Matt O’Brien describes yesterday’s events:

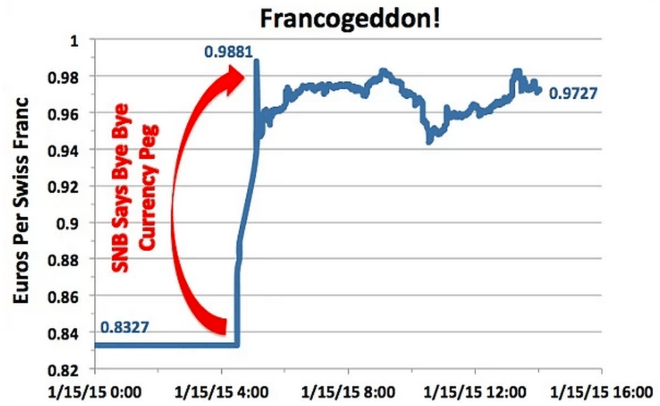

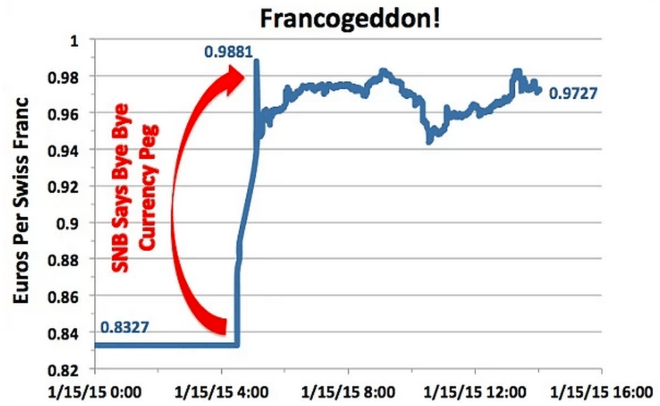

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) shocked markets on Thursday by announcing that it would no longer hold the value of the Swiss franc down at 1.2 per euro, although it would lower interest rates from -0.25 to -0.75 percent. Mayhem ensued. The Swiss franc immediately shot up as much as 39 percent against the euro, before settling at “only” up 17 percent on the day. This is basically the biggest single-day move for a rich country’s currency, as economist David Zervos points out, in the last 40 years. And it’s sent Switzerland’s stock market down 10 percent, as its suddenly more expensive currency will cripple its exporters by making their goods more expensive abroad.

Neil Irwin explains how, amid the euro crisis of 2011, if “you were a company or rich person in a country like Greece or Italy or even France or Germany, fearful that the euro could go kablooey and your local banks with it, you were sorely tempted to catch a flight to Zurich or Geneva and deposit your money in a Swiss bank”:

All those people looking to park money in Switzerland, a country of only 8 million people, created incredible upward pressure on the Swiss franc. From the start of 2010 to mid-2011, the value of the franc rose 44 percent against the euro.

Think about that for a minute. It would be as if dollars in the state of Virginia (with a population similar to Switzerland) suddenly were worth 44 percent more than the dollars used in the rest of the country. Virginians would be wealthier, but it would be a catastrophe for businesses in the state. Suddenly their costs would be 44 percent higher, effectively, than that of competitors in other states. Tourism would dry up; why go to a Virginia beach when it is 44 percent more expensive than a North Carolina beach?

Jordan Weissmann reviews the same history:

When the euro crises went into full swing during 2011, panicking money men saw the franc as a safe haven and started buying it en masse, pushing up its exchange rate with the euro, and pushing some exporters into bankruptcy. Sensing an emergency, the Swiss National Bank declared that it would start buying euros in “unlimited quantities” to keep the franc’s value down. Thus, we got the cap.

So what changed? Buying unlimited quantities of euros is about to get expensive. The European Central Bank is about to begin a round of quantitative easing to revive the region’s economy—which, for all intents and purposes, means it will be printing lots of euros, which Switzerland would have to purchase in bulk to maintain its exchange rate. That’s just not sustainable. So, instead, it’s bidding goodbye to the cap, and riding out the nasty economic consequences.

In his column today, Krugman argues that “the Swiss just made a big mistake”:

But frankly — francly? — the fate of Switzerland isn’t the important issue. What’s important, instead, is the demonstration of just how hard it is to fight the deflationary forces that are now afflicting much of the world — not just Europe and Japan, but quite possibly China too. And while America has had a pretty good run the past few quarters, it would be foolish to assume that we’re immune.

Dean Baker disagrees that Switzerland made a mistake:

Switzerland did not see the same sort of downturn as the rest of the OECD in 2008. Furthermore, it has fully recovered from its downturn with a GDP that is 8 percent above its pre-recession level and an unemployment rate of 3.5 percent.

In this context, it is actually doing what we should want Switzerland to do as a good world citizen. By allowing its currency to rise, it will make its goods and services less competitive internationally. This means it will import more from its trading partners and export less, effectively providing them with an economic boost. This is what we should want to see. The countries that are at or near full employment should be running larger trade deficits or smaller surpluses.

However, Scott Sumner sees Switzerland’s actions as monumentally stupid:

I sometimes receive back channel communication from very-well informed people in Europe. Believe me, just as with the earlier nonsense in Sweden, there is no “rational explanation.” People are appalled.

And Mark Gilbert worries about future financial surprises:

While victims of the turmoil ponder whether Swiss policy makers are irresponsible or just incompetent, the scale of the damage is a timely reminder that contagion is always unpredictable, that markets always overshoot, and that traders, when they smell profit, can outgun central banks.