “passive, Pythagorean character,” referring to the freed slave Pythagoras, one of Nero’s male favorites. Heine’s tone is merrily vicious, but he inserts one note of compassion: had Platen lived in Roman times, “it may be that he would have expressed these feelings more openly, and perhaps have passed for a true poet.” In other words, repression had stifled Platen’s sexuality and, thus, his creativity.

Gay urges welled up across Europe during the Romantic era; France, in particular, became a haven, since statutes forbidding sodomy had disappeared from its books during the Revolutionary period, reflecting a distaste for law based on religious belief. The Germans, though, were singularly ready to utter the unspeakable.

In an interview about his book, Beachy sizes up just how remarkable such an outpost of gay culture was:

I think there probably had never been anything like this before and there was no culture as open again until the 1970s. So it’s really not until after Stonewall that one sees this sort of open expression of gay identity or homosexual identity – lesbian identity. … [T]here was this proliferation of publications that started almost immediately after the founding of the Weimar Republic and it continued really right down to 1933 until the Nazi seizure of power. So I think it’s really important to emphasize these publications because they were sort of the substrate, in a certain way, of this culture. They advertised all sorts of events, different kinds of venues and they also attracted advertisers who were really appealing to a gay and lesbian constituency, and that’s also really startling, I think.

“They Think, Therefore I Am”

Yatzchak Francus has discovered for himself that “having recovered from a brain injury is vastly different from having recovered from any other injury”:

No one thinks that a broken leg or a kidney stone or pneumonia fundamentally changes the essence of who you are. But when you’ve had a brain injury, people don’t believe that you are quite the same, although no one will actually say so. Perhaps it is the expression of a universal personal terror. The brain is who we are in the most fundamental sense. We are what we think, and we think with our brain. Not for nothing does Descartes’ summation endure.

The perceptions of my injury endure as well.

Although I have been fully back to normal for close to eight months, “How are you feeling?” continues to supplant “Hello” as the greeting of choice. Sometimes, it seems I hear the question at 15-minute intervals, as I did in the hospital. I half-expect the rest of the ICU script to follow: “Can you smile for me? Can you stick out your tongue? Can you hold up your arms up as if you’re holding a pizza box? Can you tell me what month it is?” When I decline a glass of wine at a holiday party, my host exclaims, “Of course, you have restrictions.” When my parents phoned a few minutes before Yom Kippur because I had forgotten to call them, I could hear the barely-suppressed panic in their voices, their improbable fear of a persistent vegetative state overwhelming the prosaic reality that the day had simply gotten away from me.